![]()

1

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

FROM RUBLEV TO ‘RUBLEV’

Making a biographical film on an historical personage imposes certain expectations on the narrative, such as a linear progression from childhood to death and a focus on the person’s remarkable achievements. In one of his first statements about Andrei Rublev, Tarkovsky boldly stated his intention to flaunt these conventions and seek a new type of narrative:

We would like to depart from traditional dramaturgy with its canonical completedness and with its formal and logical schematism, which so often prevents the demonstration of life’s complexity and fullness. After all, what is the dialectic of the personality? Phenomena which a man encounters or in which he participates become part of the man himself, a part of his sense of life, a part of his character. […] We underestimate the power of the screen image’s emotional charge. In cinema it is necessary not to explain, but to act upon the viewer’s feelings, and the emotion which is awoken is what provokes thought.6

Acting on viewers’ feelings in this way required a complex attitude towards history:

We are not interested in a stylisation of the epoch in costumes, furnishings and the characters’ conversational speech. We want our film to be contemporary not only in the completely contemporary resonance of its main issue. Historical accessories must not fragment the viewers’ attention or try to persuade them that the action is taking place precisely in the fifteenth century. The neutrality of interiors and of costumes (together with their utter authenticity), the landscape and contemporary speech: all of this will help us to speak of what is most important without getting distracted.7

Conscious of the inevitable reductionism of fictional narrative, Tarkovsky takes care to create a world which both characters and viewers can inhabit. This neutrality, or even emptiness, is precisely what allows the film to engage with topical issues and historiographical clichés while retaining the stamp of lived authenticity.

