![]()

ONE

A PREHISTORIC PRELUDE:

The Dwellers in the Cliffs

High above the valley floor stands the flat tableland. In later years the Spaniards called the river the Rio de los Mancos—the River of the Cripples; they termed the tableland Mesa Verde. Still later, Americans came, ran survey lines, and found that the tableland fell within the borders of what became Colorado. But that was centuries after the original mesa dwellers had vanished from the land.

The modern tourist, driving from Durango to Cortez on US 160, sees the mesa looming large to the left, rising 2,000 feet straight up from the floor of the valley. Twenty miles wide, it slopes backward fifteen miles to the south from the startling promontory. This flat tableland is cruelly severed by rugged canyons cut by eroding river water. On the mesa, and in its canyon walls, stands evidence of a civilization that had died long before any white person had climbed to the top of the tableland. No real knowledge or tradition passed from the cliff dwellers to their successors on the mesa; there is no historical link between the two civilizations. But in the remnants of the cliff dwellers we find much to ponder in casting up accounts of our own civilization.

Sometime in the unrecorded past, according to educated guesses, Homo sapiens crossed a land bridge that is now known as the Bering Strait and pushed down through the continents. The exact date of these migrations may never be known. Perhaps 15,000, perhaps 20,000 or more years ago, early humans found themselves in the New World. Nomadic, depending upon wild animals and natural foods for sustenance, the Paleo-Indians battled the elements and the terrain for their very existence. Some of them slowly changed their nomadic life and became agricultural people with fixed abodes.

The arrival of home-seeking Paleo-Indians in the Mesa Verde region probably coincided with the beginning of the Christian Era in the Old World. From that time on, for the next thirteen centuries, they occupied the area. These farmers passed through four more-or-less defined periods of advancement until, before they left the mesa, they would boast of a complex civilization.

The first era, called the Basketmaker Period, extended from approximately the year ad 1 to 450. As long as these people retained their undomiciled lives, they left little evidence for the archaeologist to use in reconstructing the patterns of their society. With the advent of fixed abodes arose the opportunity for the accumulation of artifacts that could later be unearthed and studied; long unused tools, household utensils, and weapons give us a picture of this culture. Thus the earliest mesa dwellers of whom we have knowledge date from the era when they shed their nomadic habits and began to take up farming.

These black-haired, brown-skinned hunters learned the techniques of cultivating corn and squash, beginning the march from wanderers to stay-at-homes, with new leisure to develop arts and crafts. Of course that march was slow. Most of these early people probably never lived in houses, but sought shelter when it was needed in natural caves. Nor did they know how to make pottery. Their name, Basketmakers, comes from their substitute for pottery—skillfully constructed, often decorated baskets. They designed baskets as containers for food and supplies; they wove baskets so tightly they could hold water and by dropping heated stones into them, they could use them for cooking food.

Without houses, without pottery, the Basketmakers were handicapped in comparison with later mesa dwellers. Probably their most serious deficiency was the lack of a good weapon. The bow and arrow had not yet made its appearance, and the first Basketmakers used, instead, the atlatl. This arm-extender, or spear-thrower, was a flattened, slender stick used to extend the reach of the arm and provide greater thrust in throwing a dart or a spear.

Although the warm summer months on the mesa provided a climate in which clothing was not needed, the winter weather was severe enough to make clothes essential for comfort. The Basketmakers depended upon animal skins and woven fur strips fashioned into robes for protection against the cold. They wove sandals from yucca fibers. The only other article of clothing was a string apron worn by the women. Obviously, the Basketmakers limited their wardrobes to essentials. Nevertheless, they were fond of jewelry and trinkets, and they fashioned bones, seeds, and stones into ornaments for their necks and ears.

The Basketmakers’ implements and tools ranged from wooden planting sticks to knives and scrapers, pipes and whistles. They used a metate, or grinding stone, to make flour of their corn. Their children were cradled in flexible reed boards with soft padding under the head, allowing the infants’ skulls to develop naturally without abnormal flattening.

What elements of religion these Basketmakers professed and practiced is not easily deduced. They buried tools and jewelry with the dead, perhaps for the use of the departed in an afterlife. Burials were usually made in floors of caves or crevices in rocks; often more than one body was placed in the same grave.

Such was the culture at the end of the first developmental period. These early people had made tremendous strides from their nomadic life, conquering the secrets of planting and cultivating, harvesting and storing crops. Now modifications of those improvements slowly began to appear. The culture evolved into something so different from what it had been that a new term is needed to describe it.

