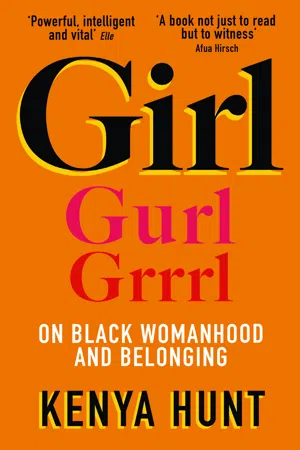

1 Girl

Girl! GWORL. Gorl. Guhl. Gurl. Grrrrrlll.

‘Mommy, why is it that every time you’re on the phone or with your friends it’s always girl, girl, girl, girl?’ my son asked me two years ago, as I was tucking him into bed for the night. I was amused. Mostly at the sight and sound of myself through my five-year-old’s eyes and ears — he had gotten my animated pacing and high-pitched intonation just right — but also at the idea that I used the word enough for him to pick up on it.

‘I hadn’t realised, sweets. Do I really say it that much?’

‘Girl! You do,’ he said with a childish smirk, before turning over and closing his eyes. I tried to swallow my laughter as I turned off the light and tiptoed out of the room.

In my life I’ve used many pet names for the people I know and love: sis, luv, beauty, lovebug, babes, hon, pumpkin, doodlebug, sweets, bae, dumpling and peanut among others. But throughout my evolving networks of friends — and especially so among my Black chosen sisters — one term of endearment remains: girl. Equal parts greeting, exclamation and rallying call all at once.

As long as I can remember, girl was the root word in the unique love language between Black women, regardless of age. ‘Girl, you got it. Just go out there and do your best,’ my mom, Precious, would say while giving me a pre-dance recital peptalk during my childhood in Virginia. ‘Babygirl, you crazy,’ my aunt, Gloria, all gregarious joy, would tell my little sister, April, scooping her up in a hug, upon discovering that the child had piled on her hair pieces, blouses and bangles in a game of dress-up.

‘Hey, girl, hey,’ my dorm-mate at university would say in a conspiratorial, hushed voice, unveiling a box of caffeinated soft drinks and Krispy Kreme donuts as we prepared to pull an all-nighter for one upcoming exam or another. ‘Guuurl,’ my friends and I would sing along to Destiny’s Child’s ‘Girl’ as we got dressed for a night out, placing extra emphasis on the vocal runs every time Beyoncé, Michelle and Kelly would hit the title word. ‘Guuuuurl,’ we would sing along, imploring our imaginary friend to let a philandering man go, adding a vocal run or two and a fluttering hand for extra dramatic effect. Girl was a one-word lingua franca that transcended class, generations and geography. A word we used with each other to show affection and acknowledge shared history, experiences and aspirations.

When I entered the working world as a graduate, I became conflicted about the colloquialism. On the one hand, I was steeped in feminist culture as an assistant editor at Jane magazine, an iconic title in the feminist publishing community. Girl was a polarising word. Some viewed it as an infantilising condescension (that’s ‘womyn’, please and thank you), others as an empowering subversion (hey riot grrrls).

And then there was the hipster racism I’d inevitably encounter at dive bars after work. Bearded white boys in flannel shirts telling me, ‘You go girl’, in an annoying mimicry of an equally annoying, old imitation of Black women that comedian Martin Lawrence popularised in his eponymous sitcom years before. Or young white gay men on the fashion party circuit who mistakenly thought their queerness excluded them from buying into cultural stereotypes, and who caused me to stiffen with their awkward greeting: ‘Hey girl, I like your hair. Is it yours?’

I didn’t recognise myself in any of the pantomimes, though this was clearly how many envisioned Black women — one neck-rolling monolith. I refused to play to type and fit in with a narrow idea of what Black women were supposed to be.

I felt more kinship with the plethora of girls in the Black and brown ballroom scene. Yes, the icons in Paris Is Burning popularised the now commonplace social media age lexicon that includes ‘yassss’, ‘girl’, ‘read’, and ‘honey’ to the mainstream. These expressions — essentially innocuous, everyday words given entirely new meanings — originated with us, Black women (cis and trans), and can be traced back through generations to our hair salons, kitchens and churches. So, I’d code switch, limiting the love language to conversations with my closest Black women friends and family members back home.

