![]()

‘Silent Running’

Running silent in my dreams …

According to Bruce Dern, it’s all about the watering can.

Looking back on Silent Running at the turn of the twenty-first century (about the same time that the vast Valley Forge spaceship would have been setting out on its eight-year mission), Dern reflected on the number of people who have spoken passionately to him about the film’s final scene in which a lonely Drone, Dewey, is seen tending to his interstellar garden – a child’s watering can held gently but firmly in his mechanical hand. ‘They can never remember where or when they first saw the movie,’ Dern observed, ‘but they can never forget that scene.’

In my case, Dern is half-right. Like so many of the film’s fans, I too am transfixed by that haunting image, which has been with me for more than forty years. Indeed, as I write this, I am accompanied at my desktop by a tiny but precise model of Dewey, watering can in hand, alongside his companions Huey and Louie – delicately fashioned figurines given to me by a friend who knew how much the movie meant to me. Yet unlike those devotees mentioned by Dern, I can remember exactly where and when I first saw Silent Running.

It was October 1972, and I was an impressionable nine-year-old on a trip up to London’s West End with my great school-friend Mark Fürst and his father, János, a music conductor of renown. Neither Mark nor I knew anything about the film we were about to watch, but we had been assured by Mr Fürst that it would be right up our street. Arriving at the London Casino Cinerama in Old Compton Street, we were greeted by a dramatic, angular poster boasting dome-like spaceships, interplanetary vistas, and futuristic robots which convinced us that we were indeed in for a treat. Inside the cinema, I found my view of the magnificent 64ft x 24ft louvred screen partially obscured by the head of the person sitting in front of me, and I had to lean out into the aisle to see the film properly – something which left me with a fearsome crick in my neck.

Before the main feature, a trailer for a revival presentation of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) whetted our appetites for space-travel adventure, with its bold vistas and striking musical cues enhanced by the magnificent surroundings of the cinema. An accompanying B-feature followed, a documentary about the art of stunt men which I initially mistook for the main presentation, its opening shot showing a man and a woman running dramatically across a burning airfield. Finally, the feature itself started, and I gazed up in wonder as what would become my favourite science-fiction movie of all time unspooled before me in glorious 70mm …

That night, I lay in bed and wept, my heart broken by the melancholy nature of Silent Running’s overwhelming denouement for which I was utterly unprepared. Unable to shake myself free from the movie’s powerful spell, I demanded to be taken back to the cinema to see the film again, desperate to get back on board the Valley Forge in the company of what the poster proudly called ‘amazing companions on an incredible adventure … that journeys beyond imagination!’ As far as I remember, I saw Silent Running three times at the Casino, and several more when it finally found its way into the wilds of the London suburb in which I lived.

Over the years and decades that passed, I would become an obsessive collector of all and any memorabilia associated with Silent Running. Posters, press books and stills were filed alongside magazine articles and soundtrack albums, T-shirts and models. For my fiftieth birthday, a friend from Cornwall gave me a beautiful piece crafted by local artist Rob Carter in which Freeman Lowell and his two companion Drones were fashioned from painted clothes pegs – an item which now takes pride of place on my wall, next to my signed copy of the original UK release poster. Meanwhile, Huey, Dewey and Louie look on, variously holding a spade, a hand of cards and a watering can, their presence a constant source of both sadness and joy.

Models, clothes pegs and soundtrack album

To be clear: Silent Running is not a film about which I can be dispassionate. Having lived for so many years in the company of its characters, its music, its legacy, I have long since parted company with anything approaching critical distance. After The Exorcist (1973), it is the film which I have viewed more times than any other – probably fifty or sixty, quite possibly more. Over the decades, I have bored my friends with tales of my love of the film, arranged scratchy 35mm screenings of it in both England and Northern Ireland, and even presented selections from its original score on stage with a full orchestra. As a battle-hardened critic, I accept that some of the film’s appeal is tied up with my own nostalgic memories of that first viewing in October 1972, and the impact which the film had upon me as a child. Yet over the years, I have met enough people who have had exactly the same response to Silent Running to know that my reaction is by no means unique. On the contrary, the strange community of those who have been touched by Douglas Trumbull’s enduring masterpiece continues to expand. Far from withering with age, Silent Running has grown in stature as the years have fallen away, flowering like the budding plants so carefully nurtured by Dewey. Look around you and you will see its ghosts everywhere – nowhere more so than in the title character of Disney/Pixar’s Wall-E (2008), a wombling robot beloved of the children of the twenty-first century, who is clearly a modern-day descendant of the Drones of Silent Running.