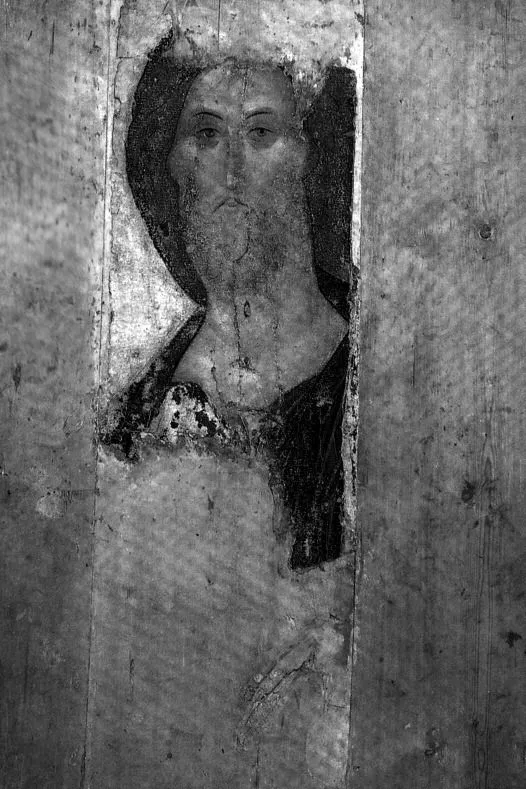

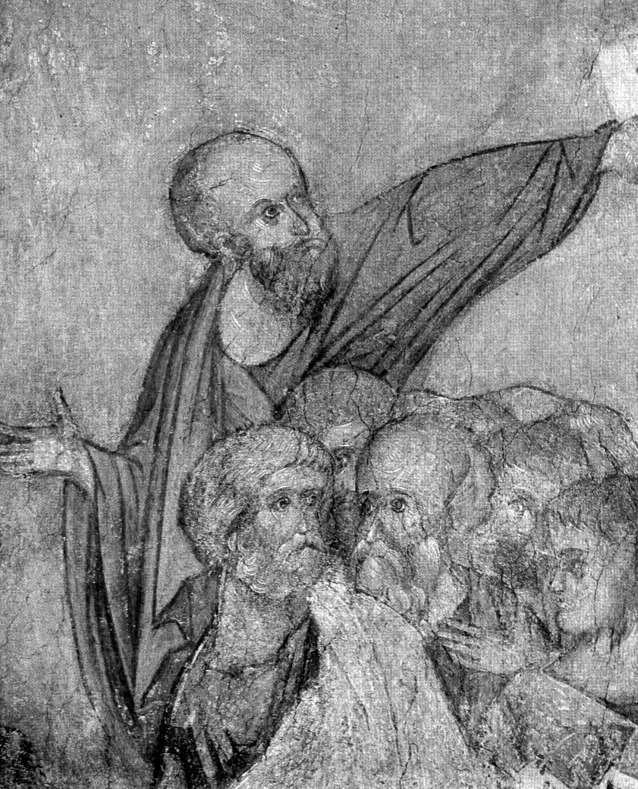

Ostensibly Andrei Rublev is the story of Russia’s most renowned icon painter, who died in 1430 and is conjectured to have been born between 1360 and 1370. Only a single icon, The Old Testament Trinity, can be attributed to Rublev with certainty; its distinctive style has in turn served as the basis for numerous other attributions of icons, frescoes, and miniatures. Sparse contemporary sources record only that Andrei Rublev (pronounced and sometimes written ‘Rublyov’) collaborated in the decoration of several churches in the early 1400s: the Cathedral of the Annunciation in the Moscow Kremlin (spring 1405), the Cathedral of the Dormition in the city of Vladimir (begun 25 May 1408), the new cathedral at Andronikov Monastery to the southeast of Moscow (c. 1410s), and the Trinity Cathedral of the Trinity-St Sergius Monastery to the northeast of Moscow (c. 1420s). Art historians have also detected Rublev’s style in the icons of a church in Zvenigorod, to the west of Moscow, including the renowned Saviour in the Wood; these were recovered from a dilapidated shed in 1918. The episodes of Tarkovsky’s narrative correspond roughly to these events, although his Rublev is never actually shown at work and Rublev’s most amply documented commission at the Trinity Monastery, when he probably created his famous Trinity, features only as a promise at the end of the film.

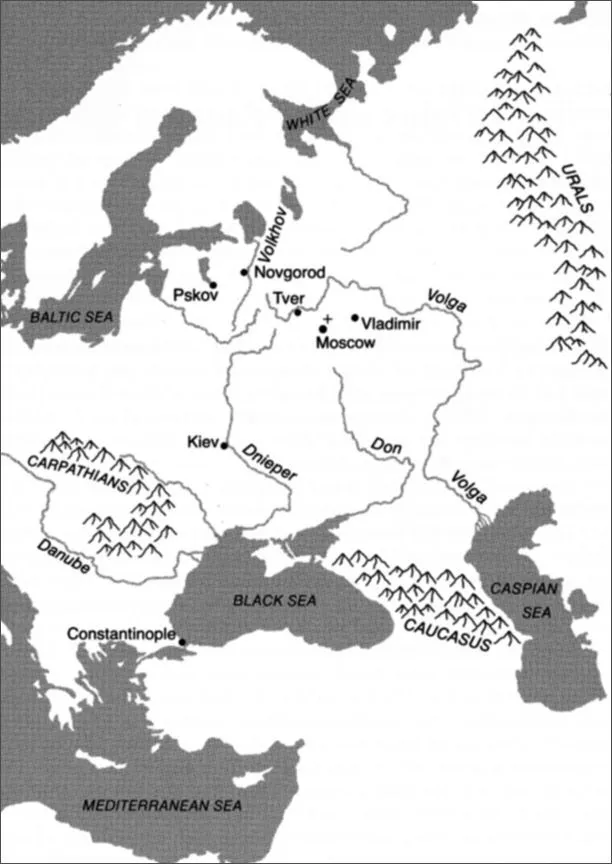

The shape of Andrei Rublev is closely attuned to that of early Russia. By the seventh century the territory was inhabited by a loose group of East Slavonic tribes whose economic activity was centred on the system of waterways which pass from the northern forests to the southern steppes, ‘from the Vikings to the Greeks’. The introduction of Christianity in 988 bonded the tribes into an internationally recognised, Christian state based in Kiev and known as Rus’. Most importantly, Christian belief brought the Bible, the liturgy, and other religious texts in the closely related Church Slavonic language. This language, this script and these texts comprised the cultural patrimony of Rus’, inviolably linking all intellectual culture to the Church. The Church’s unifying role was reinforced when Mongol–Tatar invaders exploited divisions among the hereditary princes to achieve the almost total subjugation of the Russian lands in the early thirteenth century. Power gradually shifted to the cities in the northern forests: Novgorod (a semi-democratic city-state which remained free of Mongol–Tatar domination), Vladimir, and then Moscow. All of this history is reflected to some degree in Andrei Rublev, from the divisive politics of the princes and the vagaries of Mongol–Tatar occupation, to the vital economic role of the river system. Only the pagan rites in the film are clearly anachronistic, coming after four centuries of official Christianity.

