![]()

1

History of the Therapeutic Uses of Cannabis

Cannabis is a genus of herbaceous flowering plants in the family Cannabinaceae. There is some dispute whether the three main types of Cannabis—C. sativa, C. indica, and C. ruderalis—are three separate species or different strains or varieties of the same species. In the United States today, the term hemp is used to refer to varieties of cannabis*1 that contain 0.3 percent or less of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the plant’s main psychoactive constitutent, whereas the common term marijuana refers to cannabis that has more than 0.3 percent of THC and can induce euphoric effects in users. In most European countries, the threshold is 0.2 percent, and in Switzerland it is 0.1 percent. However, both plants are classified as Cannabis sativa L.

The dried leaves and flowering tips of the plant, high in THC, and the resin extracted from the plant have gone by many names over the millennia. In Spanish, cannabis is commonly called hierba or María; names coming from various other cultures for cannabis preparations are bhang, charas, dagga, khif, ganja, diamba, maconha, canapa, and chamvre. In English, common slang terms are grass, weed, shit, and pot.

Today, we believe that the cultivation of cannabis in Asia goes back many thousands of years. Before the common era, Western Asia was the departure point for the diffusion of cannabis to Europe and the African continent and then, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, to North, Central, and South America.

For a very long time, people have been using both the nonpsycho-active and psychoactive varieties of cannabis. Hemp has been used for its fibers and for its seeds. Hempseeds, which have great nutritional value, are used in the preparation of many dishes. Since long ago, hemp fiber, well known for its great versatility, has been used to make paper, fabric, and rope. The Phoenicians who traversed the Mediterranean three thousand years ago, as well as the Egyptians in the time of the pharaohs, used this very tough material to construct their sails and fishing nets. In China, the first paper products (an invention that was kept secret for a long time) were made with hemp several centuries before the beginning of the common era. But it was only in the ninth century that the Arabs introduced it to the West, where it replaced papyrus and clay tablets. Gutenberg’s first Bible, like all the other books of that time, was printed on paper made from a mixture of hemp and flax.

The psychoactive components of the plant were also known before the common era and were already used in healing rites and ceremonies in numerous cultures. Cannabis was identifed as a sacred plant in the Vedas, religious Hindu texts that date back to about 1500 to 1300 BCE. The earliest written reference to the healing properties of cannabis is found in the Rh-Ya, a Chinese pharmacopiea of about 1500 BCE. As for its numerous therapeutic properties, now rediscovered today, such properties were certainly known in the Middle East, from whence the traditional applications used in treating certain neurological disorders were transmitted to us. Today, we can still profit from this experience that is hundreds if not thousands of years old.

In the eighteenth century, Europeans traveling in Arab countries and in Asia discovered cannabis containing high levels of THC. The term Indian hemp was introduced for the first time by the German naturalist Georg Eberhard Rumpf (1627–1702). However, before the nineteenth century, Indian hemp was not much used in medicine in either Europe or America, and most often, it was met with a certain skepticism.

In 1823, an article on the successful use of Indian hemp in the treatment of whooping cough appeared in the Hufeland Journal: “The extract of cannabis was used at the Polyclinic in Berlin in the emergency treatment of a patient suffering from a convulsive cough. The same extract in powder form, mixed with sugar, in a dose of 4 grams was prescribed daily” (Dierbach 1828, 420). In 1830, the therapeutic application of Indian hemp was described in detail, for the first time in Europe, by Theodor Friedrich Ludwig Nees von Esenbeck (1787–1837), professor of pharmacology and botany at the University of Bonn, Germany. Certain doctors, notably Samuel Hahnemann (1755–1843), prescribed cannabis extract for treating numerous cases of nervous disorders where medical practitioners would more usually have used opium or Hyoscyamus niger (henbane). He found that cannabis had fewer side effects than the two alternatives.

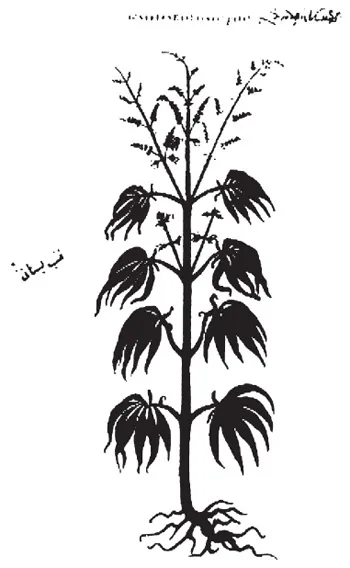

Figure 1.1. The oldest image representing cannabis, found in the Manuscriptum Dioscorides Constantinopolitanus held at the British Museum in London and dating from the first or second century after Christ, later annotated in the Arabic language

Figure 1.2. Woodcut found in the Contrafayt Kreüterbuch of Otto Brunfels (1532)

GREAT BRITAIN

The Scotsman Sir William Brooke O’Shaughnessy, doctor, scientist, and engineer, was a veritable pioneer in the therapeutic use of cannabis in Western Europe—and specifically in the use of its psychotropic properties. In 1833, as an employee of the British East India Company, he traveled for the first time to India. He was thirty-three years old. Very quickly he became interested in the therapeutic potential of cannabis, and in 1839 he published a synthesis of his experiments, which aroused considerable interest in Great Britain. First of all, he became aware of the various traditional therapeutic uses of the plant in India, and he then conducted studies on animals and humans to fully understand its action and to better evaluate its side effects.