Today, Trumbull’s vision seems more forward-looking than ever, a blueprint which continues to be mirrored and imitated by film-makers. For me, the movie still looks as captivating, as enchanting and as heartbreaking is it did on that unforgettable evening back in October 1972. As Bruce Dern says of the film’s final image, ‘Dewey’s still out there …’

* * *

‘You don’t think that it’s time that somebody cared enough to have a dream?’

Although it may be set in the ‘future’ (at the time of its creation, the year 2008 was but a distant horizon), Silent Running is very firmly rooted in the past – specifically in the counter-cultural upheavals of the late 1960s, and the legacy of the Vietnam War. In financial terms, the film owes its existence to Easy Rider, Dennis Hopper’s low-budget 1969 biker movie which scored big with its youth audience, causing studios to rethink their business models in an age of costly flops. With an eye on this demographic, studio executive Ned Tanen (who would later become president of Universal’s film division) decided to try an experiment – to finance a string of comparatively low-budget features with ‘counter-culture’ credentials over which the studio would exert little or no creative control. The experiment reaped mixed results (both artistically and financially), with Hopper’s The Last Movie (1971), Peter Fonda’s The Hired Hand (1971), Milos Forman’s Taking Off (1971) and (most successfully) George Lucas’s American Graffiti (1973) all variously benefiting from Tanen’s adventurous patronage. The rules were fairly simple, with a strict $1 million budget limit being the quid pro quo of unprecedented artistic freedom and the promise of final cut. It was within this framework that aspiring film-maker Douglas Trumbull cut his directorial teeth, working in an environment in which the studio resolved ‘not to interfere with production at all, just to let some young film-makers have their head and see what happens’. The circumstances seemed perfect, yet Trumbull insisted at the time (in on-set footage shot during the making of the film) that

I was never planning on directing this picture. I wanted to conceive of the picture, but I didn’t know anything about directing. But then we realised that there didn’t seem to be anybody around who was a confident director capable of doing what I wanted to do. So I really ended up directing by default, in that nobody could think of anybody else to handle this crazy picture.

Trumbull, who was twenty-nine when he directed Silent Running, had a background in special effects. The son of a commercial artist and an engineer, he had grown up believing that a future in architecture awaited. Yet a long-standing interest in science-fiction cinema and literature, matched by a skill in photorealist airbrush illustration, soon sidetracked Trumbull into film-making. Having secured a position in the early 1960s at Graphic Films, which had contracts with NASA and the US Air Force, Trumbull found himself doing pre-visualisation work for the Apollo programme, producing lifelike ‘lunar landers and vertical assembly buildings’ for use in research, development and education.