Andrei Rublev, Saviour of Zvenigorod deesis row (c. 1410), Tretyakov Gallery (Moscow); Apostles, detail of The Last Judgement (1408), Dormition Cathedral (Vladimir)

Rublev’s life coincided with the beginning of the end of Mongol–Tatar domination and the rise of the modern Russian state, in which the upstart city of Moscow was asserting its primacy among its peers. Vladimir, the previous seat of the Russian Grand Prince and metropolitan (top hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church at the time), lost its dominance to Moscow around 1364. In 1380, the Grand Prince of Moscow Dmitrii Donskoi led the first victory of Russians over the Mongol–Tatar forces at the Battle of Kulikovo Field. Thus, in Andrei Rublev, the Grand Prince is based in Moscow, where he commissions the decoration of Annunciation Cathedral, but he also takes care to show his patronage of Vladimir’s older churches and to replace his burnt, wooden palace with a stone edifice more becoming to the leader of a burgeoning European power. The conflict between the two princes in the film bears a similarity to the rivalry between the sons of Dmitrii Donskoi, Princes Vasilii of Moscow and Iurii of Zvenigorod. While the details of Tarkovsky’s history are not always precise, such rivalries are a recurring motif in the history of Russian city-states, whose princes were forever engaged in musical chairs and mutual destruction.

Early Muscovite Russia, c. 1400

The ‘gathering of the Russian lands’ around Moscow found a spiritual patron in St Sergius of Radonezh (d. 1392). Inspired by a childhood vision, St Sergius became a hermit in the impenetrable Russian forests, but his charismatic presence attracted numerous monks and he founded the Trinity Monastery on the communal or cenobitic model. Many of St Sergius’ disciples founded monasteries on the same model in the Russian north, making him the father of northern Russian monasticism. One such disciple was Andronik (d. 1374), who greatly expanded the monastery which became known by his name, where Andrei Rublev later lived and worked. St Sergius also took an active part in Muscovite politics; in 1380 he gave his blessing to Grand Prince Dmitrii before the landmark Battle of Kulikovo Field. St Sergius is today regarded as the main conduit of Byzantine monastic spirituality in early Muscovite Russia, the heir to Byzantine hesychasm (from the Greek word for silence, hesyché). Hesychast theology, as elaborated by St Gregory Palamas (1296–1359), held that the divine essence was totally transcendent and unknowable, but that the world was suffused with divine energies such as the light seen by the apostles during Christ’s Transfiguration (Mt 17: 1–13). As monks, the hesychasts focused on the acquisition of divine energies through prayer and showed little or no interest in aesthetics. However, the hesychast teaching on the communicability of divine energies inspired contemporaries, who saw the word and the image as media of grace. For instance, Epiphanius the Most-Wise (d. c. 1420) perfected a literary style known as ‘word-weaving’, which was marked by an intense attention to verbal textures. In Andrei Rublev, Kirill cites Epiphanius’ alleged description of St Sergius’ moral virtue, ‘simplicity without ostentation’, precisely as an aesthetic credo.