The term “Modified Basketmaker Period” identifies the second developmental era, from ad 450 to 750. The changes were not simultaneous, but gradually three new elements made the Basketmakers’ lives more complex. To the amazing improvements their ancestors had perfected, the Basketmakers added pottery, houses, and the bow and arrow.

The clay pottery that replaced the baskets probably was an invention borrowed from other tribes rather than indigenously developed. Even so, the mesa dwellers learned the new art slowly. Their first clumsy vessels were constructed of pure clay; the pots had little strength and less beauty. But the creators gradually added refinements: straw mixed with the clay, sand added for temper. The pots provided a startling change from the basket days. New foods were added to the diet, and new methods of water storage eased the struggle for existence against the hazards of nature.

For housing, the Modified Basketmakers developed the pithouse. They dug a hole several feet deep and from ten to twenty feet in diameter. Then, using logs as a framework for the portion above the ground, they covered the framework with interwoven reeds and grass and placed a layer of earth over this “lath” to form combination sidewalls and roof. A small opening in the center of the roof provided both a smokehole for the firepit and an entrance; they went in and out by ladder. A ventilating tunnel furnished air for the fire in the pit. They built some of their pithouses—probably the early ones—in caves, but gradually they abandoned those inaccessible sites for more expansive locations on the top of the mesa and in the valley floors. The new sites were relatively unprotected and suggest that the Modified Basketmakers lived without particular fear of their neighbors.

During these same years the bow and arrow replaced the atlatl. The mesa people probably borrowed the bow and arrow, like pottery, from others. With characteristics peculiarly attractive to the game hunter, the new weapon offered greater accuracy at longer ranges than the atlatl.

Pottery, pithouses, and the bow and arrow were the radical advances of the era, but there were others. Beans were brought into the area as a new crop, and previously unknown varieties of corn appeared. The people domesticated the turkey, perhaps not for meat but certainly for the string-cloth fashioned from feathers to be woven into robes.

Then about ad 750 another demarcation line was crossed: the Developmental Pueblo Period lasted until ad 1100. The word pueblo (Spanish for village or town) has been applied to the most significant change during the eighth and following centuries. The Basketmakers had constructed most of their pithouses as single family structures. They had grouped their dwellings into villages, and some ruins indicate long rows of flat-roofed houses. In the Developmental Pueblo Period, the people experimented with more complex multiple units, with walls of various materials, suggesting a pragmatic approach to an ancient housing problem. They erected these new apartment houses all over the top of Mesa Verde. Ruins of similar structures exist in an extended area of the Four Corners region, into Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico. Population expansion seems obvious, while the unprotected nature of the mesa-top dwellings suggests a period of tribal peace.

The first pueblos were rather crudely constructed of posts and adobe. By the end of the period, however, adobe had given way to masonry, increasingly well set. Some walls were now two stories high. And the kiva (a Hopi word used by archaeologists to describe the rooms that resemble the modern Pueblo ceremonial chamber) now began to resemble the standard Mesa Verde kiva. Circular, subterranean, some twelve to fourteen feet in diameter, seven or eight feet deep, with walls of dressed stone, the kiva was located in front of the living rooms. Masonry pillars supported the roof of logs and adobe. Like the earlier pithouses, the kiva’s only door was a small opening in the center of the roof, which also served as a smokehole. A vertical shaft brought air for the ceremonial fire on the floor. The sipapu, or small opening into the ground, a symbolic entrance to the underworld or Mother Earth, indicates religious purposes for the kiva, although it probably was used for recreation as well. The resemblance between these kivas and the modern Pueblo ceremonial chambers affords an important clue to possible relationships between the prehistoric mesa dwellers and modern Pueblo tribes.

Thus the Developmental Pueblo society moved in architecture from the pithouse to the pueblo; from relatively crude to quite advanced construction. And there were other changes. The dull, natural hues of the pottery were abandoned for clear white, which showed designs more advantageously. Flat metates, as contrasted with the earlier trough-shaped stones, provided improvement in grinding corn.

The most novel change was the introduction of the wooden cradle board replacing the Basketmakers’ pliable, pillowed reed-and-grass cradle. When archaeologists unearth Pueblo skeletons they find the skulls deformed, with an exaggerated flattening of the back. For a time scholars believed that the Basketmakers and the Pueblos were two distinct, unrelated groups because of this radical difference in head shapes. More recently, with added study of physical characteristics, many authorities have come to believe that the skull differences resulted largely from the type of cradle board. The hard wooden board of the Pueblos was probably borrowed from some other group and became a popular fad.

