![]()

Introduction

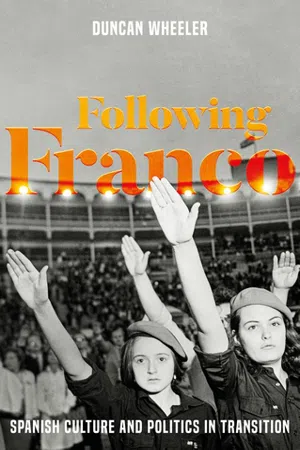

On returning to the United Kingdom in 1962 to complete an undergraduate degree in Spanish following her year abroad, Lucia Graves – the daughter of the poet Robert, raised in Mallorca – recalls Conchita, a woman running a dressmaking school, who was obsessed with listening to radio agony-aunt Elena Francis, and wonders: ‘Could all this world of Madrid be encompassed in an Oxford translation class?’1 The answer was clearly no. If, as Joke Hermes contends, ‘[p]opular cultural texts and practices are important because they provide much of the wool from which the social tapestry is knit’,2 then the principal aim of this part is to show the importance of celebrity to the cultural politics of a period when the ‘distinction between an ascetic Spain and an indulgent West rested on a distinction of consumer values that, if they [had] once existed, no longer did’.3

Over the course of the 1960s, the combined sales of women’s magazines Lecturas, Semana, ¡Hola! and Diez minutos eclipsed the rest of the market combined.4 Spaniards were not avid newspaper readers: the first serious market research suggested the country had 107 newspapers, but that only 5 per cent had a circulation of over 100,000.5 The pro-monarchist ABC sold best (192,000 copies), a far cry from the 5 million copies of the Daily Mirror sold in the UK;6 the combined sales of newspapers in Spain in 1967 were around 2.5 million.7 The interpellation of (un)willing subjects in a culture of non-inquisitiveness was evidently one of Francoism’s chief political triumphs, but work remains to be done on critically interrogating the information available to everyday Spaniards alongside a more nuanced understanding of how this both shaped and reflected their interests. During the nascent democratic period, a number of canonical cultural texts – most eminently the documentary film Canciones para después de una guerra (Songs for after a War) (Basilio Martín Patino, 1976) and Carmen Martín Gaite’s 1978 novel El cuarto de atrás (The Back Room) – resurrected the popular culture ostensibly patented by the Franco regime in the 1940s and 1950s. As Stephanie Sieburth notes, ‘El cuarto de atrás teaches us that the effects of role-play through mass-culture can be positive, negative, or both at once.’8

This part has been designed as an academic counterpart to such creative enterprises. In the first chapter, I employ two case-studies – the bullfighter ‘El Cordobés’ and pop singer Raphael – to explore the gender- and class-infected discourses that emerged around celebrity culture in a period described by Nigel Townson as the ‘transition to the Transition’.9 I will analyse how and why these figures provided evidence for the oppositional left to understand mass culture as the opium of the masses, a surreptitious form of depoliticisation. A dogmatic desire to denigrate rather than engage with celebrity culture nevertheless proved counter-productive for their progressive ideological agenda. Politics and celebrity culture are frequently construed as antithetical, but they share the common trait of being ubiquitous and invisible in late-twentieth-century Spain, everywhere and nowhere at the same time. Chapter 2 critically interrogates the extent to which remodelled formations of power and influence were forged and contested though a generational shift as embodied by a series of aristocratic figures from the royal and Franco families. The third and final chapter hones in on the leading lights of the 1980s Spanish media-scape – Isabel Preysler, Isabel Pantoja and Julio Iglesias – to suggest that Spain’s reputed jump from pre- to postmodernity was not as clear-cut and absolute as it often assumed to be, and that this is inextricably linked with the political and diplomatic power celebrities continued to wield at home and abroad.

![]()

Modern celebrity culture predates Hollywood and the Internet. The public began taking a strong interest in a large number of living authors, artists, performers, scientists and politicians in the eighteenth century.1 In Spain, celebrities first arose when bullfighting ceased being an exclusively aristocratic practice to become a form of mass popular entertainment. As Tara Zanardi remarks, ‘[l]ike the actors of the British stage, bullfighters in part acquired their new stature from their performance of aristocracy’.2 Celebrities simultaneously reflect and transform the societies from which they emerge.

In what follows, I chart how and why the two most important male celebrities of 1960s Spain bear testament to Justin Crumbaugh’s claim that Manuel Fraga, the incoming Minister of Tourism and Information (1962–9), advocated ‘a conscious re-politicization of society through the symbolic channels made available by Spain’s emergent information age’.3 Combining tradition and modernity in terms of biography, public persona and performance styles, Manuel Benítez ‘El Cordobés’ and Raphael were simultaneously exploited and exploitative in their attempts to present a benign image of a dictatorial regime for domestic and international consumption. The humble origin of many Andalusian stars was a long-standing celebrity trope, but a saccharine ‘rags to riches’ narrative became ubiquitous at a time when, with the exception of Japan, Spain had the fastest growing economy in the world.4 The bullfighter and the melodic pop singer constituted ego-ideals for millions of Spaniards moving from the country to the city, as aspiration replaced austerity as the national ideal. In an increasingly urban consumer-based society, celebrity media-reports were fixated by jet-set lifestyles: frequent plane trips, stays in Hilton hotels, rides around different cities in convertible sports cars, etc.

As Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre wrote in their international best-seller, a ‘factional’ novel titled Or I’ll Dress You in Mourning: The Story of El Cordobés and the New Spain He Stands For, ‘love of art may drive a man to a bullring’s ticket window, but it is hunger that drives him onto its sands’.5 Born in 1936, Benítez suffered the after-effects of the Civil War first-hand: his father died in the prison into which he had been thrown for his Republican sympathies. Raised in social care, the orphaned child did whatever was necessary to improve his fortunes: teetering on the edge of starvation and criminality, he made a name for himself in small towns and villages by taking on bulls in ramshackle and frequently lethal festivities from a young age. On 21 February 1961, Pipo – El Cordobés’s ruthless and ambitious manager – organised the first bullfight to be held in Franco’s principal residence, the Pardo, as part of a charity event organised by the Caudillo’s wife, Carmen Polo, to raise funds to build housing for the poor.6 El Cordobés would never have succeeded – or, at least not to such a great extent – in an age prior to the arrival of mass media and the package holiday. To the consternation of purists, he was more a consummate celebrity entertainer than an orthodox matador. His crowd-pleasing antics included a series of well-rehearsed tricks: chief in his arsenal was a gymnastic display of bravery in which he ostensibly allowed himself to be dominated by bulls that frequently tossed him high in the air. Performances outside the ring were similarly stage-managed. On 4 May 1965 he was flown on his private light aircraft to Tenerife;7 greeted at the airport by fans and reporters, he then opened a renovated cigarette factory, whose owners sponsored the bullfight that brought him to the Canary Islands. Curro Romero, a classical bullfighter, has complained of sensationalism, ‘when many of us came from the same place, but didn’t have that kind of marketing’.8 Benítez’s appeal was boosted by fabled tales of generosity; having once been denied medical treatment after a serious goring for not being a union member, he was reputed to have used his position as the world’s foremost matador to insist that all injuries be treated.9 The legend was amplified in hagiographic biographies10 and Aprendiendo a morir (Learning to Die) (Pedro Lazaga, 1962), a saccharine cinematic star vehicle in which Benítez played himself;11 the star reputedly did not read the script as he had yet to learn to read.12

Television enabled more Spaniards to witness the national fiesta than ever before, whilst mass tourism transformed it into an increasingly lucrative industry. In 1962, the then Director-General of Tourism, Don Manuel de Urzáiz, claimed that 70 per cent of requests for information received by his office from abroad related to bullfighting.13 The Mayor of Fuengirola justified using public funds to subsidise the construction of a bullring that same year by a private concern with recourse to the argument that it would attract tourists to the municipality on the Costa del Sol.14 In 1963, there were 360,000 television sets in Spain; this figure had risen to 1,250,000 in 1965 and to over 3 million in 1968.15 Whenever a televised bullfight was announced in advance, factory workers requested (and usually received) permission to start work two hours earlier to be able to finish in time to watch the event.16 Pepín Toboso, owner of the Galerías Preciados chain, complained that revenue plummeted, and unsuccessfully petitioned the State to delay the transmission of Benítez’s bullfights until after his department stores had closed.17

According to Kenneth Tynan, El Cordobés was ‘arguably the highest-paid individual performer in European history’:

Following the breakthrough success of the Beatles, the first holiday manager Brian Epstein took was to Spain in 1964 to meet with Benítez. Epstein’s travelling companion, Peter Brown, recalls:

The project may not have materialised, but Epstein’s fascination with the taurine world did not end there. According to Nat Weiss, his American business partner: ‘Bullfighters were to Brian what the Beatles were to music fans. They were his idols.’20 Epstein indulged his fantasies by managing British bullfighter Henry Higgins and hanging a photo of El Cordobés in his London bathroom.21 The Beatles performed to a half-empty Las Ventas bullring in 1965 shortly after receiving their MBEs from Queen Elizabeth II. The connection between British pop aristocracy and El Cordobés would be revitalised in the 1980s when Tom Jones recorded ‘A boy from nowhere’, based on Benítez’s life, from the otherwise unsuccessful musical Matador, subsequently staged in London in the early 1990s.

Benítez was an idol not because he wanted to change society, but rather because he suggested it was possible for one to change position within the social hierarchy. Frank Evans, the son of a Conservative councillor, who would go on to become footballer George Best’s informal manager in Manchester and a matador in Spain, recalls tales told to him as a teenager in northern England by family friend Paco Montes: ‘El Cordobés lived the life. I wanted to be part of it but had absolutely no idea how to get there or what to do.’22 In El espontáneo (The Rash One) (Jorge Grau, 1964), for the film’s eponymous protagonist (a hotel bell-boy unfairly dismissed after being sexually molested by drunk foreign female guests) flicking through a magazine with glamorous images of Benítez is instrumental in his deciding to try his own luck in the ring. Harassment was treated here in a comic vein but it frequently had tragic real-life consequences when the ‘widesp...