![]()

1

Background

Advances in technology have arguably had a greater impact on the development of industries and businesses over the past 50 years than any other external force. Technology has the power to disrupt, challenge and transform existing industries alongside creating entirely new ones.

Technology advancements are frequent and numerous. There is a constant and relentless pace of innovation that can often leave you with the feeling that the potential shown by one advancement has not even been remotely realized before focus moves on to the next cutting-edge development. Within businesses, those in charge of strategy and in leadership positions such as CEOs, MDs, COOs and board members have varied and demanding jobs and, unsurprisingly, need to spend a great deal of time keeping up with developments in the markets in which they operate, rather than necessarily focusing exclusively on technology. Many conversations I have had with CEOs have been along the lines that they know technology is a huge value opportunity for their business but they simply don’t have the level of detailed understanding as to which technologies may be most relevant or the time to keep up with the constant innovation. Many of them are also scarred from previous investments in IT that perhaps haven’t delivered on the value they promised and as such are sceptical that future investment into technology will yield real value.

Therefore, this book is aimed at business leaders, business owners and senior managers who want to develop a meaningful understanding of technology and its real value potential within businesses, and in particular to understand how to apply developments in technology to familiar business principles such as revenues, profit, cash and valuation.

For many business leaders, consistently utilizing technology as a tool for creating meaningful value seems to be elusive and often difficult. There is a typical rhetoric that often describes two distinct and separate groups of people within a company as ‘The Business’ and ‘IT’. It is quite an odd way to divide up a business if you think about it, given how important IT can be to all areas of a business, and its separation in this context highlights the gulf in thinking and understanding that often exists between IT and other senior strategic leadership individuals. If Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus attempts to highlight (albeit in a light-hearted manner) the generalized difference in communication and thinking between men and women and the issues this can create, then surely there must be an equivalent to describe the gulf between IT and The Business.

How do you overcome this gulf? Some will throw around the cliché that ‘communication is key’ and the solution is simply for ‘IT’ to communicate more frequently. This may certainly help, but I think the real key to effective communication is an element of understanding on both sides of the conversation, i.e. both parties understand their own and the other party’s position and have the confidence therefore to challenge and question the other side from a position of understanding, not ignorance.

My hope is that through reading this book you will develop a robust framework for assessing technology opportunities within your businesses and the value they may create. I want you to be able to do this with confidence and in order to achieve this, we will construct our framework on robust and familiar foundations – business and financial, rather than technology principles. This is the key to having constructive and valuable conversations between business leaders and IT – if business leaders go into every technology-related conversation at a disadvantage because they feel they need to get into technical concepts, or they don’t feel confident in their own understanding of the language and terms the other person is using, it is unlikely to yield positive results.

I am confident that by the end you will have gained an increased level of confidence and interest for technology as a driver of value in the business and most importantly you will have a much clearer understanding of the different ways, depending on your business strategy, in which technology can create value within your business.

Of course in a book like this it’s impossible to cover everything, so I’ve deliberately chosen technologies that are common, applicable to most business environments, and that have the capability to add real demonstrable value to your business. This means there are technologies that I have left out, either because I think there are better opportunities for value creation out there or because there are no clear signs that they are adding value above and beyond a comparable technology. Blockchain is an example of this; it’s certainly had a lot of profile and its role in bringing certain cryptocurrencies to life is notable. However, at this point in time I remain unconvinced that Blockchain today, or even in the medium term, is going to be solving problems for businesses that they can’t already solve with conventional technologies if they put their minds to it. It’s often not the technology that is preventing some of these solutions from materializing, but other factors – politics, competing interests, processes, cost and many other things – that cause the problems. For that reason, I have focused on technologies that solve more pressing problems for most businesses and through which a more demonstrable return on investment will be forthcoming in the short and medium term.

It’s also important to note that whilst this book is not aimed at the technology community or technology professionals as its primary audience, it may offer readers in this field some new ideas as to how to frame and position technology with their ‘business’ colleagues using language more familiar to business leaders.

![]()

2

Valuation and Value Creation

Demonstrating the value that a course of action or decision will generate is one of the most basic and universally accepted techniques for successfully asking for something. In any normal business, a request to invest company resources, be those cash or people (or both), will be met with the question: ‘Why? What is the business case?’

This is then usually followed by the process of breaking the request down into the associated costs and benefits and then comparing these, taking risks into account, before arriving at a conclusion as to whether an investment makes sense. This is a hugely subjective process and itself often the cause of much of the discontent that surrounds technology investments (see Chapter 6 for an in-depth look at this process).

However, in order for us to talk more plainly throughout this book and ensure we continue to frame our technology assessment framework in terms of business ‘value’, we need a common and simple understanding of how businesses do create and measure value. For that reason, this book is going to base its concept of value creation around the typical approaches used to value businesses.

