![]()

1

The Gun That Shoots Twice

The seven-pounders are most excellent guns, as they are made to stand any amount of knocking about, and also to be mounted and dismounted in a very short space of time. They are much disliked by the natives of the country, who call them ‘them gun that shoot twice’ – referring to the explosion of the shells, which they consider distinctly unfair, taking place as it does so far away from the gun, and mostly unpleasantly close to themselves, when they are, as they fondly imagine, out of range.

Captain Alan Boisragon, Commandant

of Niger Coast Protectorate Force (1897)1

Along the Niger River since 1894 Alan Boisragon had seen scores of military ‘punitive expeditions’ in the bush, with warships, Maxim machine guns, rocket launchers and Martini-Henry rifles. In the passage above, he is describing the rifled muzzle-loading mounted carriage field gun, known as a ‘seven-pounder’ because of the weight of the shell that it fired (about 3.2 kilograms), in his popular account of the military attack on Ubini2 (Benin City) by Niger Coast Protectorate and Admiralty forces in February 1897. Boisragon does not record the number of casualties from the shelling of the city, of scores of surrounding towns and villages, of incessant firing of machine guns and rockets into the bush, during this 18-day attack. He does not take stock of the numbers of killed and wounded soldiers and displaced people in the many, many previous ‘expeditions’ and attacks, or reflect on the extent of death and injury in the many as yet unplanned expeditions of the coming months and years, as yet unnamed: Opobo, Qua, Aro, Cross River, Niger Rivers, Patani, Kano, ‘opening up new territories’, ‘journeying into the interior’, ‘pacifications’, exacting punishment for supposed offences against civilisation.

Undetained by any question of African deaths, this description in fact came from an autobiographical adventure story, in which Alan Boisragon told of his own escape in the face of attack, one of just two survivors of the earlier supposedly peaceful expedition to the City in January 1897, during which perhaps seven (or perhaps five) Englishmen were killed, and how he and his comrade had to walk through the jungle for five days before finally returning to safety and civilisation – ready to exact a brutal revenge on his ‘barbaric’ attackers and the heart of their ‘uncivilised’ power – the so-called city of blood.3

The Daily Mail and The Times led the newspaper coverage of this Boys’ Own yarn of ‘massacre’ and heroism and to which the February ‘punitive expedition’ was the necessary response. A year later, the War Office was issuing medals commending soldiers described as members of ‘the squadron sent to punish the King of Benin for the massacre of the political expedition’.

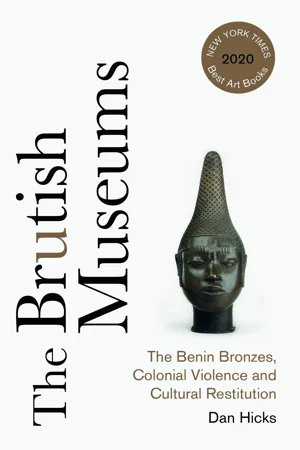

This is a book about that violent sacking by British troops of the City of Benin in February 1897. It rethinks the enduring effects of this destruction in Britain today, taking stock of its place in a wider military campaign of regime change, underscoring its status as the pivotal moment in the formation of Nigeria as a British protectorate and British colony, exposing how the many ‘punitive expeditions’ were never acts of retaliation, and trying to perceive the meaning and enduring effects of the public display of royal artworks and other sacred objects looted by marines and soldiers from the Royal Court now dispersed across more than 150 known museums and galleries, plus perhaps half as many again unknown public and private collections globally – from the Met in New York to the British Museum, from Toronto to Glasgow, from Berlin to Moscow, Los Angeles, Abu Dhabi, Lagos, Adelaide, Bristol and beyond. Some of these objects have a truly immense monetary value on the open market today, selling for millions of dollars.

Objects looted from the City of Benin are on display in an estimated 161 museums and galleries in Europe and North America. Let us begin with this question: What does it mean that, in scores of museums across the western world, a specially written museum interpretation board tells the visitor the story of the Benin Punitive Expedition?

