![]()

Part One

The Arts of Reproduction

![]()

1

A Bug for Photography? Hippolyte Fizeau’s Photographic Engraving and Other Media of Reproduction

Stephen C. Pinson

In 1936, the New York Public Library (NYPL) acquired a collection of books and images that once belonged to the French physicist Armand-Louis-Hippolyte Fizeau (1819–96).1 Generally recognized today for measuring the speed of light, Fizeau was also at the centre of a group of early photographic innovators with whom he exchanged letters, publications, photographs and trial proofs from experimental processes. Counted among the collection are examples of some of the most prized material from photography’s early history, including calotypes by William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–77) and a signed copy of the first fascicle of his The Pencil of Nature (1844), considered to be the first photographically illustrated book published for sale. Less well known is a group of about fifty prints, the majority of which were made using a process developed by Fizeau to etch and print from daguerreotypes by transforming the silvered copper plate into a printing matrix. Owing to their hybrid status as ink-based photographic reproductions, these printed incunabula have had little purchase in most accounts of photography’s intersection with modern art. Unlike photographs derived from negatives—which are often viewed as ‘original’ despite existing as multiples—these works did not benefit from photography’s assimilation into the history of art after the medium’s entrance into museums and newly created art divisions within libraries during the twentieth century.2 Nor did they serve as evidence to debunk modernism’s claims to originality, a tactic complicated by the supposed uniqueness of the daguerreotype. As a result, Fizeau’s process and other early attempts to reproduce daguerreotypes were left as technical footnotes in most histories of photography, in which Fizeau is best known for his contributions to Excursions daguerriennes (1840–4), the extensive publication masterminded by the optician and publisher Noël Paymal Lerebours (1807–73), featuring graphic engravings after topographical daguerreotypes.3 But the truth is that even in the 1840s, Fizeau’s work would not have fit easily into any narrowly defined concept of reproduction, a term that had only recently been applied to photography.

As late as 1835, the dictionary of the French Academy only used the word reproduction in its original sense of regeneration or procreation, as borrowed from the field of biology.4 Within five years, however, it had been extended to photography and other industrial processes used to create multiple, identical products. As Henri Zerner cautions, ‘Reproduction functions less as a true concept than as a nebulous semantic field, the multiple and sometimes contradictory connotations of which can work for or against the elevation of the status of photography within the cultural values of the time.’5 In this sense, reproduction was part of what Zerner calls an ‘unstable vocabulary’, including many neologisms, which marked photography’s first decade by an attempt to specify the new invention coupled with a ‘more natural tendency to view the unknown in terms of the known’.6 Taking this notion of reproduction as a methodological starting point, this chapter offers a reassessment of Fizeau’s images within the visual economy of the early nineteenth century. Just as Fizeau found himself at the centre of a multidisciplinary network, his reproductions intersected with the nascent fields of photography, electricity and entomology, domains which had more in common than our current histories have allowed.

Specimens

The sales catalogue summary of the London dealer E.P. Goldschmidt, from whom the NYPL purchased the Fizeau collection, describes the various ‘specimens of early portraits [and] daguerreotype prints’ as ‘quite rare indeed’.7 My research shows that the perceived rarity of these works is directly related to the fact that they have remained, until now, largely unexplored (with most of the subjects still unidentified) whereas their actual rarity is relative.8 The NYPL appears to hold the largest trove of Fizeau’s work, followed by the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers in Paris and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles; there are also examples scattered among private collectors and across several other institutions internationally.9 Several of the NYPL’s photographic engravings exist in multiple states—some of which Fizeau accordingly inscribed in ink ‘1ere’ [sic] and ‘2eme’ [sic]—indicating that they are the first and second states of trial proofs (Figures 1.1 and 1.2). A closer look at these works reveals important clues about their production, including hallmarks (symbols engraved or stamped into the plates with potential information about silver content and/or manufacturer) and printing techniques.

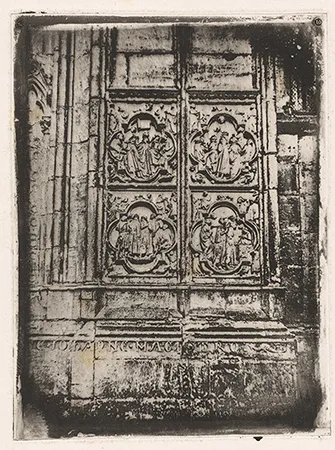

Figure 1.1 Hippolyte Fizeau and Noël Paymal Lerebours, Virtues, bas-relief from Notre-Dame de Paris (first state), 1841–4, photographic engraving. Image: 4 3/16 × 3 in (10.6 × 7.6 cm). The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library (106PH1349.026). Reproduced with the permission of The New York Public Library. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/11653420-1e64-0137-4337-653b444e2651.

