![]()

1

THE ABJECT EROTIC FEMININE IN HANS BALDUNG GRIEN

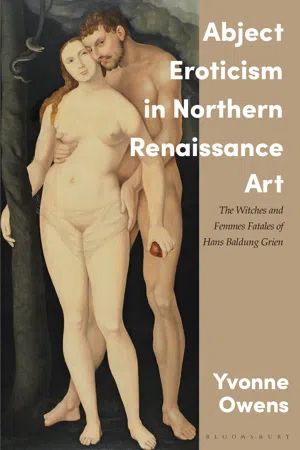

In 2007, the Städel Museum presented ‘Witches’ Lust and the Fall of Man: the Strange Fantasies of Hans Baldung Grien’. Curated and documented by Bodo Brinkmann, the show exhibited Baldung’s Witches’ Sabbath works alongside his ‘Fall of Man’ themed images.1 This juxtaposition gave an overwhelming impression of the threatening allure with which Baldung imbued his graphic, nude representations of the dangerous, eroticized, feminine body. For the sixteenth-century Northern humanists who were the primary clients and collectors for these works, it seems that erotica must be accompanied by the implicit, deeply affective threat of imminent physical and moral danger. Positing the womb as a kind of ‘Pandora’s box’,2 classical and medieval antifeminist tropes fed into a coherent, elite discourse of the seductions and pollutions of witchcraft being firmly rooted in phlegmatic, feminine physiology. One image among Baldung’s idiosyncratic oeuvre stands out, however, as embodying a stunning range of discourses, emblems and tropes informing Renaissance ideas around toxic, feminine physiology and Woman’s ‘natural’ ability to inflict her fatal ‘witchcraft’ through sex. The youthful woman of a highlighted pen and ink drawing created in 1515, most often recognized by the title of the Witch and Dragon (Figure I.1), presents a comprehensive ‘buffet’ of sixteenth-century medical and theological figures informing the idea of the dangerous, female, sexual ingénue. Just setting out on her nefarious career as seductive enchantress and horrific nemesis, the adolescent ‘witch’ in this image represents the quintessential siren, irresistibly calling men’s virtue to its demise.

Sourcing Baldung’s Witch and Dragon

What do we actually see when viewing the Witch and Dragon, and what cultural and epistemological conditions enabled its educated, ‘safe’ reading by its select, erudite audience? The individual elements of the Witch and Dragon are shocking and not easily comprehended. Combined into the total picture, they coalesce into an utterly mystifying tableau of sexual mischief. Just what this mischief consists of is left relatively unexplained to modern sensibilities, for there is little about this picture that is obvious to the contemporary viewer. To the contemporaneous collector of such works, however, we must assume that the iconic elements were transparent and easily accessed and that, incorporated into the picture’s combined, textual message, they formed a coherent whole. This intricate, complex range of correspondences and signifiers is what likely supplied the greatest pleasure to the audience for Baldung’s witch images, perhaps even surpassing their erotic value or their elite exclusivity.

The work is a chiaroscuro drawing, executed in pen and ink and grey wash on primed, coloured paper shaded a dark taupe. Details are highlighted in white and black ink, with lines of exquisite fineness and delicacy at odds with the brutish eroticism of the image. At 293/297 × 207 mm, the piece is not large, but it delivers a powerful impact to the eye, and to the mind, which reels in attempting to make sense of the pictured tableaux. Item by item, then, of what species of iconography does this particularly abject, erotic image consist? There is, central to the composition, a beautiful, nude, very young woman. She is pictured bending over slightly, presenting her back and her full, shapely buttocks, while looking over her shoulder in the direction of the viewer. We can see her face, thereby, and her gestural pose is contorted in such a way as to reveal the finely detailed labia of the sexual orifice nestled between the lobes of her derriere. The small of her back is bunched and muscular, more crudely cross-hatched than the other figurative contours, giving a bestial impression. She arches her back and extends her buttocks in the direction of the gaping maw of the dragon that crouches on the ground behind her. Like the dragon, she also contorts her body in a slight crouch, enabling the release of an unidentifiable vaginal emission in a steady stream into the dragon’s mouth from between the exquisitely rendered vulva lips (schamlippen).

