![]()

1 A Film Classic

As a child, I kept a running list of favourite films that I updated every year, or whenever I saw a new movie that usurped a beloved predecessor. When Mary Poppins (1964) came out I went crazy, and my mother contacted Disney Studios. In the mail came a majestic signed black-and-white photo of Julie Andrews, looking wistfully to the edge of the frame. Next year, my dedication skyrocketed when The Sound of Music was released. After writing streams of fan letters to Ms Andrews, it dawned on me that the star might not be reading them. Cleverly, I began my next one, ‘Dear Julie Andrews. If you are not Julie Andrews, if you are her secretary, please give this to her.’ No reply. Reading everything I could on her, I recall how she made her interviewer chuckle with the ‘Mary Poppins is a junky’ bumper sticker on her car. But I never caught the joke of her return address on the one item I’d received: Julie Andrews, Box 666, Beverly Hills, California.

Christopher Plummer also got my ardent attention. When his Captain von Trapp first sang, I cried, along with legions of others. Indeed, in the massive sea of Plummer, Andrews and The Sound of Music fans, I was but one small girl and, then as now, my enthusiasm often pales in comparison to that of others. I’d seen The Sound of Music three times (I’d only gone to Mary Poppins twice, hence proof), but plenty of people watched it more – a relatively new phenomenon at the time – particularly children and adult women, the film’s biggest fan base. One Australian woman, reported Fox, went so frequently that her local theatre decided to let her in for free.

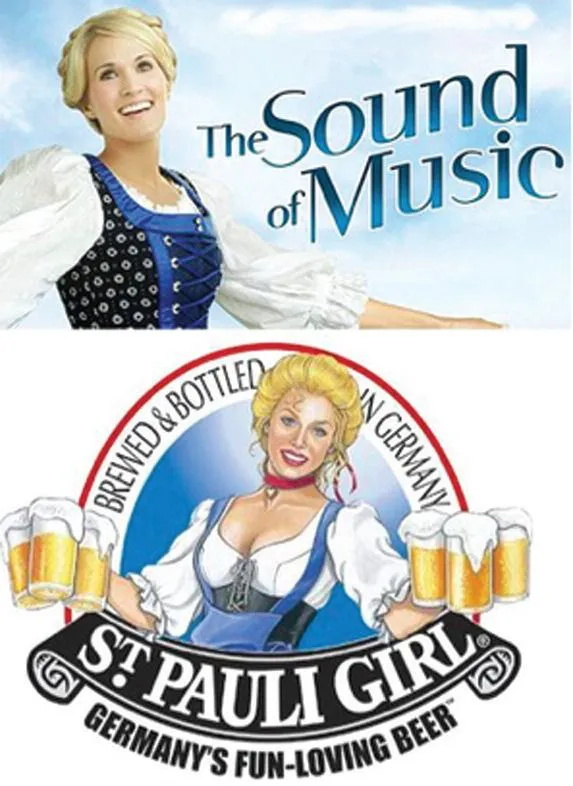

The Sound of Music has a long pedigree: the Trapp story – first recounted by Maria in 1949 – had been made into two German films before Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musical opened on Broadway in 1959. Since then, it’s enjoyed a revival there, in London and on stages all over the world, including Israel, Russia and Greece – and in countless regional theatres and school productions. In 2013, it was aired on US television in a live broadcast starring country singer and American Idol (2002–) winner Carrie Underwood. Trapp publications both real and fictional are available as memoirs, songbooks and even photo albums. Since 1965, Andrews and the seven young ‘von Trapps’ have turned up repeatedly in interviews and reunions, in DVD commentary, even in state-sponsored events, such as the occasion when the Austrian government decorated the two Trapp families for boosting postwar tourism in Austria. So intermingled have film and reality become that in the 1980s, US President Ronald Reagan played ‘Edelweiss’ for a visiting Austrian diplomat, believing it was his guest’s national anthem.1

