- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Why is everything that compromises greatness in art coded as 'feminine'? Has the feminist critique of Art History yet effected real change? With a new preface by Griselda Pollock, this edition of a truly groundbreaking book offers a radical challenge to a women-free Art History.

Parker and Pollock's critique of Art History's sexism leads to expanded, inclusive readings of the art of the past. They demonstrate how the changing historical social realities of gender relations and women artists' translation of gendered conditions into their works provide keys to novel understandings of why we might study the art of the past. They go further to show how such knowledge enables us to understand art by contemporary artists who are women and can contribute to the changing self-perception and creative work of artists today.

In March 2020 Griselda Pollock was awarded the Holberg Prize in recognition of her outstanding contribution to research and her influence on thinking on gender, ideology, art and visual culture worldwide for over 40 years. Old Mistresses was her first major scholarly publication which has become a classic work of feminist art history.

Parker and Pollock's critique of Art History's sexism leads to expanded, inclusive readings of the art of the past. They demonstrate how the changing historical social realities of gender relations and women artists' translation of gendered conditions into their works provide keys to novel understandings of why we might study the art of the past. They go further to show how such knowledge enables us to understand art by contemporary artists who are women and can contribute to the changing self-perception and creative work of artists today.

In March 2020 Griselda Pollock was awarded the Holberg Prize in recognition of her outstanding contribution to research and her influence on thinking on gender, ideology, art and visual culture worldwide for over 40 years. Old Mistresses was her first major scholarly publication which has become a classic work of feminist art history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Old Mistresses by Rozsika Parker,Griselda Pollock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Critical stereotypes

the ‘essential feminine’ or how essential is femininity?

the ‘essential feminine’ or how essential is femininity?

I

When Virginia Woolf was asked to lecture on ‘Women and Fiction’ in 1928 she commented ironically:

A thousand questions at once suggested themselves. But one needed answers, not questions; and an answer was only to be had by consulting the learnèd and unprejudiced, who have removed themselves above the strife of tongue and confusion of body and issued the result of their reasoning and research in books which are to be found in the British Museum. If truth is not to be found in the British Museum, where, I asked myself, picking up a notebook and a pencil, is truth? (A Room of One’s Own (1928), 1974 edn, p. 27)

Hundreds of questions can equally be posed about women in the history of art. Have there been female artists? If so, what have they created? Why did they produce what they did? What factors conditioned their lives and works? What difficulties have women encountered and how did they overcome discrimination, denigration, devaluation, dismissal, in attempting to be an artist in a society which since the Book of Genesis has associated the divine right of creativity with men alone (figs 1 and 2)?

1 And God created Woman in Her own Image, an advertisement for Eiseman Clothing via Michelangelo and Ann Grifalconi (1970) (derived from an original design by Ann Grifalconi)

2 ‘It’s never occurred to you, I suppose, that they could have been created by a cave-woman?’ Cartoon by Leslie Starke, New Yorker, 23 July 1973

The cartoon is a mocking response to feminist art history, which has shown that there have been women artists. We are clearly not meant to take the idea very seriously since the cartoonist has drawn the woman who raises the issue in such a way as to alienate all sympathy or respect.

The cartoon is a mocking response to feminist art history, which has shown that there have been women artists. We are clearly not meant to take the idea very seriously since the cartoonist has drawn the woman who raises the issue in such a way as to alienate all sympathy or respect.

But what answers are to be found on the shelves of the British Museum, that repository of received knowledge? Virginia Woolf was surprised to discover the sheer number of books to consult about women, though written from the assured heights of masculine authority. ‘Are you aware that you are perhaps the most discussed animal in the universe?’, she asked her women readers drily. There is indeed a great wealth of information on women artists in the British Museum. But are the learnèd unprejudiced?

Even a cursory glance at the substantial literature of art history makes us distrust the objectivity with which the past is represented. Closer reading alerts us to the existence of powerful myths about the artist, and the frequent blindness to economic and social factors in the way art is produced, artists are taught, and works of art are received. In the literature of art from the sixteenth century to the present two striking things emerge. The existence of women artists was fully acknowledged until the nineteenth century, but it has only been virtually denied by modern writers. Related to this inconsistent pattern of recognition is the construction and constant reiteration of a fixed categorization—a ‘stereotype’—for all that women artists have done.

To discover the history of women and art is in part to account for the way art history is written. To expose its underlying values, its assumptions, its silences and its prejudices is also to understand that the way women artists are recorded and described is crucial to the definition of art and the artist in our society.