The last two centuries of life on the mesa saw the climax of the long advance from simple agriculture to a complex culture: the Great, or Classic, Pueblo Period of ad 1100 to 1300. During these two hundred years the Pueblos achieved their finest architecture. They carefully cut and laid up masonry walls; they plastered and decorated some of those walls with designs. Their villages became larger, containing many rooms; some rose to heights of three and four floors. The ruins of Far View House provide an interesting example. Here the people built an integrated complex of living and storage rooms, kivas, a walled court, and a tower.

Farming also reached new heights. Most crops were cultivated on the mesa top, but some small, terrace-like patches at the heads of the canyons were also used. In the floors of the canyons, the Pueblo people constructed dams for water storage—the earliest irrigation works in Colorado. Corn, beans, squash, and gourds were the main crops. For some items the people probably were dependent on trading expeditions outside the region, perhaps to the south. Cotton probably was not grown in any quantity on Mesa Verde, so the presence of woven cotton cloth among the ruins suggests trade with others. Salt, sea-shells, and turquoise also were acquired through trade.

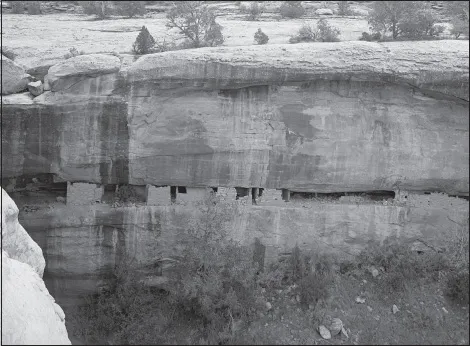

Little Long House, Mesa Verde National Park, as seen by photographer George Beam.

This commerce with other people is one of the fascinating imponderables of these mysterious people. Just one old bill-of-lading would tell us much about them. But the Pueblo people never developed a system of writing. And that was only one of their limitations. They had no horses or livestock. They never developed the wheel. They used no metals.

Despite these limitations, the Classic Pueblo Period was a time of greatness. Some archaeologists also believe it was a period of regimentation, with previously developed patterns used over and over again. The kivas became highly standardized, suggesting more rigid ceremonial practices. There also appears to have been a drawing together of the population and possibly a decline in total numbers. The pueblo dwellings became much larger, and tall round towers were built. Since the towers were usually connected by an underground tunnel with the kivas, they may have been used in ceremonies. But their strategic location, and possible use as watchtowers, also suggests the need for vigilant defense.

And then the most startling innovation occurred. The people deserted the mesa top and built their pueblos in the caves in the walls of the canyons. Many families were involved in this descent to the caves; estimates of 600 to 800 separate cliff dwellings demonstrate the magnitude of the migration. Paradoxically, it was here, within the confined caves, that the pueblo builders produced their architectural masterpieces: Spruce Tree House, Square Tower House, and, most marvelous of all, Cliff Palace.

Cliff Palace contained more than 200 rooms, forming a city in itself. It was built in terraces, rising three and four stories in places, with twenty-three kivas and housing adequate for more than 200 people. The quality of the masonry construction and the interior plastering and painting of the walls in red and white represent refinements beyond anything known before.

Again the suggestion seems obvious: Defensible sites for homes had become a necessity. Certainly the cliff dwellings in the almost inaccessible canyon walls provided an uncommon measure of security. Apparently some great danger, not present earlier, had come to threaten the mesa dwellers. But who or what that danger might have been can only be guessed at. Raids by nomadic tribes might have provided the impetus to drive the people from the mesa into the caves of the canyons. Or they may have fled a civil war. Most of the Anasazi, as they became known, continued to live in valleys and mesas throughout the region. Only a small minority lived at Mesa Verde.

Whatever caused the concentration, it marked the beginning of the end of the Pueblo people in the Mesa Verde area. For a few more generations the cliff dwellers lived in their apartment houses in the caves. Then, at the end of the thirteenth century, they withdrew. They probably drifted southward; at least, tribal traditions of the Tewa, Flopi, and Zuni Indians tell of earlier migrations from the north.

The fact that the last quarter of the century—the years from 1272 to 1299—were years of extended drought may partly explain the withdrawal. They may have thought their gods had abandoned them and they may have decided to seek other lands with better, more reliable water supplies. But they had survived earlier long droughts, so there had to be another reason for their departure.

Perhaps it was a combination of overpopulation and environmental changes. They had farmed the same land for centuries, decreasing its fertility, and they had hunted and cut timber in the same region, reducing these resources. At the same time greater numbers of Anasazi lived in the area; population pressures, decreasing natural resources, and a changing environment may have been too much to overcome. For the first, but not the last time in Colorado, humans and the environment had clashed.

B...