Its aura remains undiminished. The Sound of Music lives on in early twenty-first-century forms like music videos (such as Gwen Stefani’s 2006 ‘Wind It Up’), online, in miniature and manipulated films (historical and imagined auditions, parodies, mash-ups, alternative universe versions, etc.), or in images for a pulpy vampire novel in which Maria, a hyper-carnal vampire, is a poor fit among Mother Zombie’s Abbey. Since 1999, when it premiered at London’s Lesbian and Gay Film Festival, Singalong Sound of Music has appeared in theatres, encouraging audience participation far beyond ‘singing along’. (To illustrate how the film’s economic aura remains just as undiminished, simply ask any theatre owner who has to rent the Singalong print.) Attendees of all ages come in character costume; in addition to dirndl- and lederhosen-clad kids, cross-dressed nuns are common. MCs instruct audiences to hiss at the Baroness and to release their small poppers during Maria and the Captain’s first kiss – the inevitable mistimed detonations are best.

A fan’s commentary on the 2013 live TV broadcast of The Sound of Music; Maria as vampire

There is a lot of financial firepower behind The Sound of Music’s position as a film classic. With an original theatrical run of three and a half years, and its figures adjusted for inflation, The Sound of Music is still, as of this writing (2015), one of the three top grossing US films – along with Star Wars (1977) and Gone with the Wind (1939) – with domestic box office at $159 million, excluding sales, rentals, rights and television deals.2 Just four years after its initial theatrical release, Fox re-released it, and in 1976, when ABC purchased the television rights, they paid an astonishing $15 million for a single showing. For the next twenty years, NBC broadcast The Sound of Music twenty-two times, and the film quickly morphed into ritual holiday viewing. The trend wasn’t unique to the US, in fact: The Sound of Music’s premiere on British TV, just like its premieres in French and German theatres, fell on Christmas Day, becoming a sort of religious relic of its own. In 2000, it was released on DVD and in 2010, in a Blu-ray edition with forty-fifth anniversary extras.

Though a booming business in the 1950s, LP soundtrack sales had fallen off by the next decade as youth-oriented music such as R&B, soul, rock, folk music and protest music became more popular. But none of these new trends affected The Sound of Music. Though it was priced higher than other LPs of the period, sales boomed, and the original soundtrack was released in foreign-language versions across the world. (Fox had taken the unprecedented step of re-recording the songs into different languages when the film was first released abroad.)

The LP’s artwork has become a classic, incorporating the same image that was used to publicise the film around the world. The image – not photographic but artistically rendered – melded the iconic picture of Maria on a green hilltop, simultaneously evoking her performances of ‘The Sound of Music’ and ‘Do Re Mi’. Just as she had been when singing ‘Music’, the joyous Andrews/Maria is prominently and centrally positioned. And, just as in ‘Do Re Mi’, she is leading her seven young charges, happy in their play clothes, to the top of ‘her’ mountain. The image seems to lob Renaissance perspective into the dustbin, opting for a near-medieval aesthetics and sense of scale that position Andrews as large and as centrally as it would Christ. The perspective reshapes the children into small, shrunken acolytes and places her poor co-star, the unhappy Plummer, off to the side, where he registers nothing but disapproval.

Camp and mass appeal

Across their wide demographics, The Sound of Music audiences are known for their repeated, ritualistic viewings and for their impassioned participation with the film. All the same, it contrasts sharply to other movies with similar viewers and viewing histories, such as The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), whose over-the-top theatrical indulgences and cynical edges are celebrated by camp enthusiasts everywhere. The Sound of Music, of course, has none of those features. Nor does it ask for the detachment camp typically requires, generating its passions through the familiar closeness people have with the film. Coupled with the sincerity of Julie Andrews’s vocal and performance style, and Wise and Lehman’s respectful treatment of the material, The Sound of Music is rather resistant to camp’s more detached, sardonic forms – although our Baroness does begin to flirt with it. The movie is intensely sincere. The acerbic Richard Rodgers knew that full well, writing to Harold Prince and Stephen Sondheim on the premiere of their own musical Company, ‘I think COMPANY is to cynicism what THE SOUND OF MUSIC is to sentimentality.’3

