![]()

1 An Unlikely Story

Every day, to earn my daily bread

I go to the market where lies are bought,

Hopefully

I take up my place among the sellers.

Bertolt Brecht, ‘Hollywood’ (1942)

How could a film that was shot on a girdle-tight schedule, with no big-name talent, no real sets to speak of – just a couple of dingy motel rooms, a roadside diner, a low-rent nightclub and a Lincoln convertible flooded with an abundance of rear projection – and a legendary ‘lemonade-stand budget’ ultimately attain such classic status as Edgar G. Ulmer’s Detour?1 Sure, for standard second-billing fare, the film earned some hearty praise in the industry trade papers and the popular press when it was first released the week after Thanksgiving 1945. Even so, at the time of its debut, it would have been all but unthinkable that this unvarnished, gritty little B-picture would ever make it into the celebrated pantheon of film noir, let alone into the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress. Indeed, it wasn’t for many years, decades really, that the film found its most ardent following and finally outran its fate as the bastard child of one of Hollywood’s lowliest Poverty Row studios.

Humble origins

Detour began its long, twisted career as a slim 1939 pulp novel by Martin Goldsmith, an aspiring New York writer still in his mid-twenties at the time of publication, who had made Hollywood his base of operation by the late 30s. Goldsmith’s only other credits were another pulp, his first, Double Jeopardy, which he published the previous year, and a smattering of short stories sold to such magazines as Script and Cosmopolitan. Begging comparison to James M. Cain, and crafted in the style of the grand masters (Chandler, Hammett and others), Goldsmith’s Detour was hailed by The New York Times, in the hard-boiled parlance of the day, as ‘a red-hot, fast-stepping little number’. While he was still in his teens, on the eve of the Great Depression, Goldsmith had set out, much like the protagonist of his novel, to journey cross-country from New York ‘via the thumb-route’. Several years later, he reportedly financed the writing of Detour by loading people into the back of his Buick station wagon and driving them, at ‘$25 a head’, from New York to Los Angeles.2 In October 1944, after a long dry spell with no sign of the film rights to his book ever being purchased, Goldsmith pawned them off on producer Leon Fromkess, President and Head of Production at Producers Releasing Corporation (PRC).

One of the early cut-rate studios on Hollywood’s Poverty Row, PRC was famous for churning out cheap wartime entertainment, its three-letter company abbreviation sometimes mockingly referred to as ‘Pretty Rotten Crap’.3 Together with Monogram and Republic, PRC was one of the most storied studios in the ‘B-Hive’. It existed for a mere three years, from 1943 to 1946, before becoming Eagle-Lion Studios and eventually getting folded into United Artists in the early 50s. B-movies, which thrived in America throughout the 40s, were initially conceived as the bottom half of a double bill, in many cases as mere filler for a three-hour film programme that included newsreels and trailers for the price of a single admission. More generically, they were modest boilerplate features made on a severely limited budget, the kind of movies ‘in which the sets shake when an actor slams the door’.4 The agreement between Goldsmith and PRC was announced by Edwin Schallert in the Los Angeles Times, in an industry round-up of recent transactions, noting a supposed affinity between Goldsmith’s ‘murder mystery affair’ and Cain’s Double Indemnity and including a few gossipy details on the exchange: ‘Price is reported as $15,000, which is good for an independent.’5

