- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Gold Rush

About this book

Matthew Solomon's study of Chaplin's The Gold Rush (1925) provides an in-depth discussion of the film's production and reception history, placing it in the context of the turn-of-the-century Alaska Klondike gold rush, and analyses the film's narrative and formal features, particularly its references to music-hall performance styles and tropes.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 A Film in Flux

There was not just one Gold Rush – there have been many. Charlie Chaplin, the film’s director and star, produced and released two different versions, a silent version in 1924–5 and a sound version in 1941–2. The sound version includes Chaplin’s voiceover narration and a musical score that Chaplin wrote, along with a few sound effects and new title credits. Besides excising all of the intertitles and adding a synchronised soundtrack, which necessitated projection at a consistent rate of twenty-four frames per second rather than the slower speeds typically used to shoot and project films during the silent period, Chaplin also made a number of changes to the visual track. Chaplin tinkered with many parts of the film in preparing the sound version, substituting alternative takes – or different parts of the same take – by drawing from thousands of outtakes that remained in his vaults. United Artists re-released the sound version to theatres again in 1956, but in the interim, Chaplin neglected to renew copyright on the silent version. Since copyright on the silent version expired in the United States twenty-eight years after its release, it was part of the American public domain from 1953 until 1997, at which time its copyright was retroactively restored.1 So, for most of the second half of the twentieth century, it was duplicated, distributed and re-duplicated on 8mm and 16mm film, videocassette and videodisc in dozens of different versions. As copies proliferated, so did its variations, many of which were derived from one or more of the versions already in circulation. None is exactly the same since changes were introduced with every new generation of copies and every transfer from one format to another. Some of the differences between versions are subtle – a slight shift in framing, the substitution of one take or camera angle for another, nearly identical shot – but others, like the addition or substitution of a soundtrack and/or a change of speed, are far more noticeable.2 Chaplin insisted that the seventy-two-minute sound version ‘with music and words’ was The Gold Rush (hence its primacy – and formerly its exclusivity – on all video releases authorised by Chaplin’s Roy Export Company). Audiences, however, have seen The Gold Rush in different versions in formats that have ranged from 35mm film to video files streaming online. Unlike fully 70 per cent of American silent feature films, which are now considered lost, The Gold Rush survives. Moreover, it is readily accessible – unlike most surviving silent feature films.3 Copies abound, but many differ. Thus, it is truly a film of ‘permutations’.4

‘This is the picture I want to be remembered by’, Chaplin said of The Gold Rush in 1925.5 But, how the film is remembered depends partly on which version(s) one has seen and heard. There were at least three different versions screened for paying audiences in 1925 alone, which makes the conventional notation ‘The Gold Rush (1925)’ somewhat unclear, especially since no complete print – much less a negative – of the film in any of the forms in which it was originally shown or distributed is known to survive. The sound version, The Gold Rush (1942), which has varied comparatively little since its theatrical release, is the ‘director’s cut’, and Chaplin would have preferred that it were the only cut. In a legal statement made some time after 1956, Chaplin stated that following the ‘1942 revival’ of The Gold Rush, he ‘gave instructions that the 1925 silent version should no longer be shown and ordered the destruction of the original negatives, fine grains and prints thereof’.6

Like many features of the silent period, The Gold Rush was shot primarily with two cameras placed side by side – what one observer on the set of the film described as ‘the two inseparable cameras’.7 Chaplin’s longtime cameraman Roland ‘Rollie’ Totheroh operated one of the cameras and Totheroh’s assistant Jack Wilson generally operated the other. In daily production reports, the infrequent occasions when only one camera was used were specially noted, as were the even more infrequent occasions when four or six cameras were used (for certain location shots and special effects).8 Filming every take with two parallel cameras facilitated the creation of two negatives, something Chaplin had done since his 1917 contract with First National stipulated it.9 This practice necessarily introduced slight variations in framing and speed between the negative shot with the A camera and the negative shot with the B camera. Each and every positive print struck from one of these negatives was also subject to further alterations by distributors, censors and exhibitors, as well as to later changes by collectors, archivists and re-distributors (some of whom combined footage from different prints), all while suffering the inevitable physical and chemical deterioration that occurs with projection and the passage of time.

Filming The Gold Rush with the customary two cameras in the Chaplin studios in 1925. (From left to right) Jack Wilson, Rollie Totheroh, Chaplin and Associate Director Chuck Riesner © Roy Export Company Establishment, scan courtesy of Cineteca di Bologna

From the moment Chaplin finished shooting The Gold Rush, it was a film in flux. According to daily production reports, the final shot of the film was taken on 21 May 1925. When Variety announced ‘Chaplin’s “Gold Rush” Completed’, Chaplin said he was still unsure whether it would eventually be ten, eleven or twelve reels long.10 Because Chaplin had edited parts of the film already (as was his practice), he was able to preview the film just one week after the last shot at the Forum Theatre in Los Angeles on 28 May 1925.11 Another month later, following four more weeks of ‘cutting and editing’ recorded in daily production reports, The Gold Rush officially premiered on 26 June 1925 at Sid Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood. At this point, the film was 9760 feet long (almost ten reels) and reportedly ran some 120 minutes.12 Lita Grey (née Lillita MacMurray), who was Chaplin’s co-star in the film before marrying him, recalled, ‘He spent a long time – over two months – editing the film and cut a whole reel from it after the premiere’.13 Indeed, by the time The Gold Rush had its New York premiere at the Mark Strand Theatre on 16 August 1925, it had been reduced to 8924 feet (nine reels) and ran 96 minutes.14 Some felt it should have been even shorter, with Herbert Howe of Photoplay writing that The Gold Rush needed ‘at least three dead reels extracted before they affect the good ones’.15 The version that was distributed in 1925 was abbreviated a bit further – though not by three reels – to the length of 8555 feet.16