The only way The Sound of Music fails to line up as a film classic is when viewed through the inscrutable lens of High Art: that it is not, and of course was never meant to be. Coupled with its supreme sweetness, the film’s inability to pass as high culture has kept academic study of it somewhat at bay. For example, this volume of the BFI Film Classics appears more than twenty years into the series, despite the inaugural monograph on The Wizard of Oz (1939), by Salman Rushdie, whose own luminary stature may have prompted the choice. To be sure, people who dislike The Sound of Music are as numerous as those who love it; many straight men hate it, intellectuals and guardians of cultural taste hate it, east coast critics ripped it to shreds, and others refuse any contact with it, as if it were a bodily contaminant. Christopher Plummer, in fact, spent much of his long career referring to it as ‘The Sound of Mucus’ and trying to keep his distance. It wasn’t until 2010, in a special edition of The Oprah Winfrey Show (1986–2011), that Plummer participated in a full cast reunion.

Songs and ‘emotional remembrance’

For the fans who enjoy The Sound of Music, the trump card is nearly always its songs, whose staying power rivals if not surpasses that of the film itself. From Andrews’s unforgettable entrance in the film’s opening number, its music reaches out and fixes itself inside of you, whether you know it or not. As Richard Rodgers, whose melodies anchor the film, wrote: ‘Once heard, the words, when they are good words, may be superficially forgotten but they are emotionally remembered. The old … competitive cry of the composer, “Nobody whistles the words,” is simply not true.’4 When asked how they decided what parts of a show to put to music and what to leave as dialogue, the pair revealed that they ‘used music only when it became impossible to convey an emotional feeling by words alone’.5

For audiences, that music of ‘emotional remembrance’ secures The Sound of Music’s status as a classic. Its songs serve the same emotional function in the storyline – comforting scared children, celebrating Liesl’s giddy affections, urging Maria to pursue love beyond the Abbey. Of course, the emotional memories evoked by The Sound of Music were never the same for the different audiences who have watched it, but it’s clear that the film’s target was to generate a sense of sincere (‘authentic’) spirit and joy and a G-rated celebration of family and homeland, impressions sustained by Wise’s clear-headed direction, European locations that are both credible and lush, as well as Andrews’s vocal and acting style.

At the end of the opening credits, the words ‘Salzburg, Austria, in the last Golden Days of the Thirties’ appear on screen. Despite the precision of the line, the golden letters conscript audiences into a vague but rich emotional sense of time and place, rather than a regionally or historically specific one. Again, this is no small feat for a tale on the cusp of the Anschluss. By film’s end, as the Trapps trek into Switzerland – a geographical impossibility – the chorus encourages our joy in knowing that they are following their dream. Not to worry that they’re going the wrong way and that they aren’t carrying any supplies.

An emotional classic

With this in mind, The Sound of Music needs to be considered a ‘classic’ in a way that hasn’t been discussed before: as an emotional classic. This 1965 blockbuster tapped a nerve in audiences, whether or not they enjoyed it. Even non-fans were irritated precisely because of its unabashed trade in emotion. Pauline Kael infamously called it ‘a tribute to freshness that is so mechanically engineered, so shrewdly calculated that the background music rises, the already soft focus blurs and melts, and, upon that instant, you can hear all those noses blowing in the theatre.’6 As Kael makes clear, The Sound of Music has no lofty, heady aims, presuming more simply that feelings – abstracted and universalised, to be sure – seal the contract between film and audience. On that score, The Sound of Music aced it. In an interview late in life, director Robert Wise stressed how important it was for film-makers to engross their audiences so that ‘they can neve...