![]()

1 A sociologist’s paradise1

Early family studies (1990–4)

Who’s Looking at the Family?

Richard Billingham first came to the attention of the art world in 1994 when three monochrome photographs of his father were selected for the high-profile survey show Who’s Looking at the Family? at the Barbican Arts Centre in London. Curated by Val Williams (with selectors Brigitte Lardinois and Carol Brown)2 the exhibition had a programme of over thirty-five artists, incorporated rich marginalia of experimental research photography, archive and retrouvé material, and featured established practitioners such as Sally Mann, Larry Sultan, Thomas Struth and Martin Parr (Williams 1994; Warren 2005: 131).

The idea of examining the family in photographic culture was conceived when John Hoole, curator at the Barbican, invited Williams to propose something for the space.3 Social context gave the premise an unanticipated zeitgeist edge. Spanning the mid-1980s to 1994, the exhibition’s frame of reference intersected with the lifecycle of Thatcherism and was organized in the aftermath of the collapse of parliamentary support for the prime minister who had, during her eleven-year premiership (and three election victories), famously advocated traditional family values as a key moral principle of conservative ideology; ironically, however, as is well recognized, the economic paradigm espoused by Thatcher – and that she contrived to establish – generated social conditions that threatened the very survival of the family structure she promoted (Fisher 2009: 32–3).

The critical acclaim Who’s Looking at the Family? acquired can, in this context, be attributed to its perceived response to the way that topics such as ‘child abuse, domestic violence, the growing divorce rate and single parenthood’ were putting the myth of the benevolent patriarchal family core into question (Williams 1994: 14–15). Added to this sociopolitical background, the show’s concept resonated with the argument in Susan Sontag’s influential On Photography (1977) that the nuclear family (what she calls ‘that claustrophobic unit’) subsists today only in brittle images between the leaves of the photo album: ‘Photography’, Sontag declares, ‘becomes a rite of family life just when, in the industrialising countries of Europe and America, the very institution of the family starts undergoing radical surgery’. It is precisely with the obsolescence of the conventional family paradigm that photography starts to function as an ersatz substitute for its lost utopian nucleus (Sontag 1977: 8–9).

The tension is acknowledged in the catalogue essay. With reference to Diane Arbus’s unsettling family portraits for Esquire and the Sunday Times of the late 1960s, Williams invokes the appropriate vocabulary for the pathologization of the family documented in the exhibition: ‘Lost childhoods’ are here ‘remembered, the fears and delights of parenthood minutely examined. Closed doors . . . opened and memories exhumed’ (1994: 15). Tending towards the depiction of a darker, more anxious domestic scenario, the Barbican show, in promoting a heterogeneous palette, sought, at the same time, to pursue a more intimate picture of atypical family life. This ambition is reflected in the diversity of photographic genres encompassed, where documentary approaches are combined with more knowing aesthetic and fictionalizing modes in an effort to establish correspondences among a broad spectrum of image styles, juxtaposing artists like Thomas Ruff, Susan Lipper and Florence Chevallier with less orthodox and amateur footage (the Boorman Family archive) as well as found material and material of unknown provenance.

Born 1970, Billingham was the youngest artist in Who’s Looking at the Family? and at the time was still completing his degree in Fine Art (Painting) at Sunderland University. Most of the other participants were established, mid-career artists, on average twenty years older than him (and capable of testifying to the paradigm shift explored in the exhibition). Accordingly, the curator’s description of his triptych in the catalogue essay (perhaps the very first discussion of Billingham’s art) provides valuable insight into how his work was originally received. Noting a significant incompatibility with typical 1990s style, Williams senses the trace of a ‘more antique’ tradition of image-making in his photography, closer, in its grainy ambiguity, to Edward Curtis, even Nadar, than to Sultan, Parr or Nick Waplington. Although these ‘wistful portraits’ are, she admits, imbued with a ‘certain nobility’, in their almost damaged precarity, they seem haunted by the fragility of existence – by the apparition of a life, she suggests, on ‘the edge of an abyss’ (1994: 44).

Asked why she selected an unknown student’s work for this prestigious international show, Williams answers that, on the recommendation of Michael Collins, then picture editor of the Telegraph Magazine,4 she visited Sunderland to meet Billingham and was immediately convinced of his contribution to the exhibition’s premise.

Indeed, not all organizers were equally convinced of his contribution. Williams remembers that she had to defend his inclusion in the show (Williams 2020, email conversation). ‘It was there that I saw the photos which we eventually exhibited,’ she says. ‘I don’t think they were a triptych at the time – I just put the three together . . . and I thought they would look great in the show’ (Williams 2018). In relation to the theme, Billingham’s ‘allusive’ black-and-white photographs, in this format, ‘worked really well alongside [the more established exponents] because we tried to select work that was about a personal family story rather than just about “the family” and this fitted in with the majority of the other photographers’ (Williams 2018).

The fact that ‘Richard was a student,’ Michael Collins adds, ‘never mattered to me’. As well as suggesting Billingham, Collins was associated with some of the interesting fringe selections of the show such as the Apes of London Zoo project and the Boorman Family archive (both first published in the Telegraph Magazine).6

I would publish and commission students and complete unknowns in the Telegraph Magazine, and when looking at photographs for the first time, I cared not whether they came in a mahogany box, a monograph or wrapped in newspaper.

