- 60 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Ghost and Mrs Muir

About this book

Joseph Mankiewicz's romance, 'The Ghost and Mrs Muir', stars Gene Tierney as a widow who refuses to be frightened away from her seaside home by the ghost of a sea-captain, played by Rex Harrison. This study features a brief production history and a detailed filmography.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Ghost and Mrs Muir by Frieda Grafe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medien & darstellende Kunst & Filmgeschichte & Filmkritik. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

HACKS AND WHORES: SCREENWRITING

The film was only a moderate success when it was released in America. Mankiewicz explained this by saying that his apprentice-piece, rather than having the stylistic coherence that might have been achieved by an auteur, possessed only the uniformity of a studio production moulded by Zanuck. Philip Dunne blames the screenplay: 'The basic trouble in the script is that once the ghost drops out of the story, it tends to sag, and we had to go through a series of big lapses to get him in again at the end. That was the weakness inherent in the book, and there was really no way to solve it.'

The novel itself doesn't have these problems, because the ghost, for good reasons which are different from the film version, only disappears from the story momentarily, never definitively, and the idea of collaborating on a book only appears in the second part of the novel, after Lucy's unhappy affair with the ladies' man Miles Fairley. The problems the screenplay encountered arose first from the adaptation of the novel for the cinema, which made a visual spectacle out of an internalised, aural story, secondly from the fact that a women's novel, a female fantasy of self-discovery with a good few drily comic overtones, had to be transformed into a passionate love story, in line with the 40s Hollywood idea of what constituted a successful women's film. Rather than being seen, twofold, as a squatter, the character of the woman becomes a male fiction, a mere reiteration of the old formula expressed by the irritable publisher Sproule: 'Twenty million discontented females in the British Isles, unhappily, are writing novels.'

'Second-hand seafaring'

Rex Harrison, at the time not quite forty and under contract to Fox, is the perfect match for the attractive young widow. He plays a retired captain who, in the book, is too old for the sea, 'short in sight and wind, slower in thought and movement'.

The author of the novel, Leslie, and her book meet the same fate as Mrs Muir when she tries to place the book with a publisher. Women write women's fiction, cookery books or, at best, fictional biographies of romantic poets.

Not that a more respectful treatment of the little novel would have yielded a better film. It was, indeed, the book's good fortune that no one involved really felt responsible as an author. This meant that the material could go on working autonomously, with resistances, gaps and inconsistencies. The rushes of the first few days' shooting suggest that Mankiewicz was closer to the author's intentions than Dunne. 'Haunted, how perfectly fascinating,' says Lucy with delight, completely reversing the standard scenarios involving haunted houses, where masochistic women are usually victims. Mrs Muir loves the house at first sight, 'as if the house itself would welcome me, asking me to rescue it from being so empty'.

But then Mankiewicz did after all behave like a director working to contract and Dunne as Zanuck's hack writer: 'To put it bluntly, a screenwriter is basically a hack. It cannot be otherwise, as long as motion pictures remain a collaborative art. A screenwriter at best is a stylistic chameleon, he writes in the style of the original source.'

The film is detached, like a pastiche, and Dunne's treatment comes as close to English women's literature as he was able to get. In the first third of the novel Lucy and the captain have an intimate conversation that shows them at their most harmonious. '"Oh, Lucia," the captain said softly, "you are so little and so lovely, how I should have liked to have taken you to Norway and shown you the fiords in the midnight sun, and to China – what you have missed, Lucia, by being born too late to travel the Seven Seas with me! And what I've missed too."' In the film, poetically embellished, these are the captain's words of farewell to the sleeping Lucy. He speaks them emphatically, as if reciting a poem, in order to legitimise the improbable invention of the entire film as a dream.

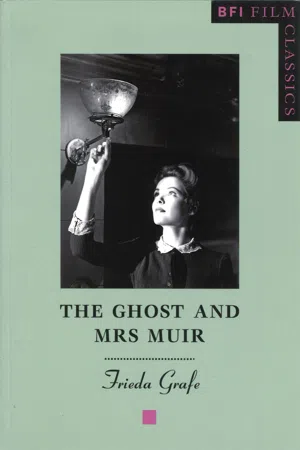

Overleaf: The repertoire of the ghost film genre – descending into the 'crypt'

Just as Dunne relies on English women's fiction, Mankiewicz draws on the repertoire of the ghost film genre for scenes like the one in which Lucy, on her first meeting with the ghost, descends, a candle in her hand, into the crypt – the kitchen. Disinterestedly as Mankiewicz directs this scene, it reveals that genre conventions are the fundamental abstract formulae of the cinema.