One of the largest of these collections of violently stolen objects, trophies of this colonial victory, is the University of Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum – where I am Curator of World Archaeology. Are museums like the Pitt Rivers just neutral containers, custodians of a universal heritage, displaying a common global cultural patrimony to an international public of millions each year, celebrations of African creativity that radically lift up African art alongside European sculpture and painting as a universal heritage? The point of departure for this book is the idea that, for as long as they continue to display sacred and royal objects looted during colonial massacres, they will remain the very inverse of all this: hundreds of monuments to the violent propaganda of western superiority above African civilisations erected in the name of ‘race science’, littered across Europe and North America like war memorials to gain rather than to loss, devices for the construction of the Global South as backward, institutions complicit in a prolongation of extreme violence and cultural destruction, indexes of mass atrocity and iconoclasm and ongoing degradation, legacies of when the ideology of cultural evolution, which was an ideology of white supremacy, used the museum as a tool for the production of alterity: tools still operating, hiding in plain sight.

And so this is a book about sovereignty and violence, about how museums were co-opted into the nascent project of proto-fascism through the looting of African sovereignty, and about how museums can resist that racist legacy today. It is at the same time a kind of defence of the importance of anthropology museums, as places that decentre European culture, world-views and prejudices – but only if such museums transform themselves by facing up to the enduring presence of empire, including through acts of cultural restitution and reparations, and for the transformation of a central part of the purpose of these spaces into sites of conscience. It is therefore a book about a wider British reckoning with the brutishness of our Victorian colonial history, to which museums represent a unique index, and important spaces in which to make those pasts visible.

The Pitt Rivers Museum is not a national museum, but it is a brutish museum. Along with other anthropology museums, it allowed itself to become a vehicle for a militarist vision of white supremacy through the display of the loot of so-called ‘small wars’ in Africa. The purpose of this book is to change the course of these brutish museums, to redefine them as public spaces, sites of conscience, in which to face up to the ultraviolence of Britain’s colonial past in Africa, and its enduring nature, and in which to begin practical steps towards African cultural restitution.

* * *

Stand in the Court of the Pitt Rivers Museum and go up to the Lower Gallery. Walk with me to the east wall and stop in the still, dark space; the vast silent expanse of the museum is behind us and before us is a cabinet of sacred and royal objects, dimly lit, returning our gaze. Let us step before the glass ‘in order to soak up the fugitive breath that this event has left behind’.4

Hold your phone up against the plate glass of the triple vitrine. The silence and stillness are not natural conditions for the displaced objects on display here. They are the effect of a stilling, as when detention interrupts transit, and of a fracturing, as when a shrapnel shell explodes at its target, and of a silencing, as when a gun is silenced.

The Victorian wooden case is nine feet high. There are more than a hundred objects contained within: bronze and wooden heads, brass plaques, ceremonial swords, armlets and headgear, boxes and carved ivory tusks, one burned in the fire of the sacking. The title reads: ‘Court Art of Benin’, and then an interpretation panel states:

Benin is a kingdom in Nigeria, West Africa. It has been ruled by a succession of kings known as Obas since the fourteenth century. Benin is famous for its rich artistic traditions, especially in brass-casting. In January 1897 a small party of British officials and traders on its way to Benin was ambushed. In retaliation a British military force attacked the city and the Oba was exiled. Members of the expedition brought thousands of objects back to Britain. The Oba returned to the throne in 1914 and court life began again. The artists of Benin continue to make objects for the Oba and the court, and rituals and ceremonies are still performed. The objects displayed here were made between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries.

How little has changed over the decades since February 1899 when Charles Hercules Read and Ormonde Maddock Dalton, the Keeper and Senior Assistant respectively in the Department of British and Medieval Antiquities and Ethnography at the British Museum introduced their catalogue Antiquities from the City of Benin by telling the same story of ambush and retaliation – ‘objects obtained by the recent successful expedition sent to Benin to punish the natives of that city for a treacherous massacre of a peaceful English mission’5 – with the following note of explanation:

Captain Gallwey, of the East Lancashire Regiment, [was] sent on a political mission in 1892. Four years later a larger mission, under Consul Phillips, was attacked on its way up from the coast, and the majority of the party were massacred. This outrage led to the despatch of a military expedition, which destroyed Benin City, and made accessible to students of ethnography the interesting works of native art that form the subject of the following pages.6