(Collins 2018)

Self-conscious and slightly intimidated, on the opening night, Billingham worried that his piece was installed in an incongruous way. ‘I stood by my work,’ he remembers, ‘but nobody really looked at it, it was in a place underneath the stairs’ (Billingham 2018). He felt that his triptych seemed disconnected from the central circulation of exhibits: ‘it was a bit of a realisation’, he later recalled, ‘to see so many large, pin sharp images, professionally framed behind glass. My blurry pictures, mounted on board and with a badly written statement, must have seemed a bit out of place’ (Billingham 2013). Despite these reservations, inclusion of his photography in the Barbican show was of enormous significance for the young art-school graduate, and, as we will see, had important consequences for his career.7

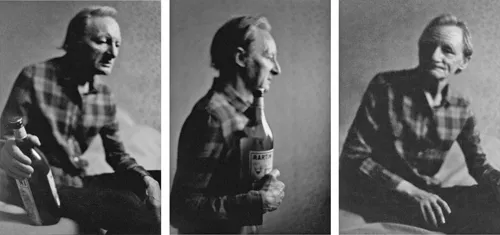

Triptych of Ray (1990)

Coarse-grained and out of focus – indeed scarcely more than a photographic sketch – Triptych of Ray (1990, Fig. 1.1) shows a figure by three, emaciated, toothless, hunched in the half-light, drinking from a catering-size Martini bottle. Torso inclined slightly to the right, thin forearm leaning on thigh, hand dangling limply between knees, he tips the incongruously large bottle towards us.

FIGURE 1.1 Richard Billingham, Triptych of Ray (1990). Black & white photographs on aluminium (160 × 106 cm each).

The bottle is the only distinct detail in an otherwise indistinct scene.

The figure in the central panel has slightly more salience. Seen from the waist up, and in profile, the orientation and rigidity of the form suggest that he has just risen from the bed. He presses the bottle protectively to his chest as if cradling a young child. A whitened thumb-knuckle, and the veins running visibly through the back of his hand, betray the tightness of that grip. Although the bottle, located at the geometric nucleus of the central panel, is undoubtedly the principal motif of the triptych, it is the effect of the contents of that bottle that constitutes the theme of the work. In the right panel, the least clear of the three, the figure is back on the bed again, now without the bottle, in an attitude paralleling the first panel, except in this image, his head is turned back slightly, away from the source of light, looking over his shoulder, surprised, perhaps, by a sound in the room behind him.

Yet, there’s a perceptible sequential decrease in distinctness which has the effect of making the frail figure appear to diminish visibly – literally fading before our eyes or merging gradually with his grisaille surroundings – as we scan the three images. Unused to this level of opacity in the trompe l’oeil realism of straight photographic space, its primary effect in this instance is to emphasize the impressionistic, painterly qualities of the work: if the blur-speck interference serves to draw attention to the optical surface of the print, disrupting and undermining the condition of ‘photographic transparency’ (Lopes 2003) with a grainy sfumato, and inhibiting visual resolution, these are, paradoxically, the precise qualities that tend to amplify the work’s aesthetic qualities, imbuing the event with a rich and ambiguous relationship of pattern, surface and depth that appeals primarily to a tactile (rather than an optical) modality.

These atmospheric effects are responsible for the lyrical quality of the piece. Reminiscent of Denise Colomb’s vaguely macabre asylum portraits of French dramatist Antonin Artaud taken in 1947, Billingham registers some indistinct yet intense state in his subject, a moment of internalized privacy, something that remains inscrutable, a heightened mood that, even if ultimately ineffable, is nevertheless rendered in some manner ‘precise’. Words like loneliness, ennui or apathy seem inadequate to characterize this elusive state; perhaps this is because, at a deeper level – reminiscent of Edward Hopper’s evocative etchings of the 1920s, the plays of Samuel Beckett or Francesca Woodman’s convulsive self-portraits – Billingham’s early photographs of his father, in which he’s reduced to a pale ghostlike form in the dwindling light of evening, evoke something more profound and existential, that condition perhaps of ‘quiet desperation’ that Henry David Thoreau identified as the silent and solitary condition of lives in modern society (Thoreau 1995: 4). Then again, the inscrutable look could just be the desensitizing effects of the alcohol.

Inclusion of Billingham in Who’s Looking at the Family? had the effect of inscribing the artist into a prototypically British neorealist visual paradigm that includes Martin Parr, Daniel Meadows, Chris Killip, Nancy Hellebrand, Paul Graham, Shirley Baker, Keith Pattison and, most significantly perhaps, Bill Brandt, whose (then) newly rediscovered documentary photographs of working-class family life in the tenements of Birmingham (commissioned by the Bournville Village Trust during the Second World War) were exhibited in Birmingham Central Library in 1990.

In their stark formal austerity, it is tempting to regard Brandt’s documentary photographs as iconographic, if not (at the very least) geopolitical, antecedents of Billingham’s aesthetic.8 In that they also double as artistically compelling interior studies of period kitchen scenes, domestic work, bedrooms, Brandt seems a plausible influence (James and Sadler 2004). This, however, is not as obvious as it may appear. Billingham insists that, although he was in college in Birmingham at the time, he never saw Brandt’s exhibition ‘or any other photography [while] on foundation’.9 We must therefore exercise caution from the outset regarding what may appear to be leading photographic references in the effort to thematize Billingham’s work. Although it may be tempting to contextualize Billingham’s early photographs with reference to canonical British social realist or documentary photographic practice, it is also necessary to r...