A negative limit is a boundary or impasse that cannot be traversed. It is a line that in all truth and honesty we do not want to cross. This term is in common parlance among feminists. It is when we reach this negative limit in our experience that “blindfolds are removed,” sometimes gradually but more often dramatically or tragically. When I was a young single adult sitting in a crowded Memphis auditorium to hear a speaker my church had recommended, my negative limit was reached when the speaker, Bill Gothard, instructed us as follows: “Wives are to submit to their husbands—even if they are beaten to a bloody pulp—in the hope that their husband might be won to Christ.” It was as if I ran into a brick wall or impasse and slowly had to rethink the nature of the God I was serving, the veracity of the Bible I loved, and the commitment to be a Christian. The abuse and misuse of the book of Ephesians, specifically Ephesians 5, by the speaker tore the blindfolds from my eyes.

Each of the three women highlighted in this chapter—Sojourner Truth, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton—had blindfolds removed, which resulted in their commitment to and passion for the freedom of slaves and the vote for all people. The purpose of this chapter is to examine the intersection of the lives of these three extraordinary women, who each contributed in distinctive ways to the fight for equal vote, voice, and possibilities for women. My research is driven by the quest to see how they found commonalities amid the differences of their lives. This chapter is built on the assumption that all three women had their “blindfolds removed” to see the savagery of the treatment of slaves and the diabolical bondage of women as well as the possibilities of the right to freedom and the right to enfranchisement, which includes the right to vote. Is there something in their common vision that would enlighten those of us today who continue the struggle against the exploitation of others? What was the connection among these three women? What were other commonalities that drew such dissimilar women together? How did they navigate differences?

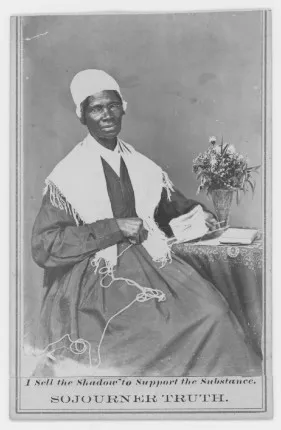

Original carte de visite (calling card) of Sojourner Truth (Brady’s National Photographic Portrait Galleries, NYC and Wash., DC), ca.1870s.

Original cabinet card, Harriet Beecher Stowe, printed by Rodgers.

Original signed carte de visite, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, 1902.

Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth, née Isabella Baumfree, knew nothing but slavery as a child. She was an infant when her brother, age five, and her sister, three, were sold away from her parents, leaving them inconsolable. Among Isabella’s earliest memories was the new house of her master, Charles Ardinburgh, which he had built for a hotel. “A cellar, under this hotel, was assigned to his slaves, as their sleeping apartment, —all the slaves he possessed, . . . sleeping . . . in the same room. She carries in her mind, to this day, a vivid picture of this dismal chamber,” with loose boards on the floor over the uneven earth, which was often muddy, with splashing water and noxious vapors. The slaves slept body to body across the damp floor, lying on a little straw and a blanket, as if they were horses. Servitude in degradation was the life she knew. In her Book ofLife, however, she comments on the dispelling of “the mists of ignorance” and the removal of the shackles of body and spirit:

As the divine aurora of a broader culture dispelled the mists of ignorance, love, the most precious gift of God to mortals, permeated her soul, and her too-long-suppressed affections gushed from the sealed fountains as the waters of an obstructed river, to make new channels, bursts its embankments and rushes on its headlong course, powerful for weal or woe. Sojourner, robbed of her own offspring, adopted her race.

I am suggesting that her blindfolds of bondage were removed to see “the divine aurora” of a broader culture after the mists of ignorance imposed on her by a lack of freedom began to evaporate over time. Her adoption of her race is seen in her tireless efforts to improve the sanitary conditions for the freed slaves who gathered in Washington. She assisted the National Freedman’s Relief Office, Freedman’s Village, Freedman’s Hospital, and orphanages for freed children to compensate for the lack of foresight by the US government. Who had thought ahead about how the freed slaves would exist, live, and support themselves when they left plantations, masters, and overseers? Sojourner Truth instigated a petition to both the House and Senate to address these issues, whereby the freed slaves could be given land that they so rightfully deserved in order to support themselves. After all, hadn’t their unpaid labor boosted the economy of the nation? This is an example of perspicacity, which, among other things, can be described as sagacity and sharp-sightedness.

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Beecher Stowe was raised as a minister’s daughter in a home and church where she heard her father, Lyman Beecher, deliver graphic sermons on the evil of slave trading. Lyman Beecher came from a long line of ministers. Harriet’s pious mother died when she was four; thus, Harriet was not unfamiliar with hardship. Her father was called to Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati in 1832, when Lane Seminary was a hotbed of abolition. At the time the Beecher family moved there, Theodore Weld was a student and radical abolitionist at Lane. Harriet, like her sister Catharine, was more committed to education than the issue of slavery.

In 1833, Harriet made a trip from Cincinnati to Kentucky with a teacher named Miss Dutton. It was there that Harriet came in contact with slaves of the South. In the biography written by Harriet’s son, Charles Edward Stowe commented that Miss Dutton realized later that scene after scene in Uncle Tom’s Cabin came from that visit to Kentucky.

While in Cincinnati, Harriet witnessed proslavery mobs pull down houses of respectable and law-abiding blacks. She knew the office of Mr. J. G. Birney, editor of The Philanthropist, had been ransacked and demolished by those angered by his liberation of his slaves in Alabama. She had a desire to do something. Meanwhile, her husband, Professor Stowe...