The young woman’s delicate facial features are, like her vulva, very finely rendered. So is her long, curly hair, the locks of which coil skyward as if electrified. An invisible force, like a static wind, appears to lift the tendrils of hair, just as it levitates the unidentifiable smoke or vapour emanating from the weird, cervical opening at the end of the reptile’s tail. Baldung awards coiling, serpentine tresses to most of his female subjects, even to female saints, but the hair of this witch seems especially unmanageable. As if possessed of a self-willed, threatening animus like the monstrous serpents of the Medusa’s pate, it roams off in all directions, independent of wind or motion, obeying some inner, iniquitous promptings. The hands and fingers are exquisitely detailed, with highlighting showing off their sensual contours. The limbs, curves and rounded forms of the adolescent witch’s body are all finely highlighted in white ink with extremely sensitive cross-hatching, as are the twisting coils of the dragon, his fins, frills and the strange orifice at the terminus of his tail. The creature appears both phallic and uterine in conformation. Both bulbous and tubular, its ambiguous relationship to the woman’s uterine efflux is also ambivalently communicated in the drawing. ‘He’ is not actually identifiable as masculine but seems more androgynous or hermaphroditic – an abominable, liminal beast.

Two putti disport themselves in the lower half of the composition, one – looking like a toddler of one or two years – straddles the dragon’s serpentine form just behind its head, while teasing it, and forces the reptilian mouth open by sticking two pudgy fingers inside its nose. The other – appearing as an infant of several months of age – supports the ouroboros formed by the curl of the creature’s tail between two chubby hands while kneeling on the ground. The young woman/witch wields a sort of leafy, vegetal wand, inserting its long shaft between the large, detailed labia of the strange, aforementioned orifice located at the nether tip of the dragon’s tail. The cervix-like, gaping orifices at both ends sport carefully rendered ‘lips’. The rear aperture emits a stream more obviously igneous, vaporous or gaseous than that issuing from between the witch’s legs. It rises skyward like the witch’s animated hair, creating a kind of polluted, elemental symmetry.

On its reddish-brown ground, resembling the stain of dried blood, with mysterious streams and smokes descending and ascending, Baldung’s Witch and Dragon appears to speak directly to prevailing tropes surrounding menstruation, the monstrous conceptions and elemental disordering constructed as resulting from ungoverned, feminine maleficium. The adolescent girl of Baldung’s imagining is perhaps a young witch just starting out, undergoing menarche (‘The Curse of Eve’) and its attendant, mortifying contract with the ‘evil spirit’. The two obscenely contorted bodies are locked in a symbiotic circuit, the overall impression being one of ‘hot’, charged, vertiginous interactions of an unspecified, but definitely impure, nature. It has been conjectured that the form linking the creature’s mouth and the witch’s sex denotes the dragon’s tongue,3 or that the fiery stream actually originates in the dragon’s maw and is being directed into the witch’s sex as a form of demonic sexual congress.4 This reading of the streaming form seems unfounded as the creature’s tongue is clearly visible beneath it, and the directional flow of the stream would seem to originate with the witch, as it is narrower at the point of bodily exit and widens as it descends into the dragon’s mouth. It would even be possible to interpret the streaming form as umbilical cord tissue, implying that a newborn infant had been ‘sacrificed’ to the demonic reptile. The idea that the stream simply and straightforwardly represents feminine blood, however, combines more readily available abject signifiers for the early modern imagination than these other contestants.

Linda Hults speculated that the drawing represented ‘a brilliantly conceived dirty joke that must have been intended for the eyes of Baldung’s male friends’.5 It was during his time in Freiburg, while working on the cathedral’s high altar, that some of Baldung’s most iconic witchcraft figures were created, including the Witch and Dragon.6 These were widely circulated among artists and humanists, and then copied, ultimately destined for various prestigious cabinet collections. ‘At its deepest level, the Karlsruhe drawing is a concise and penetrating interpretation of the witchcraft theme and an expression of the thoroughgoing misogyny of the sixteenth century.’7 The provenance of this iconic work is uncertain. It is currently held in the Karlsruhe Kupferstichkabinett. The cornerstone of the collection (which now spans some 100,000 sheets) was successively laid by the margraves and later grand dukes of Baden, including drawings and prints by German masters of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods, especially those active in the Upper Rhine. Foremost among these masters were Martin Schongauer (c. 1450/53–91), Matthias Grünewald (c. 1470–1528), Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) and Hans Baldung Grien (c. 1484/85–1545). The collection actually began with some of Baldung’s earliest works, he having been patronized early in his career by the dynasty of the Margraves of Baden-Durlach in Basle, with Christopher I as one of Baldung’s most loyal patrons.8 He commissioned the young Baldung to paint the Markgrafentafel, or ‘Margrave panel’, sometime between 1509 and 1512.9