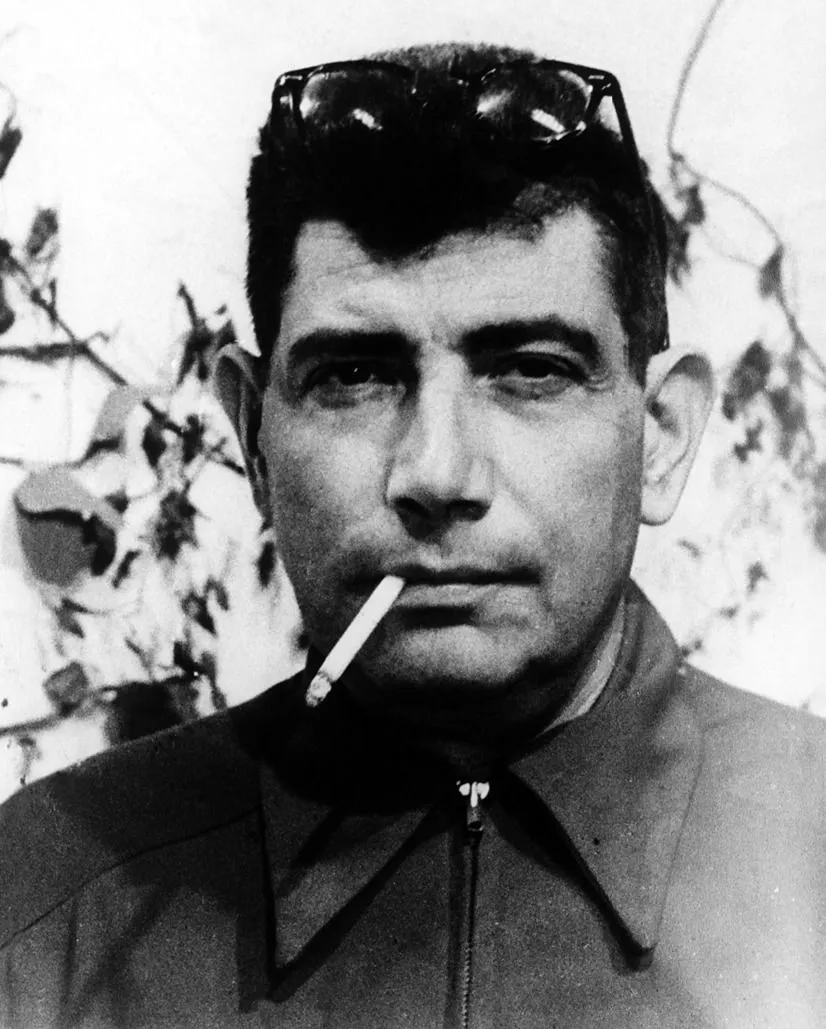

Studio portrait of Tom Neal

The lead actors selected for the film were all relatively unknown players from the American B-movie circuit. Ulmer had already worked together with Tom Neal, ‘a poor man’s Clark Gable’, on Club Havana (1945), one of his fly-by-night melodramas for PRC. With the handsome looks of an ex-boxer and a preternatural capacity for sulking, Neal was cast in the role of sad sack Al Roberts, a talented New York pianist who, in his desperate attempt to reach his fiancée in Los Angeles, gets dealt a bad hand a couple of times over. The fiancée, Sue Harvey, a nightclub singer and aspiring starlet turned hash-slinger, is played by Claudia Drake, a platinum-blonde with few spoken lines and precious little time on camera. In the more critical role of Vera, Al’s acid-tongued nemesis, a thoroughly down-and-out dame who fiendishly drops into the picture midway and keeps things in a headlock until her unceremonious exit, a feisty actress with a curiously apt nom de guerre, Ann Savage (née Bernice Maxine Lyon), was cast. Savage and Neal had previously played opposite each other in a few Bs for Columbia – William Castle’s Klondike Kate (1943), Lew Landers’s Two-Man Submarine (1944) and Herman Rotsten’s The Unwritten Code (1944) – and the two had an established screen chemistry and a bit of history, both on and off screen. (While shooting their first film together in 1943, Neal purportedly wasted no time overstepping the boundaries of professionalism, making an untoward pass at Savage by burying his tongue deep in her ear; she is said to have rewarded him with a prompt grazing of her knuckles across his face.6) Savage was brought in to see Ulmer on the set of Club Havana, with just over a week left before the shooting of Detour began; after a quick once-over, she immediately fell into favour with the director. Finally, Edmund MacDonald, who plays the amiable, pill-popping Florida bookie Charles Haskell, Jr, a man who gives Al a lift and – after revealing a few of his deepest, darkest secrets – ends up leaving him with more than just a free meal at a truck stop, was a character actor who had been around the block a few times, earning minor roles at PRC (one with Claudia Drake), Columbia, Paramount and elsewhere.

Studio portrait of Ann Savage

After Goldsmith and Fromkess settled the deal, a rumour circulated that actor John Garfield, who would soon go on to play an updated Al Roberts character in Tay Garnett’s The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), had read the novel and was eager to have Warner Bros. acquire the rights for him (Ann Sheridan was thought of for the role of Sue and Ida Lupino for Vera). The A-league studio reportedly made an offer to Fromkess of $25,000, but Fromkess, sensing he had his hands on a good pick, was unwilling to part with the material; subsequent talk of having Garfield come to PRC on loan-out from Warners never amounted to anything.7 In a serious break with Hollywood convention, Fromkess hired Goldsmith to write the screenplay from his own novel.8 What he produced was an elaborate, meandering text that would have required shooting a film with a run time of some two and half hours: indeed, more than twice the length of the sixty-eight minutes to which the film would finally be restricted. With seasoned input from associate producer/writer Martin Mooney, who had many PRC productions under his belt, and from Ulmer himself – who would later take much of the credit and rather emphatically dismiss Goldsmith’s novel as ‘a very bad book’ – the script was pared down to a manageable length. Entire sections had to be tossed out, others radically revised, and yet the threadbare quality it finally acquired, despite its intermittent reliance on the total suspension of disbelief, made for a good match with Ulmer’s minimalist, rough-hewn aesthetic.