A brief survey of the literature of art up to the nineteenth century shows that the existence of women artists was consistently acknowledged. The sixteenth century artist and critic Giorgio Vasari was one of the earliest writers of art history as we know it. His lengthy study of artists of the Renaissance was a forerunner of the most common genre of modern art history, the monograph, a study of the life and work of an individual artist. In this sixteenth-century text the women artists of the period are both documented and assessed. There is, for example, a chapter on the sculptor Properzia de’ Rossi (1490–1530) (fig. 3), detailed information about Sofonisba Anguissola (1532/5–1625) (fig. 4) and her five sisters, and a description of an ambitious fresco of The Last Supper in the Florentine church of Santa Maria Novella by Plautilla Nelli.

3 Properzia de’ Rossi, Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife, c. 1520

Properzia de’ Rossi was born in Bologna, a city which has a consistent history of progressive attitudes and produced a significant number of women who participated as professionals in many branches of the arts and sciences during the Renaissance (see Laura Ragg, Women Artists of Bologna, 1907).

Properzia de’ Rossi was born in Bologna, a city which has a consistent history of progressive attitudes and produced a significant number of women who participated as professionals in many branches of the arts and sciences during the Renaissance (see Laura Ragg, Women Artists of Bologna, 1907).

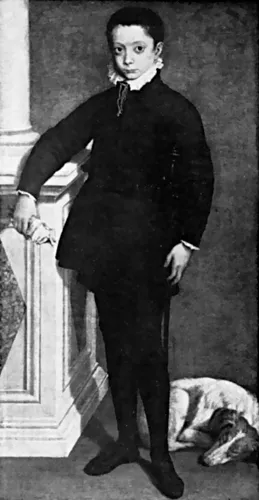

4 Sofonisba Anguissola, Portrait of a Young Nobleman, early 1560s

Anguissola was one of five daughters of a noble family of Cremona. With her second sister Elena she studied under Bernadino Campi and Bernadino Gatti and through her father’s agency was advised by Michelangelo (C. de Tolnay, ‘Sofonisba Anguissola and her Relations with Michelangelo’, Journal of the Walters Art Gallery, vol. V, 1941, pp. 15–18). In 1560 she was invited to Spain by Philip II as a court painter and lady-in-waiting to the Queen. During the twenty years she spent in Spain Anguissola also painted portraits commissioned by the Pope. In 1580 she moved with her new husband to Palermo where she died at an advanced age. In 1624, shortly before her death, she was visited by the Flemish painter, Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), who drew a sketch of Anguissola and wrote in his notebook:

Anguissola was one of five daughters of a noble family of Cremona. With her second sister Elena she studied under Bernadino Campi and Bernadino Gatti and through her father’s agency was advised by Michelangelo (C. de Tolnay, ‘Sofonisba Anguissola and her Relations with Michelangelo’, Journal of the Walters Art Gallery, vol. V, 1941, pp. 15–18). In 1560 she was invited to Spain by Philip II as a court painter and lady-in-waiting to the Queen. During the twenty years she spent in Spain Anguissola also painted portraits commissioned by the Pope. In 1580 she moved with her new husband to Palermo where she died at an advanced age. In 1624, shortly before her death, she was visited by the Flemish painter, Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), who drew a sketch of Anguissola and wrote in his notebook:

Portrait of Signora Sophonisba, painter. Copied from life in Palermo on 12th day of July of the year 1624, when she was 96 years of age, still a good memory, clear sense and kind. . . . While I painted her portrait, she gave me advice as to the light . . . and many more good speeches, as well as telling me parts of her life story, in which one could see that she was a wonderful painter after nature. (Cited in Tufts (1974), p. 20)

The trickle of references to women artists in the sixteenth century grows by the eighteenth century to become a flood in the nineteenth century. Lengthy surveys of women in art from Greece to the modern day were published throughout Europe. There was, for example, Ernst Guhl, Die Frauen in der Kunstgeschichte (1858), Elizabeth Ellet, Women Artists in All Ages and Countries (1859), Ellen Clayton, English Female Artists (1876), Marius Vachon, La Femme dans Part (1893), Walter Sparrow, Women Painters of the World (1905) and the massive compilation of more than one thousand entries on women by Clara Clement in her encyclopedia, Women in the Fine Arts from the 7th Century BC to the 20th Century (1904).