One of the great-grandsons of Christopher I, Margrave Frederick V of Baden-Durlach (1594–1659), an avid collector of prints and drawings, is known to have acquired a sketchbook of Hans Baldung, and a large collection of drawings, during a trip to Strasbourg.10 Although there is no date for this, nor any precise record as proof, it is probable that the Witch and Dragon came into the collection at this point. If so, it is possible that the drawing resided in the so-called ‘Nudities Room’ of the Kunstkammer, a cabinet of art and curiosities, at the court of the Margraves of Baden-Durlach. An elite, luxury cabinet collection would have been the natural home for such a work. The contents of cabinet collections typically consisted of small or miniature, erotically charged, precious works of art for private viewing and discussion.11 Two works by Baldung are known to have been a part of the margraves’ Kunstkammer prior to 1688, although these were described as bath scenes.12

The association of women with monsters and monstrousness extends back at least as far as Aristotle, who postulated the human norm in terms of bodily organization based on the male paradigm in his Generation of Animals.13 The female form is an anomaly, according to this model, a variation on the main theme of mankind that only happens when and if something goes wrong or is defective (or deficient) in the reproductive process. The topos of women as a sign of abnormality or ‘deformed male’ props up the derivative topos of difference as a mark of inferiority, which remains a constant in Western scientific discourse.14 One of the by-products this association has produced is the misogynistic literary genre of antifeminist satire, which trades upon abjection and horror of the female body. This imagistic ‘code’ made use of the kinds of intensely sexualized, scatological imagery parlayed by the ancient, misogynist satirists, newly minted examples of which were rolling off the major printing presses, in the North and in Italy, during the years of Baldung’s artistic production.15 Misogynist satires by authors such as Lucian (c. 125 – after 180), Juvenal (thought to have been active in the late first and early second centuries), Ovid (43 BCE–17 CE), Virgil (70–19 BCE) and Tertullian (c. 155–c. 240) and vernacular works by their medieval emulators, such as, Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–75), Walter Map (1140–c. 1210) and Jean de Meun (c. 1240–c. 1305) were equally popular with the humanist literati, delivering up misogynistic representations of women and their perversely inferior bodies for ridicule. Juvenal, particularly, includes many of the more damning misogynistic themes prominent in antifeminist literature, like female disorder, drunkenness, sexual promiscuity and, notably, woman’s reversal of the natural order as a domina who wants to ‘enslave, belittle, and enfeeble her male partner’.16 These works provided models for an archly satirical approach in literature and art.

The prominent humanist and alderman of Nuremberg Willibald Pirckheimer (1470–1530) employed similar stylistic conventions in mentoring his protégée, Albrecht Dürer. Pirckheimer, like Baldung, was the son of a university-educated lawyer in the employ of a bishop (of Eichstatt) and had also been brought up and educated in the humanist tradition. By virtue of his talent and close friendship with Pirckheimer, Dürer was ushered into his mentor’s elite humanist circles.17 Tutoring and advising Dürer in the humanist discourses, topics, treatments and themes circulating among his elite milieu, Pirckheimer collaborated with the artist on his most prestigious commissions and projects, availing his pupil of the import of Latin texts and enabling the artist to knowledgeably render elite subject matter with the expected formal conventions, protocols and treatments.18 This advice included consultation on compositions, border motifs, classical embellishments, choice subjects and motifs. Pirckheimer was a close collaborator on the Triumphal Arch (published 1517–18) and the Great Triumphal Chariot, with Peutinger and Johann Stabius, commissioned by Maximilian I.19 Pirckheimer’s milieu included the German nationalist ‘arch humanist’ Conrad Celtis, with whom the artist conferred through Pirckheimer and formed close ties in their respective literary and artistic publishing schemes for the millennial date of 1500.20 Dürer’s convention of signing his name with his monograph in Latin (using the word faciebat instead of the contemporaneous fashion of using fecit) was inspired by Pirckheimer’s resuscitation of the ancient practice recorded by Pliny.21

Pirkehimer communicated with his pupil through a lengthy, well-documented, archly scatological letter correspondence, and it is likely that the attitudinal ‘climate’ of classical, misogynistic satire also invested the culture of Baldung’s tutelary atelier.22 Stylistically, the satirical text is, itself, inherently monstrous and affords an expression of a degree of monstrousness that might shock in other literary genres.23 In the Witch and Dragon, with its strange, foaming stream of foully ingested efflux, Baldung may be seen to have mediated visually what Boccaccio contributed to early humanis...