It’s worth clarifying that I am using a traditional form of value quantification here – namely financial value (and by implication, shareholder value). However, that isn’t to say you shouldn’t or can’t create other kinds of value in a business – either alongside shareholder value or instead of. For example, social value, customer value, environmental value and personal value are all examples of different types of value you can create and no one can argue that one is more appropriate than the other. However, this book is unapologetically focused on shareholder value simply because it is generally what business owners mean when they talk about creating value.

This chapter will look at three of the most common methods used for valuing businesses and break each of them down into their component parts. We will then examine those components to understand the different ways in which technology can impact them.

The three valuation models we are going to look at are the comparable transactions valuation, comparable company analysis and the discount of future cash flows approach.

Comparable Transactions

The simplest of valuation methodologies, this tries to put a value on a business using a measure of the business’s sustainable earnings and a multiplier based upon previous transactions (acquisitions) of businesses of a similar scale and in a similar sector to your business. Typically used more in private markets, i.e. private equity, it’s a relatively simple valuation methodology. The basic formula is to multiply a company’s earnings by a number (known as ‘the multiple of earnings’ or just ‘the multiple’) and then adjust for any debt or surplus cash that might exist in the business. The formula can be described as:

(Operational Earnings × Multiple) − Net Debt = Shareholder / Equity Value.1

More recently, the most frequently used measure of Operational Earnings is ‘EBITDA’, which is a crude measure of the underlying cash profitability of a company. It is calculated as revenue less cost of sales and overheads and it typically strips out the impact of certain non-cash accounting items (depreciation and amortization), and is stated before tax and interest in order to try and give a true picture of the company’s underlying cash profit. In some cases, EBITA is used instead (therefore leaving in the impact of depreciation to take account of continued capital expenditure), but generally in either approach amortization (the ‘A’) is ignored.

Net debt is effectively the difference between your debt items and your cash balance, and is largely impacted by how much of your profit you can convert into cash.

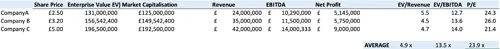

The multiple is a more subjective figure and slightly more difficult element to quantify. This is where the comparable data comes in. Take a look at the table below:

As you can see, there are three comparable transactions with the key metrics set out for EV/Sales (enterprise value/sales ratio), EV/EBITDA and EV/EBITA.

Now, a starting point for a valuation could be simply taking an average of those figures, but that only goes so far. If your company is truly ‘average’ then that may be a fair approach but inevitably the valuation needs to be adjusted to reflect the value in your particular business. What sort of factors then would cause the multiple applied to move up or down from the average?

The answer is lots of things! The most important factors in determining the multiple are the growth rate, coupled with the predictability of earnings (i.e. consistency). Ultimately, the multiple is a measure of risk and quality – the higher the perceived risk the lower the multiple. The higher the quality (and therefore lower perceived risk) the higher the multiple. As a result there are many other variables that can influence the multiple – factors such as sector, margins (are they high and predictable?), visibility of earnings/levels of recurring revenue, scale, owned IP, brand value, trajectory of earnings, quality of the management team etc. Therefore, whilst this is a more complicated and clearly subjective area of the valuation process, it also offers lots of opportunity to influence the ultimate valuation, and technology can play a valuable role in many of these areas. For example, businesses that are well run operationally with good systems supporting the day-to-day business could be seen as more scalable and with less operational risk, meaning a better multiple can be justified than a comparable business with a less well-developed infrastructure. The reverse is also true. I’ve seen transactions that start out with a certain valuation at the ‘heads of terms’ stage (early stage in the process where you agree key points of the deal before getting into diligence) only to have that valuation reduced once diligence has completed because a number of operational and technology issues are uncovered that require a downgrade to price.

Whilst this is a relatively simple valuation approach, there are of course drawbacks to this method:

1 This valuation methodology is most relevant when you are trying to sell or buy a business. It is not that relevant in making business decisions on a day-to-day basis. It gives a clear indication of what a willing buyer is prepared to pay to a willing seller. It doesn’t provide an objective measure of value creation;

2 It relies on you finding appropriately similar businesses to compare to;

3 Synergy opportunities may exist for some buyers that are not available to others and this can affect the valuation;

4 The level of competition in a sales process etc.

Key takeaways from the above:

1 The valuation depends largely on either revenue or profit (EBITDA or EBITA) and the multiple adjusted for net cash/debt;

2 All valuation is ultimately derived from cash generation. Revenue, profit, EBITDA, EBITA etc. are all proxies used to try and approximate cash generation;

3 The multiple is a measure of risk and quality and arguably the most subjective area of the methodology.

Comparable Company Analysis (cca) Approach

The comparable valuation methodology is similar in some respects to the comparable transactions approach except that, arguably, it provides you with a more accurate ongoing valuation since there is no ‘premium’ applied for the acquisition of the business – i.e. your basket of comparable companies doe...