![]()

1 A Funny Film

In Nick Hornby’s novel About a Boy (1998), 11-year-old Marcus resolves to lift the spirits of his mother, who has recently survived a suicide attempt. He orders dinner and tramps off to the video store, where he despairs that death is implicated in every title on every shelf. Finally he settles with relief on Groundhog Day (1993).

The back of the box was right: it was a funny film. This guy was stuck in the same day, over and over again, although they didn’t really explain how that happened, which Marcus thought was weak … But then the film changed, and became all about suicide. This guy was so fed up with being stuck in the same day over and over for hundreds of years that he tried to kill himself. It was no good, though. Whatever he did, he still woke up the next morning (except it wasn’t the next morning. It was this morning, the morning he always woke up on) …

Why wasn’t there any warning? There must be loads of people who wanted to watch a good comedy just after they’d tried to kill themselves. Supposing they all chose this one?1

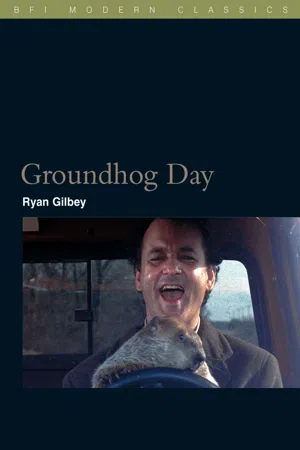

It is easy to sympathise withMarcus. Groundhog Day does, after all, promise to be a straight-shooting movie: no kinks, no curveballs. It takes an established clown (Bill Murray), albeit one with a uniquely unsavoury kind of charm, and an effervescent former model (Andie Mac Dowell), and lets them loose in a folksy American small town – that safest of cinematic playgrounds where the equipment is heavily supervised, and there are no sharp corners or abrasive surfaces. The picture is co-written and directed by Harold Ramis, known for his part in irreverent mainstream entertainment (co-writing Meatballs [1979] and Ghostbusters [1984], directing Caddyshack [1980] and National Lampoon’s Vacation [1983]). More reassurance. But as Marcus discovered, Groundhog Day is a devious beast.

At first glance it seems to be a typical narrative of redemption. Murray plays Phil Connors, a television weathercaster who finds himself repeating indefinitely one drab day in the milk-and-cookies town of Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania: no matter what improprieties he has perpetrated in the previous 24 hours, or how definitively he has annihilated himself, he is returned intact to his bed each morning at 5.59 a.m.

He has come to Punxsutawney with his producer, Rita Hanson (MacDowell), after whom he half-heartedly pants as though it were a contractual obligation, and a cameraman, Larry (Chris Elliott), whom he baldly despises. There, they are to cover the festivities of Groundhog Day on 2 February. The celebration hinges on a rodent named Phil, which is exhorted to predict the date on which winter will give way to spring; if he sees his shadow when released from his bunker, winter will extend for six more weeks. This has its roots in Christian tradition – 2 February being the date for Candlemas – but it brings just the right touch of exotic unfamiliarity to the film, and to its title. (You can’t help feeling that audiences lost out in France and Brazil, where it was renamed A Day without End and The Black Hole of Love respectively.)

Punxsutawney is for Phil a kind of expanded Room 101, no less claustrophobic and terrifying than Winston Smith’s ordeal by rats. Being trapped in a place where everyone is worthy of scorn recalls Sartre’s observation that ‘Hell is – other people!’2 Then again, it’s difficult to imagine a location that wouldn’t prompt Phil to lash out wherever he turned, other than a hall of mirrors.

It’s a Wonderful Life (Frank Capra / Liberty Films, 1947)

Even on a first viewing the movie feels warmly familiar. It deliberately evokes two cherished works that have permeated modern storytelling: Frank Capra’s 1947 cockle-warmer It’s a Wonderful Life and Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, a raucous modern version of which Murray had already appeared in five years earlier (Scrooged).

From Capra, the film takes the snowy small-town setting, the opportunity for one man to quantify his effect on other people, and the inbuilt ‘rewind’ and ‘re-edit’ functions that allow us to skip back and glimpse reality in a modified form. (In early drafts of Danny Rubin’s screenplay, Capra’s film was playing at Punxsutawney’s only cinema. ‘Not again!’ screams Phil. ‘I’ve seen it a jillion times.’3)

From Dickens, the picture borrows the idea of a decayed soul getting the chance to pick himself up, dust himself off and start all over again, though here it’s millions of chances, millions of starts. Groundhog Day manipulates the notion of structure: though it has three discernible acts, the entire picture is disguised as a succession of beginnings. (Even the end, after the spell has been broken, is another kind of beginning.) Every story is to some extent launched with ‘once upon a time’, but Groundhog Day takes this to its maddening extreme, offering an unspecified string of once-upon-a-times, in the manner of Italo Calvino’s novel If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller, which reverts to a new beginning with the dawn of each chapter. The film also riffs relentlessly upon the opening of the archetypal blues lament. Now the mournful line ‘I woke up this morning…’ becomes multiplied into any number of awakenings, any number of mornings, though always in the same sad bed.

Groundhog Day was released in Britain on 7 May 1993, shortly after its US opening (12 February), and met with unanimous praise. TheLondon Evening Standard called it ‘an exceptionally sparky film’.4 Time Out declared it ‘one of the funniest, most intellectually stimulating comedies to emerge from the Hollywood mainstream in years’5while the Independent on Sunday said, ‘This is a one-gag movie, but it’s a hell of a gag.’6At the BAFTA ceremony in 1994, it won the Best Screenplay award for Ramis and Rubin.