Figure 1.2 Hippolyte Fizeau and Noël Paymal Lerebours, Virtues, bas-relief from Notre-Dame de Paris (second state), 1841–4, photographic engraving. Image: 4 3/16 × 3 in (10.6 × 7.6 cm). The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library (106PH1349.027). Reproduced with the permission of The New York Public Library. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/12398bb0-1e64-0137-0097-5732a5866d48.

Although there is still no definitive catalogue of daguerreotype hallmarks, the available sources indicate that two of the printed marks on the NYPL material (a sexpartite rosette and the letters ‘HS’) appear on daguerreotype plates as early as 1843, when Fizeau first showed examples of his photographic engravings at a meeting of the Académie des Sciences in Paris and the year before he patented the process.10 The numeral ‘10’ that appears in the corners of many of the photographic engravings indicates the ratio of silver to copper (1–10) which is in fact high for daguerreotypes, the more common ratio being 1–40. The number is important, however, because Fizeau recommended the 1/10th ratio for his process.11 Such details, which have long been the basis of print connoisseurship, are often neglected or absent in studies of early photography, particularly when it comes to hybrid media such as photo-engravings. Yet, as in this case, they often help ascertain or confirm production date, support attribution and provide context for specific techniques. For example, slight variations in the different states of the same printed image are related to the fact that Fizeau printed them from a single plate he had etched at different depths and/or from various states of the daguerreotypes that he electroplated as part of his photographic engraving process.12 See, for example, the more nuanced shading and greater degree of detail visible in the second state of the trial proof introduced above (Figure 1.2).

Fizeau’s experiments followed the realization by Moritz von Jacobi (1801–74) in 1838 that electroplating—the deposit of metal that occurred on copper plates through chemically produced electricity—had endless applications, from printing to the reproduction of industrial objects and art.13 Fizeau appears to have been the first researcher to apply the process to daguerreotypes, making copies from originals throughout the spring of 1841 in advance of attempting photographic engraving.14 The latter process is complex, but Fizeau essentially used an acid-etched daguerreotype plate as one pole of a battery onto which he first electroplated a layer of gold and then a final layer of copper, thereby making the plate thicker and increasing the depth at which it could be etched and, consequently, the number of impressions that could be made. Lerebours purchased the rights to Fizeau’s patent in France, and the Swiss engraver Johann Hurlimann (1793–1850) oversaw the printing of the plates. Lerebours’s surname (having first been engraved on the daguerreotype plates) appears in reverse on many of the NYPL’s photographic engravings, and Hurlimann is the only named sitter among the fourteen portraits in Fizeau’s collection at the NYPL.15

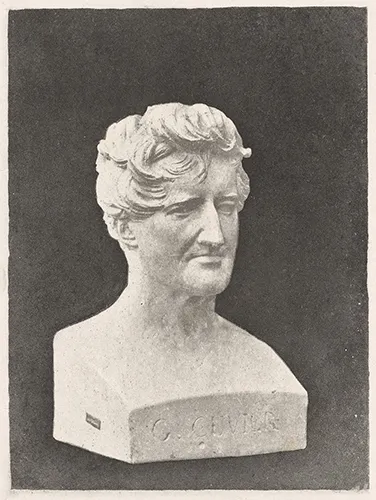

The subjects of Fizeau’s photographic engravings that I have been able to identify comprise, in addition to portraits, reproductive engravings after paintings, including one by Jean Louis Roullet (1645–99) after The Virgin of the Grapes by Pierre Mignard (1612–95), and the infamous engraving by Paolo Mercuri (1804–84) after the 1831 Salon painting, Arrival of the Harvesters in the Pontine Marshes, by Léopold Robert (1794–1835).16 There are also architectural details and reproductions of sculpture, including bas-reliefs from Notre Dame cathedral [the fourteenth-century Funeral of the Virgin from the choir of the north façade (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2), and the thirteenth-century Virtues from the south transept]; a statue of the Immaculate Conception, complete with a serpent at the feet of Mary, who is crowned with stars; and a plaster copy (Figure 1.3) of David d’Anger’s 1833 bust of the naturalist Georges Cuvier (1769–1832).17 Other subjects that might be called ‘scientific’ include a barometer designed by Lerebours, a trial proof printed from a daguerreotype micrograph likely made for Alfred Donné’s Cours de microscopie (1845) and an enlargement of a bug, to which we will return (Figure 1.4).18 This hodgepodge of subject matter was typical of early attempts at photomechanical reproduction, which included prints aimed at an audience of artists, scientists and the publishing industry. Fizeau was relying upon a selection of available daguerreotypes made within a narrow network of enthusiasts (mostly drawn from the same audience) whose production was spurred on by professional competition.19

Figure 1.3 Hippolyte Fizeau and Noël Paymal Lerebours, Bust of Georges Cuvier, after David d’Angers, 1841–4, photographic engraving. Image: 3 3⁄4 × 2 13⁄16 in (9.5 × 7.1 cm). The Miriam and Ira D. ...