eBook - ePub

Travels in the Air by James Glaisher, Camille Flammarion, W. de Fonvielle, and Gaston Tissander

- 466 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Travels in the Air by James Glaisher, Camille Flammarion, W. de Fonvielle, and Gaston Tissander

About this book

In the 21st century - the age of the budget airline - where quick and reliable air travel is available to a large segment of society, it seems hard to comprehend that it is less than 250 years since the first human took to the skies.

Although the wing of the bird seemed like the most obvious natural mechanism to attempt replicate, it was actually contained hot air, as demonstrated by the Montgolfiers and their balloon, that gave birth to the era human aviation. Since the first manned balloon flight in 1783, developments have come thick and fast, the airship, the aeroplane, and finally the space shuttle.

This reprint of a classic publication written by some of the pioneering aeronauts, details the interesting history and major events of the lighter-than-air period of aviation. Complete with illustrations and a brand new introduction, it gives a fascinating insight into aviation before the aeroplane.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Travels in the Air by James Glaisher, Camille Flammarion, W. de Fonvielle, and Gaston Tissander by Various in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Aviation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I.

AËRIAL TRAVELS OF MR. GLAISHER.

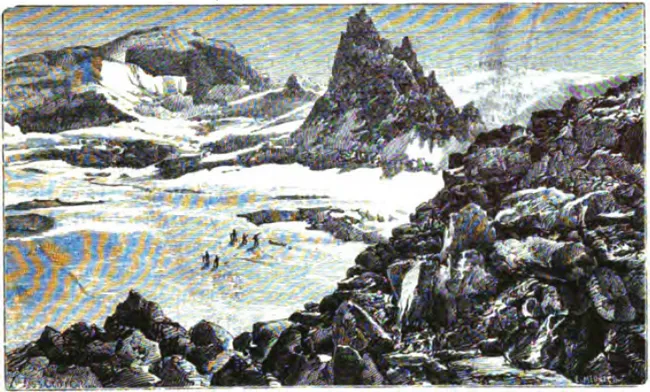

ASCENT OF MONT BLANC.

TRAVELS IN THE AIR.

INTRODUCTION.

I HAVE elsewhere expressed my opinion that the Balloon should be received only as the first principle of some aërial instrument which remains to be suggested. In its present form it is useless for commercial enterprise, and so little adapts itself to our necessities that it might drop into oblivion to-morrow, and we should miss nothing from the conveniences of life. But we can afford to wait, for already it has done for us that which no other power ever accomplished; it has gratified the desire natural to us all to view the earth in a new aspect, and to sustain ourselves in an element hitherto the exclusive domain of birds and insects. We have been enabled to ascend among the phenomena of the heavens, and to exchange conjecture for instrumental facts, recorded at elevations exceeding the highest mountains of the earth.

Doubtless among the earliest aëronauts a disposition arose to estimate unduly the departure gained from our natural endowments, and to forget that the new faculty we had assumed, while opening the boundless regions of the atmosphere as fresh territory to explore, was subject to limitations a century of progress might do little to extend. In the time of Lunardi, a lady writing to a friend about a balloon voyage she had recently made, expresses the common feeling of that day when she says that “the idea that I was daring enough to push myself, as I may say, before my time, into the presence of the Deity, inclines me to a species of terror”—an exaggerated sentiment, prompted by the admitted hazard of the enterprise (for Pilâtre de Rozier had lately perished in France, precipitated to the earth by the bursting of his balloon), or dictated by an exultant and almost presumptuous sense of exaltation: for the first voyagers in the air, reminded by no visible boundary that for a few miles only above the earth can we respire, appear to have forgotten that the height to which we can ascend and live has so definite a limitation.

But no method more simple could have been imagined than that by which the aëronaut ascends, and which leaves the observer entire freedom to note the phenomena by which he is surrounded. With the ease of an ascending vapour he rises into the atmosphere, carried by the imprisoned gas, which responds with the alacrity of a sentient being to every external circumstance, and lends obedience to the slightest variation of pressure, temperature, or humidity. The balloon when full and on the earth, with a strong wind, is vehemently agitated, and if a stiff breeze prevail during the progress of inflation, it is for the time almost ungovernable. When prepared for flight it offers the greatest powers of resistance to mechanical control, and, bent on soaring upwards, struggles impatiently to be free.

In a line of perpendicular ascent the balloon has a motion of its own. It therefore rises or falls according to the action of the atmosphere upon the imprisoned gas. The second motion, which, united to the first, carries the balloon out of the perpendicular line on rising, and directs its onward motion in a plane, is not inherent in the balloon, but is due to the external force of horizontal currents which sweep it in the direction of their course, and communicate a compound motion we can neither direct nor calculate. The simple inherent motion we can repeat at will.

