eBook - ePub

Cat People

About this book

Novelist and critic Kim Newman assesses the horror noir Cat People (1943), produced by Val Lewton and directed by Jacques Tourneur. This important and influential film is considered in the light of its place in film history and as a work of ambitious horror. The new edition includes a postscript about the sequel, The Curse of the Cat People.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

‘Cat People’

Everyone agrees that the title came first: Cat People.

In March 1942, Russian-born Val Lewton – formerly a pulp novelist, pornographer, publicist, story editor and second-unit producer – left a job with independent David O. Selznick and joined RKO Pictures as a producer. RKO had taken something of a pasting in Hollywood for their sponsorship of Orson Welles, which had led to the astonishing but financially unrewarding Citizen Kane (1941), the compromised release version of The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), an almighty feud with William Randolph Hearst, a great deal of footage shot in Brazil for a project that never coalesced, a reputation for overreaching and the downfall of a studio regime. Replacing vice-president in charge of production George Schaefer, who had brought Welles aboard, was Charles Koerner, who came over from the exhibition side of the business and was charged with executing the studio’s new-minted policy of ‘showmanship, not genius’.

Koerner recognised that Lewton had served an apprenticeship with Selznick (who could have given Welles lessons in megalomania, but was forgiven everything for delivering Gone with the Wind rather than Citizen Kane) and was ready to head up a production unit. It is often blithely stated that Koerner hired Lewton to produce B horror pictures,1 but Cat People and its successors2 were never strictly B product. RKO had B units churning out Falcon murder mysteries and Tim Holt Westerns, but Lewton’s horror films were always intended to be modestly budgeted A features and to go out at the top of double bills. If Cat People is to be assessed on a level playing field, it should be compared with Universal’s The Wolf Man (1941) or Paramount’s The Uninvited (1944) not PRC’s The Mad Monster (1942) or Monogram’s The Ape Man (1943).

Though RKO, briefly headed by David Selznick, had put out King Kong (1932) and that film’s fascinating by-blow The Most Dangerous Game (1932), the studio had not made much of an effort to get into the horror boom inaugurated by the similarly underdog Universal Pictures with Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931) and James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931). Instead, the studio – which could more accurately be labelled a distribution outfit since much of its product came from semi-independent producers like Walt Disney – made a name with the Astaire–Rogers musicals. Even Kong can’t quite comfortably be subsumed into the horror genre, since it makes its own rules. However, it was new broom Koerner’s policy that RKO should compete with Universal, which had renewed its lock on the monster franchise with George Waggner’s The Wolf Man, a commercial hit that had added a new monster to their pantheon and a new star (Lon Chaney Jr) to the genre. Lewton’s remit was to make horror films.

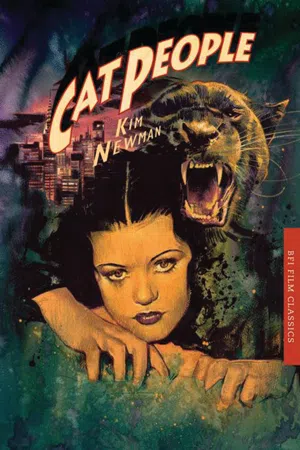

The poster

At RKO, Lewton began assembling a team, depending heavily on his contacts from the Selznick organisation: director Jacques Tourneur, with whom he had worked on the second unit of A Tale of Two Cities (1935), and writer DeWitt Bodeen, who had been a research assistant to Aldous Huxley on a Jane Eyre script that eventually became the 1944 film with Joan Fontaine and Orson Welles. They tell slightly different stories of how Cat People came to be. According to Tourneur,

Val Lewton called me up at RKO one day and said ‘Jacques, I’m going to produce a new picture here, and I’d like you to direct it.’ He said, ‘The head of the studio, Charles Koerner, was at a party last night and somebody suggested to him, “Why don’t you make a picture called Cat People?”’ And Charlie Koerner said to Lewton, ‘I thought about it all night and it kind of bothered me.’ So he called in Lewton and asked him to make the picture.3

Tourneur later added, ‘Val said: “I don’t know what to do.” It was a stupid title and Val, with his good taste, said that the only way to do it was not to make the blood-and-thunder cheap horror movie that the studio expected but something intelligent and in good taste.’4

Bodeen’s version is that

Val departed for RKO two weeks before I’d finished my work at Selznick’s, and when I phoned him, as I had promised, he quickly made arrangements for me to be hired at RKO as a contract writer at the Guild minimum, which was then $75 a week. When I reported for work, he ran off for me some US and British horror and suspense movies which were typical of what he did not want to do. We spent several days talking about subjects for the first script. Mr Koerner, who had personally welcomed me on my first day at the studio, was of the opinion that vampires, werewolves and man-made monsters had been overexploited and that ‘nobody has done much with cats’. He added that he had successfully audience-tested a title he considered highly exploitable – Cat People. ‘Let’s see what you can do with that,’ he ordered. When we were back in his office, Val looked at me glumly and said: ‘There’s no helping it – we’re stuck with that title. If you want to get out now, I won’t hold it against you.’