By his own account, Mankiewicz also learned his approach to the cinema and his trade from the hacks, in the days of silent film, around the time of the changeover to sound, when the writing of a film was divided between two people, one of them responsible for continuity, the other for dialogue – men who were incapable of writing a decent letter, but who were 'nevertheless real writers in their own medium'. Mankiewicz was convinced that a new kind of writing had emerged with and for the cinema, one which altered the artistic function of language and its relationship to the audience as practised by the novel and the theatre. It assimilated certain visual and staging devices, and addressed the audience directly as a spoken language in actual voices which called for a response. Which is why Mankiewicz, even in the films that he only produced, exerted more influence on dialogue than on plot.

When I was finishing my studies, a writer was somebody who conceived and created the whole of a novel, a poem or a play, but who couldn't call himself a writer until he had sold his work: the novel, the poem or the play didn't exist until they were published, or acted. With the arrival of the sound film a completely new job emerged. A writer was engaged to write, or to adapt the work of others, and he was paid by the week. And he could rely on his income, even if the completed work wasn't what the client wanted.

The forms of marketable writing in Hollywood were shaped not only by production methods, but at least as much by those who delivered them, by the imported East Coast writers who despised their work for film, who hid their shame behind cynicism, although what they had done before in newspaper offices in New York and Chicago had also been unoriginal hack work.

Mankiewicz, not so much out of conformism as out of an insight into the specific nature of his work, didn't see its reproductive nature as discreditable, but more as something required by the medium: 'I'm not good at "originals". I have to start off with something, some plot situation; then I rework it in my own language and my own form.'

Despite his being obliged to respect Dunne's screenplay, Mankiewicz's interventions, his reworkings and rewrites, quite apart from those specifically mentioned by Dunne, are often apparent at many points as a third or fourth reading of the subtext. It would never have occurred to the captain as conceived by Leslie to quote poetry, certainly not Keats' Ode to a Nightingale. This is one of a series of references to English romanticism with which the film tries to evoke the aura of the female imagination, maybe even the memory, in educated viewers, of lines like 'the viewless wings of Poesy .... I have been half in love with easeful Death ... Was it a vision or a waking dream?'

Mankiewicz certainly chose this poem because it contains the line which became the title of Fitzgerald's novel Tender is the Night. Mankiewicz had rewritten Fitzgerald's dialogue for Three Comrades to make it more filmic, and had provoked enraged protests from him. 'If I go down at all in literary history, in a footnote, it will be as the swine who rewrote F. Scott Fitzgerald.'

Adapting Miss Leslie's novel for the cinema involved more than the usual problems of visualisation; because Mrs Muir in the book doesn't see ghosts, she hears the captain's voice inside her. 'The voice was not really there, she did not hear it with her ears. It seemed to come straight into her mind like thought.'

The intentions of the adapters, who were aiming at a predominantly female audience, required a radical restructuring, whose details speak for themselves. The location is no longer a lonely, forbidding stone house, but a sunny Californian building made of lightweight materials. In the novel the captain doesn't demand that Lucy put his portrait in her bedroom; she does it of her own accord and thus in her imagination she breaks the great taboo. In the Hollywood love story, when the same thing happens at his command, it is the kind of suggestive circumvention of the censor of which Lubitsch was such a master.

Lucy, about to undress, covers the captain's portrait

In the book, in order to clarify to herself how she is to make sense of the captain's voice – and so that Leslie can do the same thing for her readers – Mrs Muir goes to an analyst, who proposes that she sublimate and rationalise the voice. But Mrs Muir has her own ideas about how she can put to rest the unruly ghost within herself. That will be the book.

In order to externalise this inward-looking female perspective, which is not hysterical, immediate identification, the classic Hollywood film needs a concert of differentiated voices. It needs a story with realised characters, because it cannot imagine any other way of attracting and holding an audience. This means that the film strays close to the boundaries of plausibility, and the audience's credulity nearly becomes active reflection about the medium and narration, in order for the film to work.

Fairley has stolen a handkerchief from Mrs Muir so that he can arrange to see her again.

FAIRLEY: Life is just one coincidence after another.

LUCY: Thank you for returning my handkerchief.

FAIRLEY: I feel ashamed of having taken it.

LUCY: You should be.

FAIRLEY: Only as a writer, of course. It is much too obvious a device.

LUCY: And in questionable taste.

The film allows ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- In the Name of the Author

- Director's Studio of a Creative Producer

- Hacks and Whores: Screenwriting

- The Haunted House Upside Down

- The Most Forward Gentleman

- Images Set to Music and to Words

- Man in the Picture is Woman in the Mirror

- The Ambition to be a Producer/Writer/Director

- Credits

- Bibliography

- eCopyright