Following his initial investigations, he came to the conclusion that, because of the “completely harmless nature of cannabis resin,” a complete study ought to be conducted of clinical cases in which “its obvious qualities indicated greater therapeutic benefit” (O’Shaugnessy 1973). Consequently, tinctures of cannabis (extracts of cannabis resin dissolved in ethyl alcohol), in doses of between 65 and 130 mg, were prescribed for patients suffering from rheumatism, tetanus, rabies, epileptic spasms, cholera, and delirium tremens. Of three cases treated for rheumatism, two were “almost healed in three days,” although the administration of these high doses induced considerable side effects, such as total paralysis and uncontrollable behavior. In the third case, no reaction to the treatment was observed; it was only later that the patient confessed that he regularly took cannabis. This led to the first indications of the development of a tolerance.

Other studies conducted with weaker doses led to similar conclusions: “Reduction of pain levels in most patients, notable appetite stimulation with all patients, undeniable aphrodisiac effects and feelings of great spiritual happiness. Everyone followed the same progressive development and none of the cases presented headaches or nausea as a response” (O’Shaugnessy 1973).

Convulsions and spasms induced by rabies or tetanus were controlled with the administration of high dosages of cannabis. In the case of tetanus, the cannabis acted positively on the progress of the disease and was administered in doses in the range of 650 mg for cases judged to be “hopeless.” O’Shaughnessy observed muscle relaxation as well as a cessation of “convulsive tendencies.” Similarly, the observations conducted on epileptic spasms were encouraging. As for the treatment of cholera, excellent results were obtained, although more often with Europeans than with Indians, who were regular consumers of bhang, an edible paste made from the leaves and flowering tops of cannabis. O’Shaughnessy also identified the antiemetic effects of cannabis.

As a result of reports published by this illustrious pioneer, the use of cannabis expanded in Europe and in America, where it quickly turned into a widely accepted medication. Numerous new doctors then spread the news of their experiments.

In 1845, Michael Donavan (1790–1876), an Irish apothecarist and chemist, described the effectiveness of cannabis in the treatment of intense neuralgic pain in the arms and fingers, inflammation of the knee joint, facial neuralgia, and sciatic nerve pain in the pelvis, the knees, and down to the feet. In addition, he observed cannabis’s stimulating effects on appetite. The same year, Dominic Corrigan, an Irish physician, described several cases of Huntington’s chorea (Sydenham’s chorea) and of neuralgia that could be treated successfully with a cannabis tincture. As found by other doctors, he took note of the substantial variability in the effectiveness of the active element, which today can be attributed to the varying concentrations of THC in the plants. In one single case, the administration of twenty drops of this tincture led to a “transitory loss of almost all muscle tone followed by sleep whereas in another case a patient received three times a day for a week a similar dosage without any significant problem and with successful results.”

The British doctor John Clendinning reported in 1843 on trials conducted on several clinical cases: “I have no hesitation in confirming that prescribing cannabis, with the exception of notably rare cases, has been shown to have very precise effects as a somniferous or hypnotic agent producing sleep; as an analgesic . . . ; as an antispasmodic for the relief of cough and cramps; as a central nervous system stimulant to relieve sluggishness and anxiety; as a cardio tonic; and as a stimulant of good humor. All these effects were observed in both acute and chronic disorders, in both young and old and in both men and women.”

Other British doctors, such as Fleetwood Churchill (1849), Alexander Christison (1851), John Grigor (1852), Horace Dobell (1863), A. Silver (1870), John Brown (1883), Robert Batho (1883), and R. H. Fox (1897), also reported on the analgesic properties of cannabis in the treatment of rheumatism, sciatica, migraines, pain of various origins, muscular cramps, asthma attacks, insomnia, uterine contractions in childbirth, heavy menstrual bleeding (menorrhagia) as well as treating dependency on opiates or chloral hydrate.*2 According to Dr. Edward A. Birch, in a seminal article published in The Lancet in 1889, Indian hemp immediately reduces “the desire for chloral or opium” and stimulates the appetite.

In his time, Sir John Russell Reynolds (1828–1896), a well-known professor of medicine in London and personal physician of Queen Victoria, for whom he prescribed cannabis every month to treat menstrual disorders, summarized his experiments in 1890, collected over a period of thirty years, relating to medicinal compounds based on cannabis: “Indian hemp, as long as it is administered with caution, is one of the most precious medicines that we have available” (Reynolds 1890). He specified that cannabis could be used successfully to treat the insomnia of old age and that this could be done “for months if not years without needing to increase the dosage.” On the other hand, in the treatment of insanity it is “worse than useless.” He added that cannabis is “by far the most useful medicine in the treatment of almost all illnesses that are accompanied with pain. The professor encouraged the use of cannabis in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia as well as other neuralgic pain; however, in cases of sciatic pain based on movement, the treatment was ineffective. Many patients suffering from migraines were able to overcome the effects of the crisis using cannabis “from the appearance of the first signs or the very beginning of the condition.” As well, cannabis was equally very beneficial in the treatment of “nocturnal cramps in the elderly or in those with gout” and in the treatment of painful menstrual cramps. Some asthmatics suffering from spasticity also found benefit in this treatment.