Curiously the works on women artists dwindle away precisely at the moment when women’s social emancipation and increasing education should, in theory, have prompted a greater awareness of women’s participation in all walks of life. With the twentieth century there has been a virtual silence on the subject of the artistic activities of women in the past, broken only by a few works which repeated the findings of the nineteenth century. A glance at the index of any standard contemporary art history text book gives the fallacious impression that women have always been absent from the cultural scene.

Twentieth-century art historians have sources enough to show that women artists have always existed, yet they ignore them. The silence is absolute in such popular works surveying the history of western art as E. H. Gombrich’s Story of Art (1961) or H. W. Janson’s History of Art (1962). Neither mentions women artists at all. The organizers of a 1972 exhibition of the work of women painters, Old Mistresses: Women Artists of the Past, revealed the full implications of that silence:

The title of this exhibition alludes to the unspoken assumption in our language that art is created by men. The reverential term ‘Old Master’ has no meaningful equivalent; when cast in its feminine form, ‘Old Mistress’, the connotation is altogether different, to say the least. (A. Gabhart and E. Broun, Walters Art Gallery Bulletin, vol. 24, no. 7, 1972)

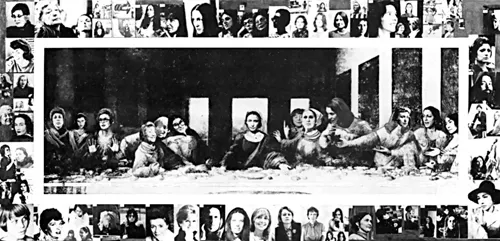

Despite the enormous increase in numbers of women artists during the twentieth century (fig. 5), the assumption persists in our language that art is created by men, an attitude which is perpetuated in contemporary criticism.1 In the Feminist Art Journal (April, 1972), the Tamarind Lithography Workshop published the results of its survey of criticism of contemporary art in major American art magazines. From August 1970 to August 1971, 87.8 per cent of the reviews in Art Forum, a leading art journal, discussed men’s work; only 12.2 per cent reported women’s work; 92 per cent of Art in America’s reviews were devoted to men’s work, 8.0 per cent to women’s work, while men took 95 per cent of the lines allotted to writing on art and 93 per cent of the reproductions. Particular ideological assumptions about women’s relation to art sustain this silence. When one feminist art critic questioned a colleague about his attitude to a woman artist and asked why he had never visited her studio, ‘he said in perfect frankness that she was such a good looking girl that he thought that if he went to the studio it might not be because of her work.’ Another typical example comes from the chairman of an art department who said to a female student ‘You’ll never be an artist, you’ll just have babies’ (The Rip Off File, 1972).

5 Mary Beth Edelson, Some Living American Women Artists, 1972

Dramatis personae at this ‘Last Supper’ (I. to r.): Lynda Benglis, Helen Frankenthaler, June Wayne, Alma Thomas, Lee Krasner, Nancy Graves, Georgia O’Keeffe, Elaine DeKooning, Louise Nevelson, M. C. Richards, Louise Bourgeois, Lila Katzen, Yoko Ono; Guests: (clockwise) Agnes Martin, Joan Mitchell, Grace Hartigan, Yayoi Kusama, Marisol, Alice Neel, Jane Wilson, Judy Chicago, Gladys Nilsson, Betty Parsons, Miriam Schapiro, Lee Bontecou, Sylvia Stone, Chryssa, Suellen Rocca, Carolee Schneeman, Lisette Model, Audrey Flack, Buffie Johnson, Vera Simmons, Helen Pashgian, Susan Lewis Williams, Racelie Strick, Ann McCoy, J. L. Knight, Enid Sanford, Joan Balou, Marta Minujin, Rosemary Wright, Cynthia Bickley, Lawra Gregory, Agnes Denes, Mary Beth Edelson, Irene Siegel, Nancy Grossman, Hannah Wilke, Jennifer Bartlett, Mary Corse, Eleanor Antin, Jane Kaufman, Muriel Castanis, Susan Crile, Anne Ryan, Sue Ann Childress, Patricia Mainardi, Dindga McCannon, Alice Shaddle, Arden Scott, Faith Ringgold, Sharon Brant, Daria Dorsch, Nina Yankowitz, Rachel bas-Cohain, Loretta Dunkelman, Kay Brown, CeRoser, Norma Copley, Martha Edelheit, Jackie Skyles, Barbara Zuker, Susan Williams, Judith Bernstein, Rosemary Mayer, Maud Boltz, Patsy Norvell, Joan Danziger, Minna Citron.