Whether due to hesychasm or by sheer coincidence, the time of St Sergius witnessed the first blossoming of Muscovite icon painting. The decoration of the cathedral at Trinity Monastery under St Sergius’ successor Nikon became an almost legendary event in the history of Russian spirituality. This is how one anonymous chronicler described it:

the most venerable [Nikon] was overcome with a great wish, and with faith; remaining continuously in this state, he desired to see with his own eyes the church completed and decorated; so he quickly gathered painters, very great men, superior to all others, and perfect in virtue, Daniil by name and Andrei his spiritual brother, and some others with them; and they did the job quickly, as they foresaw in their spirit the death of these spiritual fathers, which would follow soon upon the completion of the task. But since God was helping to complete the venerable one’s task, they devoted themselves to it assiduously and beautified the church with the most diverse paintings, which to this day are capable of astounding viewers. Leaving their final handiwork as a memorial to themselves, the venerable ones remained a short while before the humble Andrei left this life and went to the Lord first, and then his spiritual brother Daniil the most pious, who had lived well with God’s help and who piously accepted a good end in old age. When Daniil was preparing to separate himself from his bodily union, he saw his beloved Andrei, who had preceded him in death, and called out to him in joy. When Daniil saw Andrei, whom he loved, he was filled with great joy and confessed the coming of his spiritual brother to the monks who stood before him, and thus in joy he gave up his spirit to the Lord.8

This unusually detailed passage depicts Rublev and Daniil the Monk (or ‘the Black’, so-called for his monastic cassock) as spiritual brothers, perfect in virtue and superior in artistic ability. In other extant chronicle passages, Rublev is likewise mentioned after his collaborators: Theophanes the Greek, Prokhor of Gorodets, and Abbot Alexander of Andronikov Monastery. About a century later, the Church polemicist Joseph of Volokolamsk (1439–1515) mentioned ‘the famous icon painters Daniil and his pupil Andrei’ as men who had only virtue and were only concerned ‘to be worthy of God’s grace, only to succeed to divine love, […] and always to elevate their mind and thought to the immaterial and divine light, raising their sensible eye to the eternally painted images of Christ Our Lord and His Most-Pure Mother and all the saints’.9 However, it was Rublev’s name alone which became the standard for traditional Moscow-school icon painting. In 1551, in the face of growing Western influence, the Russian church mandated that icons be painted ‘from the ancient standards, as Greek icon painters painted and as Andrei Rublev painted along with other famous icon painters’. Rublev’s exclusive reputation was confirmed in 1988, when he was canonised as a saint on the occasion of the millennium of Christianity in Russia. Today, one can find Rublev mentioned as Russia’s premier theologian in the medieval period, which underscores the experiential and visual nature of Russian spirituality.

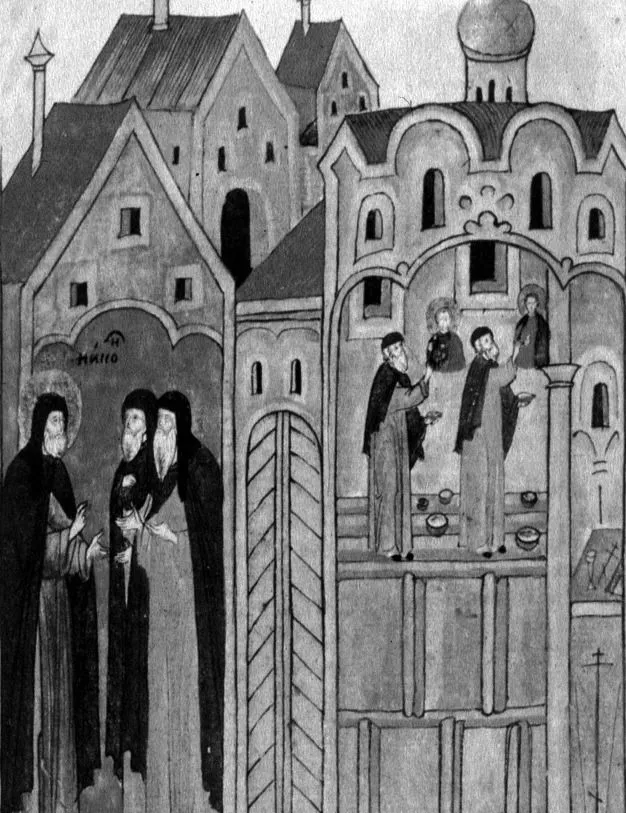

Andrei Rublev and Daniil the Monk in a sixteenth-century manuscript of St Sergius’ Life

Between 1551 and the twentieth...