I hadn’t quite realised the Americanness of this, though, until I moved to London from New York in late 2008 and felt the need to build up my own network of Black women friends after tiring of always being The Only in my work and social life. I befriended Ghanaian, Nigerian, Jamaican and Black British women with sharp opinions, bold voices and thriving careers. Women who didn’t dot their anecdotes with a loud ‘girl’ for emphasis, or use it as an affectionate preface to a warm hug or effusive compliment. ‘Girl, you did that.’ So it dropped out of my daily lexicon, only coming out for marathon phone catch-ups with Stateside girlfriends.

But as a new wave of racial discourse and Black consciousness rolled in with the Obama administration in the late aughts, ‘girl’ took on a new life of its own, crossed the pond and worked its way through the entire diaspora. We became, in a word, magic.

Like most cultural touchpoints in the 2010s, it began with a Tweet. #BlackGirlsAreMagic was created by one CaShawn Thompson to counteract a wave of bad PR in the form of tired stereotypes and lies. No, of course we’re not shrill, unmarriageable, ugly and uneducated. We are strong, beautiful, originators of movements and culture the world over. As I write this, I’m listening to the official #BlackGirlMagic playlist on Spotify, filled with music by women of colour from across the world: London, Los Angeles, Lagos, New York, Ekiti, Chicago and Atlanta, among others. There are Black Girl Magic T-shirts, books, book clubs and websites. Not that we needed the hashtag to tell us who we are — we don’t need a hashtag as validation. But the shortened #Blackgirlmagic and the like, including #Blackgirljoy and #carefreeBlackgirl, took off, broadcasting to the world what we already knew: when it comes to excellence, we’re not new to this (to quote Drake, vocal appreciator of Black women), we’re true to this.

Some people are validation junkies, addicted to the likes and shares, the digital pats on the back. But I get my highs from the hit of underestimation. Give me a ‘meh’ and I’ll make you eat it. Disregard me and I’ll show you. I get a rise out of proving people wrong. During the many interviews I’ve given as a fashion editor about the lack of diversity in the business, people sometimes ask me, ‘What does it feel like to make it in an industry filled with people who don’t look like you?’

It’s being 19 years old and told by a university professor in Charlottesville, Virginia to manage my expectations and try a career in teaching high school when I expressed a desire to move to New York and work in magazine publishing. It’s being told to go back to the drawing board during a staff meeting at my second magazine publishing job in New York, when the editor dismissed my pitch about a story on teenage moms with the nonchalant and wholly inaccurate logic that it ‘was no good because the story would just be about Black girls, and no one wants to read that.’ It’s an editor sitting next to you in the front row during New York Fashion Week and showing you a photo of the African tribeswoman who will be her toddler’s nanny during an extended winter stay at a national reserve in South Africa. It’s to be repeatedly asked to go on television to comment about why there are so few of you in media, television and fashion, as if it’s the only subject you’re qualified to speak about.

It’s to be seated next to a model agency owner at a work dinner, who tells you you’re pronouncing your name wrong. ‘I know the most luxurious lodge in Keenya. Where do you like to stay when you’re there? Surely you’ve been to the country before, no? Not even Nairobi? Then why did your parents name you Keenya? You pronounce it “Kehn-ya” you say? Not “Keenya”? Hmmmm, are you sure?’ It’s to restrain yourself from using the other kind of ‘girl’—’Girl!’ — as admonishment and verbal eye roll. The kind of ‘girl’ I use for women who test my patience, no matter what their race. As in, ‘Girl, stop! Old white colonialists pronounce it this way.’ It’s to sit in a staff meeting and suggest a Black pop star for the cover only to be told, ‘But we just had a Black woman on the cover last month. And it would be too weird to have two in a row.’

But that was then. And this is now, the age of Black Girl Magic in which we’re owning the expansiveness of Blackness at its cross-section with womanhood, tracing its myriad shapes and textures, during a time when what it means to be a Black woman has permeated every level of public discourse from the unbelievably tragic (Sandra Bland, Breonna Taylor, Atatiana Jefferson, and a tragically long list of others) to the tragi-comical (Rachel Dolezal).