What criticisms Groundhog Day attracted were mostly aimed at its director, who is not a man renowned for overstating his own talents. (‘It’s not like I’m going to leap from Meatballs to 8½,’ he once said about his prospects.7) His direction was judged to be ‘nothing special’8 and ‘too cool and restrained’.9 On the contrary, restraint is precisely what is required here. The material is so outlandish that a corresponding zaniness behind the camera could only have nudged the picture into chaos. Like Preston Sturges before him and Spike Jonze after him, Ramis keeps a steady hand at all times, treating the material with the calm deference of a nightwatchman guarding a precious stone.

It was not always apparent that those closest to the film knew what they had on their hands – unless, that is, they knew only too well, and were minded to play up its more palatable elements. In the weeks before the US release, Ramis could be heard expounding his film’s virtues, coming on like Ron Howard. ‘It’s very funny, warm, romantic, spiritually uplifting and absolutely unique,’ he trumpeted.10Well, yes. There’s not an adjective there you could quibble with, though there are plenty that you might care to add. Ramis could also have said ‘experimental’, ‘challenging’ or ‘ambivalent’. But it would have been ridiculous to do so. Those words don’t sell tickets. And Groundhog Day sold a lot: the picture grossed $70.9 million at the US box-office alone.

Critics were quick to corroborate Ramis’s claims for his movie. Several phrases kept cropping up in reviews – ‘old-fashioned’, ‘feel-good’, ‘Capraesque’. Many writers did commend the film for resisting the descent into sentimentality commonly associated with these descriptions. Still, there remained little advance warning to tip off the Ordinary Joe in the street, or the Unsuspecting Marcus in the video store, about the depths of existential despair to which the film’s hero would sink before devoting himself to a life of productivity and altruism – a transformation that, as the Sunday Telegraph among others observed, is effected purely because ‘he has exhausted all the alternatives’.11

Strangely, the only hint that Groundhog Day might in some way prove to be untrustworthy could be found in one of the rare lukewarm notices with which it was greeted. Variety griped that it was hard to know ‘when [Murray is] still being ironically [sic] or actually attempting to be sincere… a little more genuine feeling along the way wouldn’t have hurt, and when [the film] finally does give in to its Capraesque side, it’s satisfying’.12

In complaining that the conventional flow of emotion was impeded, and in berating the film for not honouring the formula that it appeared to uphold, the Variety review inadvertently acknowledged one of the film’s most bewitching qualities. As the New Statesman noted, it ‘appeals at once to absolute idealism and absolute cynicism’.13 Depending on the eye of the beholder, this particular glass can appear half-full or half-empty – brimming over with the milk of human kindness, or shattered into pieces on the floor. It’s a kind of miracle that neither interpretation ever fully negates the other.

This above all else is what makes it rewarding to keep returning to Groundhog Day. It’s a gorgeous irony that this film, about a man doomed to live one day for eternity, is anything but predictable. The absence of explanation that irritated Marcus in About a Boy – ‘he liked to know how things worked,’ writes Hornby14 – has actually preserved the film’s enigma, and increased its allure.

Some drafts of the script, written by Rubin and subsequently rewritten by Ramis, had experimented with various reasons for Phil Connors’s predicament. It would be hard now to express an adequate degree of gratitude that these were jettisoned. In a medium anchored by exposition, motivation, back-story and closure, Groundhog Day is a film that dares to withhold. It might take its initial cue from A Christmas Carol, but Ebenezer Scrooge gets off lightly compared to Phil Connors. While ghosts accompany Scrooge, commenting helpfully on his torment, Phil is abandoned without instruction or insight in his icy, isolated hell. The audience, similarly stranded, will know how he feels.

The film functions as an open-ended compendium of speculative alternative days, where Phil’s actions impact upon the ensuing 24 hours in ways that are sometimes painstakingly itemised, sometimes merely alluded to, so that we can never be certain exactly how long he spends in limbo.

Other film-makers have tended when daydreaming about the nature of fate to restrict themselves to a finite schedule of parallel realities. There were two in the case of Smoking/No Smoking (1993), directed by Alain Resnais from the plays by Alan Ayckbourn, tracing the implications resulting from one woman’s decision to smoke a cigarette – or not. And there were three realities bouncing off a single springboard in Tom Tykwer’s Run Lola Run (1998), influenced by Krzysztof Kießlowski’s 1981 Blind Chance. Tykwer’s film trailed its high-speed heroine through three different versions of the same hectic twenty-minute period; Kießlowski’s more meditative template proposed a trio of contrasting outcomes in the life of one man scrambling to catch a train. The use of the rail journey as catalyst for alternative realities resurfaced in Sliding Doors (1997), where a Hollywood star (Gwyneth Paltrow) and a helping of romantic comedy banished any whiff of Polish austerity.

It is not just to the parallel-reality sub-genre that Groundhog Day belongs, but also to the more illustrious species of the psychological mystery movie, where the point is the resonance of the mystery, rather than its solution. In David Lynch’s twin noir nightmares, Lost Highway (1996) and Mulholland Dr. (2001), one reality is simply substituted for another halfway through the narrative, without explanation or warning. Kießlowski himself revisited the concept of multiple realities a decade after Blind Chance in The Double Life of Veronique (1993), a film that contrives the same delicious obfuscation of logic as Groundhog Day. A lingering riddle, seductively phrased, will never hurt a film’s chances of longevity. Why are the guests unable to leave the dinner party in The Exterminating Angel (1962)? Wh...