Lita Grey signed a contract on 2 March 1924 to co-star with Chaplin in his new comedy, © Roy Export Company Establishment

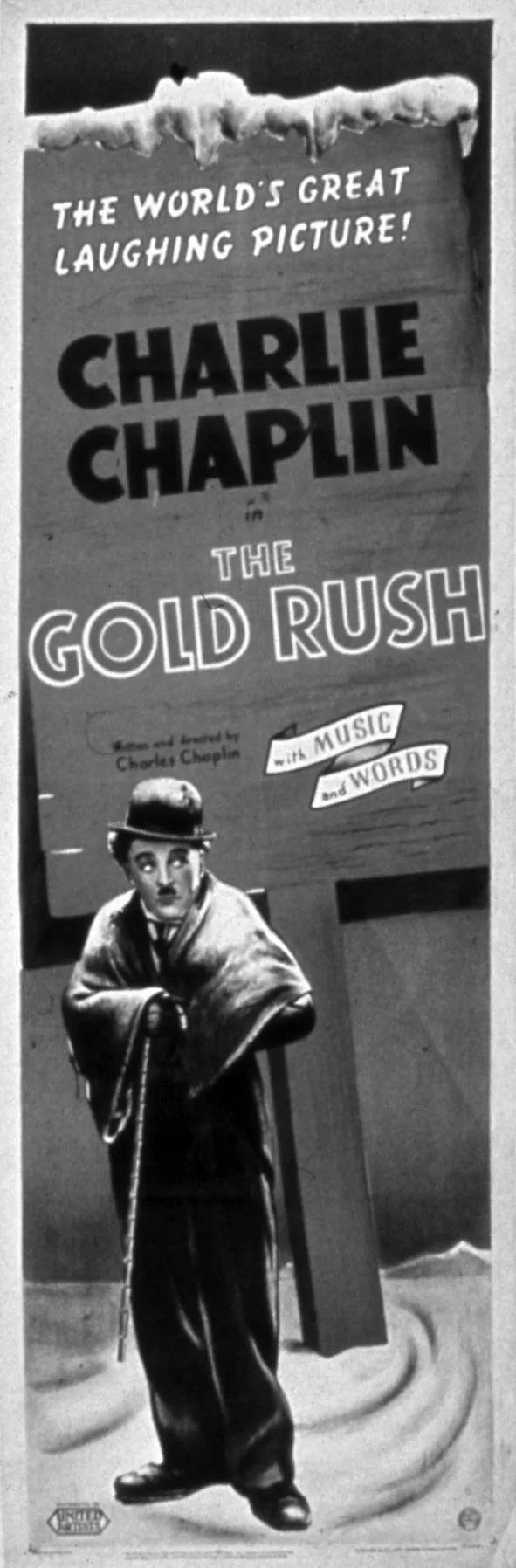

1942 poster

In 1941, Chaplin returned to The Gold Rush to revive it as a synchronised sound film and planned to cut even more. He told Variety he was going to cut it ‘down to 8,000 feet to increase its tempo’ and promised ‘“The Gold Rush” will be about 1,500 feet shorter than the original version’ – although it is not clear which version he considered to be ‘the original’.17 On 21 December 1941, Chaplin previewed the revival at the United Artists theatre in Inglewood, California. He made sound retakes over the next few weeks and screened a final cut of the sound version on 12 January 1942 for the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, immediately receiving MPPDA approval. The sound version premiered in New York at the Globe Theatre on 18 April 1942 and in Hollywood at the Paramount Theatre on 19 May 1942. As released, The Gold Rush (1942) is 6462 feet, with a screen time of seventy-two minutes.18 The length of the film allowed exhibitors to combine it with another feature to create wartime double bills: it was paired with Blondie for Victory (1942) in Oakland, California; with Torpedo Boat (1942) in Madison, Wisconsin and with Sergeant York (1941) in the state of New York.19

During the 1970s, when The Gold Rush was mainly available in silent 16mm film prints, Walter Kerr noted,

I once closely examined three different prints of The Gold Rush … to discover that in several sequences Chaplin had used alternate ‘takes.’ The chase through the Alaskan saloon, with Big Jim McKay trying to get his great paws on Charlie, exists in variant patterns.20

Close examination of versions that have circulated since that time reveals many such variant patterns, most of which were not a direct result of Chaplin’s creative decisions, but instead are due to the interventions of others. In a careful comparison of versions of The Gold Rush on videocassette, Alice...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- 1 A Film in Flux

- 2 An Unstable Text

- 3 The Total Film-Maker

- 4 Origins and Originality

- 5 The Work of the Artist and His Lawyers in an Age of Technological Reproducibility

- 6 ‘The Lucky Strike’

- 7 A Northern Comedy

- 8 Historical Referents

- 9 Making by Halves; Two Premieres

- 10 Revising and Reviving

- 11 Second-Best Ever

- 12 Un/Authorised Versions

- 13 Memorable Sequences

- 14 Outtakes, Parallel Takes and a Triple Take

- Notes

- Credits

- Select Bibliography

- eCopyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Gold Rush by Matthew Solomon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.