What and who is Black Girl Magic? She’s Solange Knowles dressed in white, dancing on the streets of New Orleans. It’s my favourite photo of Malia and Sasha Obama, with girlfriends, trailing behind their dad, as they deplane Air Force One. It’s Black Lives Matter founders Patrisse Khan-Cullors, Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi galvanising a global movement against the brutalisation of Black bodies. And Bernardine Evaristo winning the Booker Prize, the first Black British author to do so. It’s Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie interviewing Michelle Obama about her record-breaking book in front of a sold-out theatre in London. And a video clip of Michelle Obama congratulating Beyoncé on her record-breaking Netflix special, Homecoming — a rich, rousing, and very Black, tribute to historically Black universities. It’s nineteen Black women being elected to judgeships in Texas, a longstanding conservative state, during the American midterm elections. And five Black women, their backgrounds spanning South Africa, Jamaica and America, winning the world’s five most iconic beauty pageants, Miss America, Miss USA, Miss Teen USA, Miss World and Miss Universe. It’s Black actresses, singers and models dominating UK and US women’s magazines for the first time in history, in September 2018. And South African two-time Olympic 800m champion Caster Semenya declaring herself ‘supernatural’ as she sought to qualify for the Tokyo Olympics. It’s Kamala Harris running for President. And all of us avowing our solidarity in the face of global pandemics and tragedy. Women, girls, daring to be true to the gradations of ourselves in a world where anyone not named Beyoncé, Rihanna or Lupita tends to get depicted as chronically angry, perennially overlooked, forever victimised, unfailingly ratchet, and more. That’s not how I view myself. That’s not how anyone I know views themselves.

The world expects the more familiar, stereotypical image of us as the server of side eyes and roller of necks. But Black Girl Magic is a celebration that frees us from the confines of narrow expectation or subtext.

Girl!

I began hearing the call-out beyond my network of Black girlfriends. ‘Girl,’ Kim Tatum said, greeting fellow trans activist Rhyannon Styles during a podcast episode I hosted during my time as an editor at British ELLE. We were discussing what it meant to be trans, an idea that had entered the mainstream for the first time through global headline makers such as Orange Is the New Black star Laverne Cox and writer Janet Mock.

‘Damn, girl, you look fabulous,’ an Instagram post by the body positivity activist BodyPosiPanda read, inviting women to embrace their most authentic, unfiltered selves and learn to love the back fat, stretch marks and acne scars.

‘I’ve got your back, girl,’ I overheard a middle aged white saleswoman say to her co-worker, hair streaked with grey, as she fixed a frozen cash register during a shopping trip.

In a way, the word had become a positive affirmation and a vocal show of unity in our age of outrage. Yet there is little written about its use in this way.

I’ve watched ‘girl’ come full circle, just as my relationship with it has. I now openly use it to show sisterly affection, shared cultural experiences or not — as do many Londoners I know. When I checked in on a pregnant friend in south London who had birthed a baby boy after three days of labour, her reply, a single word sent via text, spoke volumes about joy, exhaustion, relief and perseverance: ‘Girl…’

She didn’t need to say anything more.

At a women’s festival at the Saatchi Gallery where I appeared as a speaker, the green room was a joyous din of loud laughter, chatty group hugs and enthusiastic ‘hey girls’ between authors, journalists, models, activists and athletes. On stage, I asked Halima Aden, the Kenyan-born woman who made history as the world’s first hijabi supermodel, if she ever felt a weight of responsibility as A First. ‘Well, girl, when you put it that way,’ she laughed before admitting she does.

Here, ‘girl’ wasn’t tied to any specific country of origin. Just as it wasn’t during the London Women’s March months later where protestors of all ethnicities and ages walked with placards featuring such ballsy messages as ‘Girls just want to have fun-damental human rights’ and ‘Girls doing whatever the fuck they want.’

Girls! Girl. Gurl. Girl, hey. Girl, bye. Girl, stop. Girl, go. Girl, we see you, and feel seen.