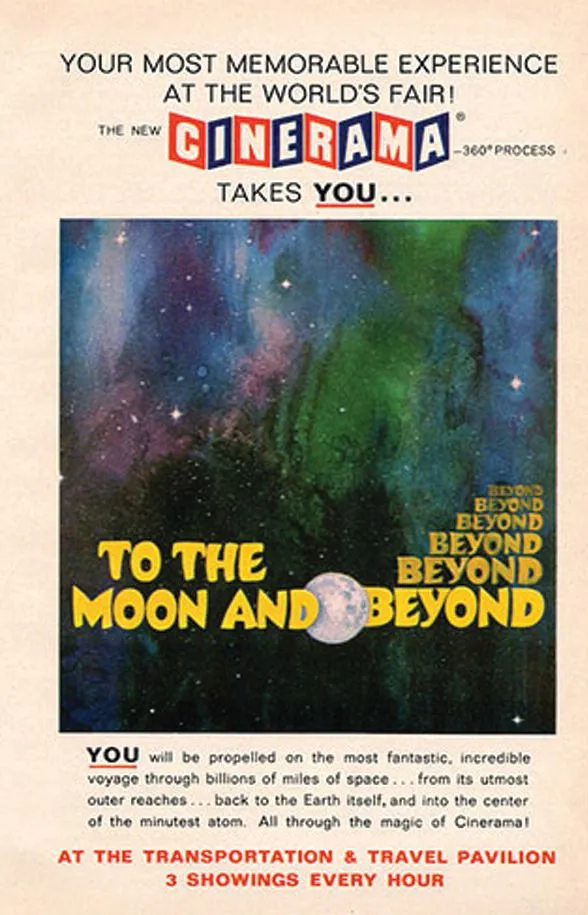

In 1964, he worked on To the Moon and Beyond, a Cinerama-360 film created for the World’s Fair which was projected onto the giant ‘Moon Dome’ screen, with stunning results. ‘I produced a lot of the artwork for the multi-plane and fish-eye photography,’ Trumbull told Debra Kaufman in 2011. ‘The movie was a trip to the moon and it became very abstract at the end.’1 Viewed by director Stanley Kubrick and writer Arthur C. Clarke, To the Moon and Beyond acted as a calling card which Trumbull used to get a job developing animations for their long gestating project Journey Beyond the Stars, which would eventually be retitled 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Originally enlisted to produce the computer graphics seen on the monitors and data display screens within the Aries moon shuttle, Trumbull soon became one of four special photographic effects supervisors on the film, his role expanding as Kubrick encouraged him to experiment with the limits of special-effects photography. Trumbull rose to the challenge, most notably as the driving force behind the slit-scan photography process which produced the dazzling Star Gate finale that remains the film’s most controversially memorable sequence. Despite urging Trumbull to reach ever further in his pursuit of ‘The Ultimate Trip’, however, Kubrick remained fiercely possessive about taking credit for the film’s eye-boggling visuals, insisting upon the single-screen credit ‘Special Photographic Effects designed and directed by Stanley Kubrick’, which ensured that the film’s Academy Award was received by him and him alone (Trumbull, Wally Veevers, Con Pederson and Tom Howard each receive a single card credit as Special Photographic Effects Supervisor).

One result of this was to convince Trumbull that he needed to work for himself rather than for somebody else, although upon returning to Los Angeles he promptly underbid for special-effects work on Robert Wise’s The Andromeda Strain (1971), a move which nearly bankrupted the fledgling company he had formed in the wake of 2001. Yet being in London for so long had had one very significant positive effect on Trumbull’s life; it had kept him out of the reach of the draft for service in the Vietnam War which became the source of such fervent protest and domestic unrest in the late 1960s and early 70s. ‘I was dead set against the Vietnam War,’ Trumbull told me in April 2014.

I did everything humanly possible to avoid getting involved in it. I was very fortunate to have been living in London. I had a permit to leave the country prior to working on 2001, but it was my presence in London and working on 2001 that allowed me to bypass the draft issue. And that was a very, very big issue that was on everybody’s minds – how to avoid the draft.

The Vietnam War had similarly been on the minds of the three rising film-makers with whom Trumbull would ultimately collaborate on the screenplay for Silent Running. (Although an article in the Hollywood Reporter2 credits the screenplay to Robert Dillon and Dennis Clark, neither of them appear to have played any significant role in the finished script, or film.) An extraordinary roll call of emerging talent, the Writers Guild credits for Trumbull’s first feature include ‘Mike Cimino’, who – as Michael Cimino – would go on to become the Academy Award-winning co-writer/director of The Deer Hunter (1978) (considered by some to be Hollywood’s definitive statement on the trauma of the war), and Steven Bochco, la...