UNITED STATES

In the United States the use of cannabis for therapeutic purposes was also widespread during the 1800s and early 1900s. In the American pharmacopeia of 1854, its therapeutic properties were described as follows:

Cannabis extract is a powerful narcotic that gives rise to sensations of gaiety, intoxication, hallucinations accompanied by delirium, drowsiness, and mental numbness, with only weak effects on the blood circulation. It also has aphrodisiac properties, stimulates the appetite and, in certain cases, induces a cataleptic state. During organic disorders, it can cause drowsiness, attenuate spasms, relieve nervousness, and reduce the intensity of pain. From the point of view of its effects, cannabis is a little like opium with the difference that it does not suppress the appetite, does not reduce secretions, and does not cause constipation. Its effects are less predictable than those of opium; but in cases where opium is contraindicated because it induces constipation and nausea, then it is better to administer cannabis. It is used specifically to treat neuralgia, gout, tetanus, rabies, epidemic cholera, Huntington’s chorea, hysteria, depression, delirium, and uterine hemorrhaging. Dr. Alexander Christison of Edinburgh attributes to it the effect of accelerating and intensifying contractions during childbirth, and has successfully used it for this purpose. The therapeutic properties of cannabis act rapidly and without any anesthetizing action, even though it seems that this effect is produced in certain cases. (Mikuriya 1973)

It is clear that variations in the chemical composition of the plant contributed to the observation of multiple cases of overdose but without ever producing serious consequences. In his 1912 An Essay on Hasheesh, Victor Robinson wrote, “A strange thing about hasheesh is that an overdose has never produced death in man or the lower animals. Not one authentic case is on record in which Cannabis or any of its preparations destroyed life” (Robinson, 1912, p. 35). In that era, just as today, such a level of therapeutic innocuousness was definitely not the case for other available medications.

In 1938, Robert P. Walton, professor at the medical university in South Carolina, published a treatise titled “Description of the Hashish Experience” (Walton 1938). In it, he provided an account of cannabis intoxication, reported by a young doctor who had intentionally consumed a very strong dose of cannabis.

[After one hour,] quite suddenly there is developed an indescribable feeling of exaltation and of grandeur. The words “fine,” “superfine” and “grand” come to my mind as being applicable to this feeling. This indescribable feeling is purely subjective. . . . The idea of one-ness with all nature and with the entire universe seems to take hold. There is no material body or personality. . . . There is marvelous color imagery, blue, purples and old gold predominating with most delicate shading effects. . . . Evidently sleep gradually set in and continued undisturbed until the usual rising time. No special sensation on rising. Feeling, if anything, more than usually refreshed. All of the sensations recorded above have completely vanished. The recollections of the experiences are however very clear and vivid.

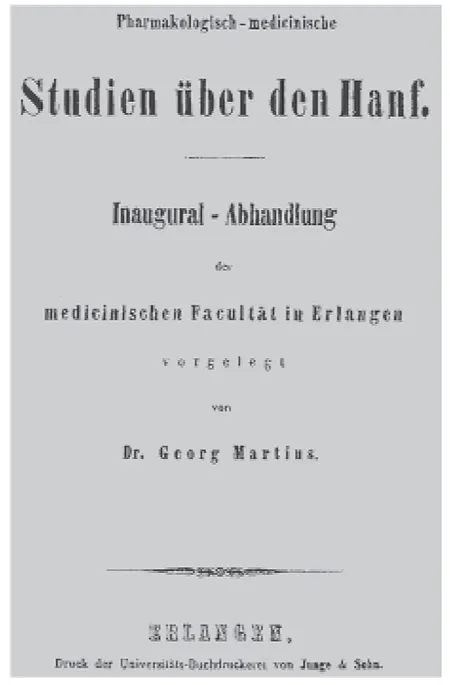

Figure 1.3. First page of the doctoral thesis of Georg Martius d’Erlangen (1855): “I was thinking by the way about hemp, the natural history of which still presents shadowy and erroneous elements, and which in recent years has increasingly attracted the attention of the medical world.”

FRANCE

In France, not only doctors but also artists were interested in the effects of the drug. The poet Théophile Gautier described in detail a long cannabis intoxication in an article in the French magazine Revue des Deux Mondes (Review of the two worlds) in February 1846. The article charted his first experience, in 1843, with the group who later became the Club des Hashischins (Club of the Hashish Eaters). Among the members of this club, which was active from 1844 to 1849, were writers and artists such as Alexandre Dumas (who divulged his experiences with cannabis in his novel The Count of Monte Cristo), Charles Baudelaire, the caricature artist Honoré Da...