I believe the most timorous lose their sense of fear as the balloon ascends and the receding earth is replaced by the vapours of the air; and I refer this confidence chiefly, as has been suggested, to the consciousness of isolation by which the balloon traveller feels more like a part of the machine above than of the world below. Thus situated, he is induced to forget the imperfections of the machine in witnessing the close accordance of its movements with those of the surrounding clouds. The balloon strives to attain a height where it may rest in equilibrium with the air in which it floats; its ascent is checked by allowing gas to escape by the valve, and by the weight of ballast, but facilitated by keeping the gas in and discharging the ballast. These are the methods by which it is made to rise or fall at the will of the aëronaut, and the only objection to the frequent employment of the valve and the use of ballast is to be found in the greatly abbreviated life of the balloon and too rapid diminution of its powers which follow.

Up to the time of the Balloon we had no means of ascending by which we could test the conditions of the atmosphere for even a mile above the surface of the earth, apart from the terrestrial influences and the inevitable labour of ascending the mountain side. When, therefore, Messrs. Charles and Robert made their first ascent, and recorded the history of their sensations and the conditions of the atmosphere at various elevations, as the natural incidents and circumstances of their voyage, a practical application of the Balloon was thus spontaneously suggested.

Before Gay-Lussac solicited the French Government for the use of the balloon in which he ascended to the height of 23,000 feet, M. de Saussure, of Geneva, had alone made observations at a height of 15,000 feet and upwards; a distinction he had won by accomplishing the desire of his life, and ascending to the summit of Mont Blanc.

This memorable journey De Saussure performed in the summer of 1787, four years after the first balloon ascent of Messrs. Robert and Charles in a hydrogen balloon from Paris, and seventeen years before Gay-Lussac made his ascent for the advancement of science. The weather was favourable, and the snow compact and hard. Accompanied by his servant and eighteen guides, De Saussure began his journey. There was no difficulty or danger in the early part of the ascent, their footsteps being either on the grass or the rock itself. After six hours’ incessant climbing, they found themselves 6,000 feet above the village of Chamouni, from which they started, and 9,500 feet above the level of the sea At this height, the same to which M. Robert had attained in his balloon, De Saussure and his party prepared to encamp, and slept under a tent on the edge of the glacier of the Montagne de la Côte. By noon the next day they were 2,000 feet above the level of perpetual frost In the afternoon, after eight hours of climbing, they had arrived at an elevation of 13,300 feet above the level of the sea. They were now on the second of the three tremendous steppes which extend from 800 to 1,300 feet each between Les Grands Mulets and the summit of Mont Blanc. On the second of Les Mulets, De Saussure intended to pass the night. The guides dug out the snow for their lodging, and threw some straw into the bottom of the pit, across which they stretched a tent. Their water was frozen, and they had but a small charcoal brazier, which proved quite insufficient to melt snow for twenty persons. When morning came, they prepared again for departure. The cold was excessive, but before breakfast could be obtained it was necessary to melt the snow which also served for the water in their journey to come. They crossed the great ice plain, or Grand Plateau, without difficulty; but the rarefaction of the air began to affect their lungs, and this inconvenience continued to increase at every step. A prolonged rest was made in hopes of recruiting their forces, but with little advantage. They had not gone a dozen steps before they were compelled to halt to recover breath, and in this manner, slowly and with great toil and discomfort, the summit was reached.

“At last,” writes De Saussure, “I had arrived at the long-wished-for end of my desires. As the principal points in the view had been before my eyes for the last two hours of this distressing climb, almost as they would appear from the summit, my arrival was by no means a coup de theâtre; it did not even give me the pleasure that one might imagine. My keenest impression was one of joy at the cessation of all my troubles and anxieties: for the prolonged struggle and the recollection of the sufferings this victory had cost me produced rather a feeling of irritation. At the very instant that I stood upon the most elevated point of the summit, I stamped my foot on it more with a sensation of anger than pleasure. Besides, my object was not only to reach the crown of the mountain: I had to make such observations and experiments as alone would give any value to the enterprise, and I was afraid I should only be able to accomplish a portion of my intentions. I had already found out, even on the. plateau where we slept, that every careful observation in such a rarefied atmosphere is fatiguing, because the breath is held unconsciously; and as the tenuity of the air is obliged to be compensated for by the frequency of respiration, this suspended breathing causes a sensible feeling of uneasiness. I was compelled to rest and pant as much, after regarding one of my instruments attentively, as after having mounted one of the steepest slopes.”