The museum may operate to stabilize and reproduce certain narratives, and to repress and diminish others – but only ever provisionally. Insofar as the museum is not just a device for slowing down time, but also a weapon in its own right, then to what extent are its interventions with time like the brute force of field guns manned by Captain Boisragon’s African forces, carried through the jungle by men selected for their physical strength, a projection across time and space, where some kind of explosion is yet contained in each brass object within this vitrine, unfinished events from which the curator might feel safely out of range, having taken place so far away across time and space: another continent, another millennium? By intervening with time, decelerating memory, displaying loot, what kind of ordnance has the museum brought within its glass cases, caught between one shot and another, between the projection and the return? What do we see when a light is shone into these most hesitant, uncertain of spaces, unresolved and raw? What connections will be made when human time and space re-align and the thing is still here? Each stolen object is an unfinished event, its event-density grows with each passing hour. The Victorian soldiers and museum curators said these were ‘ju-ju’ fetishes whose power needed to be broken. Spend time in front of this case and the solid and the visible seem to soften, as when brass is cast, to blend with memory and with knowledge, at a tipping point. A new conjunction is coming about for museums and empire. What is this moment? How does loss come into view?

* * *

Objects from Benin’s Royal Court, burnt to the ground by British troops, are displayed in the ‘court’ and galleries of this Oxford museum. What kind of archive is this replica, this stagey performance in a windowless space today curated to enchant, a century and a half ago built to shape knowledge, to redraw the world? Anthropologists have a word for it: myth. And myths are temporal devices. Myth serves, as does music, as Claude Lévi-Strauss famously argued, to ‘immobilize the passage of time’, so ‘overcoming the antinomy of historical and elapsed time’. The technologies of the museum and the archive – the museum label, the zip-lock bag, the conservation lab – are analogous interventions. They are forms of notation: dal segno (‘go back to the mark’). Among the outcomes of these technologies are provisional and contingent stoppages in time, rendering fragments as objects, which are wrought as cadences. A form of secondary deposition emerges in the museum, like curtain calls.7 In 2017, Edward Weisband8 observed that various spectacular or dramaturgical political and symbolic forms, which he calls ‘the macabresque’, tended to accompany mass violence during the 20th century – a kind of sadistic, performative self-creation that emerges hand-in-hand with the inflicting of loss, the myth of the ‘primitive’ in violence extended across time: the weaponization of time itself.

Benin City lies on a high sandy plain to the north of the Niger Delta in Edo State, Nigeria, in an area of former tropical forest. Today, it is a city of 1.5 million people and the centre of a major precolonial kingdom of the Niger Delta, which once controlled the land and river systems that connected the African interior with the maritime world of the Bight of Benin and the Atlantic Ocean. The city first emerged during a period of urbanisation and state formation along the tropical belt of West Africa, some one thousand years ago, which saw the emergence of the great centres of Edo, Yoruba, and Akan pre-colonial states: Benin, Ife, Ilesa, Oyo, Kumasi, Begho – with Aja and Fon states and urban polities such as Dahomey emerging later, from the 16th century. The Kingdom of Benin has been ruled by an unbroken line of Obas (Kings) that began with Ewuare I who reigned from 1440 ce – a century before Queen Elizabeth I came to the English throne – and had its origins in the late Iron Age urban societies of the 10th or 11th century ce onwards: when he was crowned in 2016, the current Oba, Ewuare II, became the fortieth Oba in an unbroken line across eight centuries. The Kingdom grew in power and scope during its involvement in European and transatlantic trade from the 16th century, at first with Portuguese traders, and later British and French – central among which was the slave trade. By the 19th century, Benin City was a sacred monumental landscape of courthouses, compounds, and mausoleums, the centre of royal and religious power encompassed in an ancient network of ditched and banked earthwork enclosures, and with central repositories of thousands of unique artefacts that bore witness to the kingdom’s past – a kind of unseen city, a centre for changing forms of religious observance and royal power over centuries. The sacking of this city, more than twelve decades ago, involved the looting of more than ten thousand royal and sacred objects.

In the artificial, darkened secondary landscapes of this museum, let us understand this place not as some dazzling gathering of the flotsam...