I had no intention of withdrawing, and he and I promptly started upon a careful examination of the cat in literature. There was more to be examined than we had expected. Val was one of the best-read men I’ve ever known, and the kind of avid reader who retains what he reads. After we had both read everything we could find pertaining to the cat in literature, Val had virtually decided to make his first movie from a short story, Algernon Blackwood’s ‘Ancient Sorceries’, which admirably lends itself to cinematic interpretation and could easily be re-titled Cat People. Negotiations had begun for the purchase of the screen rights when Val suddenly changed his mind. He arrived at his office unusually early and called me in at once. He had spent a sleepless night, he confessed, and had decided that instead of a picture with a foreign setting, he would do an original story laid in contemporary New York. It was to deal with a triangle – a normal young man falls in love with a strange foreign girl who is obsessed by abnormal fears, and when her obsession destroys his love and he turns for consolation to a very normal girl, his office co-worker, the discarded one, beset by jealousy, attempts to destroy the young man’s new love.5

Tourneur’s version of the metamorphosis from ‘Ancient Sorceries’6 to Cat People is that

At first, Bodeen wrote Cat People as a period thing but I argued against that. I said that if you’re going to have horror, the audience must be able to identify with the characters in order to be frightened. Now you can identify with an average guy like me, but how can we identify with a Lower Slobovian or a fellow with a big cape? You laugh at that. So we changed to modern period which I think is a good thing.7

Blackwood’s story (1906) has a contemporary setting, but concerns a medieval French town (in architecture not period) inhabited by a sect of devil-worshipping cat people, and a protagonist haunted by ancestral memories of the town’s satanic heyday. Irena Dubrovna (Simone Simon), Anna Karenina-soundalike central character of Cat People, comes from a Serbian village very like Blackwood’s locale; indeed, the main ‘Ancient Sorceries’ Cat Person is a young girl named Ilsé. Lewton originally planned to open with Nazi tanks arriving in Irena’s village, and the invader being attacked at night by a population of werecats, suggesting that the Blackwood tale was first shifted in location before a decision was made to drop his plot and follow Ilsé/Irena – essentially, in Hollywood terms, a ‘Lower Slobovian’ – to New York for a different story.

Whatever the truth, and everyone agrees Koerner gave Lewton the title and ordered him to come up with a film that fit, there are foggy patches. If Koerner believed ‘vampires, werewolves and man-made monsters had been over-exploited’ in 1942, he had a low threshold for repetition, since only the ‘man-made monster’ theme had really become standardised (Chaney, Jr had just made a film with that title). In the sound era, there had been precisely five Hollywood vampire movies8 and only three werewolf films.9 However, there was a precedent for what Lewton would call ‘a cat/werewolf’ film in Erle C. Kenton’s Island of Lost Souls (1932), an adaptation of H. G. Wells’s The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896), though Koerner probably classed it as a ‘man-made monster’ movie, since mad scientist Charles Laughton uses surgery to transform a panther into a woman (Kathleen Burke).

Kenton’s film was one of the ‘US and British horror and suspense movies’ Lewton and Bodeen watched. Lewton later argued for his preferred casting on Cat People by stating

I’d like to have a girl with a little kitten-face like Simone Simon, cute and soft and cuddly and seemingly not at all dangerous. I took a look at the Paramount picture The Island of Lost Souls and after seeing their much-publicized ‘panther woman’, I feel that any attempt to secure a cat-like quality in our girl’s physical appearance would be absolutely disastrous.10

The Lewton team must have screened The Wolf Man, and probably Stuart Walker’s Werewolf of London (1935) too; my guess is that the brief given the producer was not only to come up with a film that fit the Cat People title but to compete with the Universal hit, on a counter-punching level of following up a Wolf Man with a Cat Woman. Most of the criticism on Lewton has tried to distance him from the grubby specifics of the horror genre in 1942,11 but a double-billing of The Wolf Man and Cat People suggests that the latter was developed as an ‘answer’ to the former, at once cashing in on the earlier film and providing a ‘corrective’ to its less successful aspects.12

The competition/inspiration: Lon Chaney Jr in and as The Wolf Man (1941)

Illustrative of this approach is a memo composed by Lewton outlining what he hoped to do with Cat People. He wrote

most of the cat/werewolf stories I have read and all the werewolf stories I have seen on the screen end with the beast gunshot and turning back into a human being after death. In this story, I’d like to reverse the process. For the final scene, I’d like to show a violent quarrel between the man and woman in which she is provoked into an assault upon him. To protect himself, he pushes her away, she stumbles, falls awkwardly, and breaks her neck in the fall. The young man, horrified, kneels to see if he can feel her heart beat. Under his hand black hair and hide come up and he draws back to look in horror at a dead, black panther.13

This is, of course, an inverse of the finale of The Wolf Man, in which just-killed werewolf Larry Talbot (Chaney) transforms into his human self.

Among other carry-overs from The Wolf Man, and even Werewolf of London, to Cat People are animals that instinctively fear the shapeshifter in human form, an apparently explanatory opening quote (The Wolf Man has a dictionary definition of ‘lycanthropy’), a relationship triangle in which the beast person is an outsider (romantic and cultural) who temporarily bewitches one of a longstanding but low-wattage couple, animal tracks that become human footprints and a ‘psychological’ nightmare montage to prefigure the actual metamorphosis. Larry Talbot and Irena Dubrovna are even killed by similar implements: a silver-headed cane and a swordstick (‘this isn’t silver’). Both films, of course, follow the blueprint of most werewolf movies (and many Jekyll and Hyde pictures): a sympathetic but troubled protagonist suffers from a curse which is at once external (due to heredity or the bite of a werewolf) and an expression of their own character contradictions (usually thwarted sexuality). It seems Lewton was less concerned with finding original material than he was with tackling it in an original manner.

The oddest thing Bodeen, T...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- ‘Cat People’

- Afterword: The Curse of the Cat People

- Notes

- Credits

- Bibliography

- eCopyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Cat People by Kim Newman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Médias et arts de la scène & Film et vidéo. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.