De Saussure spent three hours and a half in observations, and after four hours passed on the summit, began with his party to descend. They passed the night on Les Mulets, the third since they left Chamouni, and De Saussure writes: “We supped merrily together and with famous appetites. It was not until then that I really felt pleased at having accomplished the wish of twenty-seven years. At the moment of my reaching the summit I did not feel really satisfied. I was less so when I left it: I only reflected then upon what I had not done. But in the stillness of the night, after having recovered from my fatigue, when I went over the observations I had made; when especially I retraced the magnificent expanse of the mountain peaks, which I had carried away engraven in my mind; and when I thought I might accomplish on the Col de Géant what most assuredly I should never do on Mont Blanc, I enjoyed a true and unalloyed satisfaction.” The simple narrative of this eminent man is throughout a commentary upon the use of the Balloon for the purpose of vertical ascent. To be carried up with speed and certainty at any number of feet per minute, with instruments complete and carefully prepared for observation, the observer seated as calmly as in his observing room at home, are advantages which speak for themselves. The observations of to-day can be repeated to-morrow, and successively throughout the seasons of the year, and at different hours of the day; and the importance of this repetition is rendered clear by considering of what slight value is a single set of observations, whether in meteorology or any other branch of inquiry, except to appease curiosity, and how little gain to science is one isolated day’s experience; and yet to ascend Mont Blanc was the one great fact of De Saussure’s life.

The view which offers itself to an aëronaut seated conveniently in the car of a balloon is far more extended than any the eye can embrace within its scope from the summit of a lofty mountain. It is gained without fatigue, but then there is no succession of magnificent scenery which compensates for the toil of the Alpine traveller, and suggests a variety of observations unknown to the voyager of the atmosphere. To the latter, situated at a height above the earth, separated from all communication with it, the scenery on its surface is dwarfed to a level plane, and the whole country appears like a prodigious map spread out beneath his feet. Better than the Alpine traveller he can trace the history of physiological sensations, and pursue the observations of meteorology. In the one case he travels free from the effects of muscular exertion, which makes fatigue so formidable in the higher regions of the earth’s scenery, and, apart from all terrestrial influences of soil and temperature, scans the true conditions of the atmosphere.

On looking into the annals of aërostation, I do not find that balloon travellers in general have cared to ascend beyond the height to which De Saussure attained on the summit of Mont Blanc, and the greater number of ascents are within this limit. Most aëronauts have taken care to keep well within recognition of the visible scenery of the earth, and would seem to have been too eager to enjoy the privilege of movement, and the varied prospect in any direction they could travel, to wish to prove their capacity for vertical ascents. We have few reliable observations to a great height. High ascents have now and then been attempted by professional aëronauts eager to gain the attention of the public and enlist its sympathy in their results. Voyages in illuminated balloons by night, in weather not always suitable, were performed successively by M. Blanchard, and after him by M. Garnerin, who preceded the late Mr. Green. Beyond the passing sensation of the moment, recorded in the public prints of the day, their ascents have left no permanent trace in the history of the Balloon. The ascent made by M. Charles, after a joint expedition of Messrs. Charles and Robert, is the first experience of value we have to compare with others. It was, we may suppose, the first occasion on which sunset was witnessed a second time in the same day by any living mortal.

On December 1, 1783, having descended and landed his companion, M. Charles determined to ascend alone. It was towards sunset, and ballast could not be readily procured. Without waiting, therefore, M. Charles gave the signal to the peasants, who were holding his machine, to let go; “and I sprang,” says M. Charles, “like a bird into the air. In twenty minutes I was 1,500 toises high, out of sight of terrestrial objects. The globe, which had been flaccid, swelled insensibly; I drew the valve from time to time, but still continued to ascend. For myself, though exposed to the open air, I passed in ten minutes from the warmth of spring to the cold of winter: a sharp, dry cold, but not too much to be borne. In the first moment I felt nothing disagreeable in the change. In a few minutes my fingers were benumbed by the cold, so that I could not hold my pen. I was now stationary as to rising and falling, and moved only in a horizontal direction. I rose up in the middle of the car to contemplate the scenery around me. When I left the earth, the sun had set on the valleys; he now rose for me alone; he presently disappeared, and I had the pleasure of seeing him set twice on the same day. I beheld for a few seconds the circumambient air, and the vapours rising from the valleys and rivers. The clouds seemed to rise from the earth, and collect one upon the other, still preserving their usual form, only their colour was grey and monotonous from the want of light in the atmosphere. The moon alone enlightened them, and showed me that I had changed my direction twice. Presently I conceived, perhaps a little hastily, the idea of being able to steer my course. In the midst of my delight I felt a violent pain in my right ear and jaw, which I ascribed to the dilatation of the air in the cellular construction of those organs as much as to the cold of the external air. I was in a waistcoat and bare-headed; I immediately put on a woollen cup, yet the pain did not go off till I gradually descended.”

M. de Meusnier made various calculations as to the height attained by M. Charles, and calculated it to have been at least 9,000 feet. The temperature at the time of starting was 47° on the earth, but in ten minutes had descended to 21°. When M. Charles came down and landed his companion, they were met by the Duc de Chartres and some French noblemen, who had followed on horseback for twenty miles the course of the balloon. A contemporary pamphlet records the particulars of the ascents, and has a postscript to the e...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- The Early History of Flight

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Contents

- List of Chromo-Lithographs

- List of Lithographs

- List of Woodcuts

- Part I. Aërial Travels of Mr. Glaisher.

- Part II. Travels of M. C. Flammarion.

- Part III. Travels of MM. Fonvielle and Tissandier.

- Conclusion