Dramatis personae at this ‘Last Supper’ (I. to r.): Lynda Benglis, Helen Frankenthaler, June Wayne, Alma Thomas, Lee Krasner, Nancy Graves, Georgia O’Keeffe, Elaine DeKooning, Louise Nevelson, M. C. Richards, Louise Bourgeois, Lila Katzen, Yoko Ono; Guests: (clockwise) Agnes Martin, Joan Mitchell, Grace Hartigan, Yayoi Kusama, Marisol, Alice Neel, Jane Wilson, Judy Chicago, Gladys Nilsson, Betty Parsons, Miriam Schapiro, Lee Bontecou, Sylvia Stone, Chryssa, Suellen Rocca, Carolee Schneeman, Lisette Model, Audrey Flack, Buffie Johnson, Vera Simmons, Helen Pashgian, Susan Lewis Williams, Racelie Strick, Ann McCoy, J. L. Knight, Enid Sanford, Joan Balou, Marta Minujin, Rosemary Wright, Cynthia Bickley, Lawra Gregory, Agnes Denes, Mary Beth Edelson, Irene Siegel, Nancy Grossman, Hannah Wilke, Jennifer Bartlett, Mary Corse, Eleanor Antin, Jane Kaufman, Muriel Castanis, Susan Crile, Anne Ryan, Sue Ann Childress, Patricia Mainardi, Dindga McCannon, Alice Shaddle, Arden Scott, Faith Ringgold, Sharon Brant, Daria Dorsch, Nina Yankowitz, Rachel bas-Cohain, Loretta Dunkelman, Kay Brown, CeRoser, Norma Copley, Martha Edelheit, Jackie Skyles, Barbara Zuker, Susan Williams, Judith Bernstein, Rosemary Mayer, Maud Boltz, Patsy Norvell, Joan Danziger, Minna Citron.

At a lecture at the Slade School of Art in 1962, the sculptor Reg Butler proposed a similar identification of women with procreativity and men with cultural creativity:

I am quite sure that the vitality of many female students derives from frustrated maternity, and most of these, on finding the opportunity to settle down and produce children, will no longer experience the passionate discontent sufficient to drive them constantly towards the labours of creation in other ways. Can a woman become a vital creative artist without ceasing to be a woman except for the purposes of a census? (Reg Butler (1962), reprinted in New Society, 31 August 1978, p. 443)

In reviewing an exhibition in 1978 at the Arts Council’s Hayward Gallery in London, organized by women and showing predominantly work by contemporary women artists, John McEwan employed another but related strategy. He identified women not with art, but domestic craft. Only one artist escaped his general censure, but for revealing reasons. She

at least exhibits none of the needle-threading eye and taste for detail that is so peculiarly the bug bear of women artists when left to their own devices; a preoccupation that invariably favours presentation at the expense of content. (John McEwan, ‘Beleaguered’, Spectator, 9 September 1978, our italics)

Such stereotypes and assumptions infect writing on art both past and present. But the denigration of women by historians is concealed behind a rigidly constructed view of art history. Some rationalize their dismissal of women by claiming that they are derivative and therefore insignificant. R. H. Wilenski, for instance, stated categorically, ‘Women painters as everyone knows always imitate the work of some men’ (Introduction to Dutch Art, 1929, p. 93).

But dependence on another is seen as a fault only if stylistic or formal innovation is the exclusive standard of evaluation in art. Lucy Lippard usefully challenges this notion which has so often been used to justify the exclusion of women from serious consideration:

Within the old, ‘progressive’, or ‘evolutionary’ contexts, much women’s art is ‘not innovative’, or ‘retrograde’ (or so I have been told by men since I started writing about women . . .). Some women artists are consciously reacting against avant-gardism and retrenching in aesthetic areas neglected or ignored in the past; others are unaffected by such rebellious motivations but continue to work in personal modes that outwardly resemble varied art styles of the recent past. One of the major questions facing feminist criticism has to be whether stylistic innovation is indeed the only innovation, or whether other aspects of originality have yet to be investigated: ‘Maybe ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Series

- Dedication

- Title

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface to the Bloomsbury Revelations Edition

- A lonely preface (2013)

- Preface (1980)

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Critical stereotypes: the ‘essential feminine’ or how essential is femininity?

- 2 Crafty women and the hierarchy of the arts

- 3 ‘God’s little artist’

- 4 Painted ladies

- 5 Back to the twentieth century: femininity and feminism

- Conclusion

- Longer Notes

- Select bibliography and further reading

- Index

- Copyright