In a considerable departure from Goldsmith’s novel, the tale is told exclusively from Al Roberts’s perspective. Roberts serves as the film’s narrator – delivering half his lines in a pained, edgy voice-over – whose primary task, beyond recounting his life as a cursed nightclub pianist and a cursed hitchhiker, is explaining the inexplicable, proving to himself, as well as to the audience, that he is essentially powerless in his losing battle against fate. The story of Al Roberts begins where it ends: on the open highway. Seated at the counter of a Nevada diner, in a tableau that evokes the canvas of Edward Hopper’s iconic 1942 painting Nighthawks, Roberts cries into his coffee mug. The tale he tells, whittled down from Goldsmith’s oversized script, is one of loss, with a tragic core that intensifies as the human wreckage piles up all around him until he is no longer able to find a way out. Al and Sue were once happily in love; they were, in Al’s words, ‘an ordinary healthy romance’, and he was a ‘pretty lucky guy’ (the film’s theme song ‘I Can’t Believe that You’re in Love with Me’, which plays a vital role in triggering Al’s flashbacks, was their song). But all this changes when Sue decides to try her luck in Hollywood – a fateful decision tantamount to jilting Al at the altar – sending things into a tailspin. Sue’s sudden absence cripples Al, shatters his dreams, and breeds resentment and bitterness. Yet when the opportunity arises to reunite with Sue in Los Angeles, he leaps at it, heading off on a cross-country journey with the initial giddiness of a young boy on Christmas morning. The journey, a white-knuckle ride down a mercilessly bleak desert highway, quickly turns sour. Al becomes entangled in an impermeable web of lies and deception, starting with the panicked swapping of his identity for Haskell’s, after Haskell’s mysterious death leaves him in a fix, and ending with Vera’s schemes of blackmail and extortion. By the film’s denouement, Al finds himself completely unhinged, with blood on his hands.

Ulmer’s breakthrough

Edgar Ulmer came to Detour at the apex of his four-year, eleven-film stint at PRC. An uncompromising Viennese aesthete, he had begun his training in Europe with Max Reinhardt, first venturing to the United States from Vienna in 1924, when Reinhardt’s play The Miracle was enjoying a successful run at New York’s Century Theatre. He went on to Hollywood to work in Universal’s art department and to assist F. W. Murnau, earning a credit as assistant art director on Murnau’s first American film, Sunrise (1927). He then returned to Europe to work on a couple of obscure, independent pictures – as production assistant on Louis Ralph’s adventure film Flucht in die Fremdenlegion (Escape to the Foreign Legion, 1929) and as a set builder on Robert Land’s Spiel um den Mann (Play around a Man, 1929) – and to pick up a credit as co-director of the acclaimed late Weimar silent Menschen am Sonntag (People on Sunday, 1930), filmed in Berlin in 1929 and created by a distinguished crew of budding Hollywood transplants (Robert and Curt Siodmak, Billy Wilder, Fred Zinnemann and Eugen Schüfftan).

Self-portrait of Edgar G. Ulmer

Ulmer ended up at PRC many years after what had turned out to be a miserable false start as a Hollywood studio director at Universal, where in 1934 he made his debut with the visually ambitious but professionally damaging horror film The Black Cat. (After defying studio boss Carl Laemmle in more ways than one – sneaking in a highbrow classical score to enhance the extravagant visual flourishes of the film, and stealing away the wife of Laemmle’s dear nephew Max Alexander while working on the set – he was branded persona non grata at Universal and beyond.) During the 30s, he bounced around, directing a string of pictures outside the studio system and far from Hollywood in nearly every respect: a low-budget Western, Thunder over Texas (1934), released under a pseudonym; a Canadian quota quickie From Nine to Nine (1936); a number of health shorts aimed at ethnic audiences; and finally, working in and around New York City throughout the late 30s, he directed a pair of Ukrainian operettas, four well-received Yiddish features and the all-black musical drama Moon over Harlem (1939). At PRC, he took on a mix of simple, wartime potboilers (which included such titles, all from 1943, as My Son the Hero, Girls in Chains and Jive Junction) and a few films that pushed the generic boundaries and brought him back to his European roots (Bluebeard, his Faust-inspired horror film indebted to a Weimar-era aesthetic, released in 1944, and one of his final films for PRC, Her Sister’s Secret, a 1946 weepie à la Douglas Sirk, among others). Detour, however, distinguished itself from the rest, not only in its comparatively generous reception and its unanticipated staying power, but also in its personal connection to the director and his identification with the project.

La politique des auteurs

Following a path similarly circuitous to the career of its director, Detour was first rediscovered in the mid-50s, hard on the heels of several unexpected paeans to Ulmer by French critics in the...