![]()

CHAPTER

I

Pompey’s Finest Hour?

BIRTHDAY PARADE

September 29, 61 BCE, was the forty-fifth birthday of Pompey the Great. It was also—and this can hardly have been mere coincidence—the second and final day of his mammoth triumphal procession through the streets of Rome. It was a ceremony that put on show at the heart of the metropolis the wonders of the East and the profits of empire: from cartloads of bullion and colossal golden statues to precious specimens of exotic plants and other curious bric-à-brac of conquest. Not to mention the eye-catching captives dressed up in their national costumes, the placards proclaiming the conqueror’s achievements (ships captured, cities founded, kings defeated . . .), paintings recreating crucial moments of the campaigns, and a bizarre portrait head of Pompey himself, made (so it was said) entirely of pearls.1

Over the previous six years, Pompey had dealt decisively with two of the greatest dangers to Rome’s security, and boasted a range of conquests that justified comparison with King Alexander himself (hence the title “the Great”). First, in 67, he had dispatched the pirates who had been terrorizing the whole Mediterranean, with the support of “rogue states” in the East. Their activities had threatened to starve Rome of its sea-borne grain supply and had produced some high-profile victims, including the young Julius Caesar—who, so the story went, managed to raise his own ransom and then proceeded to crucify his captors. Pompey is reputed to have cleared the sea in an impressively (and perhaps implausibly) short three months, before resettling many of the old buccaneers in towns at a safe distance from the coast.

His next target was a more formidable opponent, and another imitator of Alexander, King Mithradates Eupator of Pontus. Some twenty years earlier, in 88 BCE, Mithradates had committed an atrocity that was outrageous even by ancient standards, when he invaded the Roman province of Asia and ordered the massacre of every Italian man, woman, or child that could be found; unreliable estimates by Greek and Roman writers suggest that between 80,000 and 150,000 people were killed. Although rapidly beaten back on that occasion, he had continued to expand his sphere of influence in what is now Turkey (and beyond) and to threaten Roman interests in the East. The Romans had scored a few notable victories in battle; but the war had not been won. Between 66 and 62 Pompey finished the job, while restoring or imposing Roman order from the Black Sea to Judaea. It was a hugely lucrative campaign. One account claims that Mithradates’ furniture stores (“two thousand drinking-cups made of onyx inlaid with gold and a host of bowls and wine-coolers, plus drinking-horns and couches and chairs, richly adorned”) took thirty days to transfer to Roman hands.2

Triumphal processions had celebrated Roman victories from the very earliest days of the city. Or so the Romans themselves believed, tracing the origins of the ceremony back to their mythical founder, Romulus, and the other (more or less mythical) early kings. As well as the booty, enemy captives, and other trophies of victory, there was more lighthearted display. Behind the triumphal chariot, the troops sang ribald songs ostensibly at their general’s expense. “Romans, watch your wives, see the bald adulterer’s back home” was said to have been chanted at Julius Caesar’s triumph in 46BCE(as much to Caesar’s delight, no doubt, as to his chagrin).3 Conspicuous consumption played a part, too. After the ceremonies at the Temple of Jupiter, there was banqueting, occasionally on a legendary scale; Lucullus, for example, who had been awarded a triumph for some earlier victories scored against Mithradates, is reputed to have feasted the whole city plus the surrounding villages.4

At Pompey’s triumph in 61 the booty had flowed in so lavishly that two days, instead of the usual one, were assigned to the parade, and (superfluity always being a mark of success) still more was left over: “Quite enough,” according to Plutarch, in his biography of Pompey, “to deck out another triumphal procession.” The extravagant wealth on display certainly prompted murmurings of disapproval as well as envious admiration. In a characteristic piece of curmudgeon, the elder Pliny, looking back on the occasion after more than a hundred years, wondered exactly whose triumph it had been: not so much Pompey’s over the pirates and Mithradates as “the defeat of austerity and the triumph, let’s face it, of luxury.” Curmudgeon apart, though, it must count as one of the most extraordinary birthday celebrations in the history of the world.5

GETTING THE SHOW ON THE ROAD

Ancient writers found plenty to say about Pompey’s triumph, lingering on the details of its display. The vast quantity of cash trundled through the streets was part of the appeal: “75,100,000 drachmae of silver coin,” according to the historian Appian, which was considerably more than the annual tax revenue of the whole Roman world at the time—or, to put it another way, enough money to keep two million people alive for a year.6 But the range of precious artifacts that Pompey had brought back from the royal court of Mithradates also captured the imagination. Appian again notes “the throne of Mithradates himself, along with his scepter, and his statue eight cubits tall, made of solid gold.”7 Pliny, always with a keen eye for luxury and innovation, harps on “the vessels of gold and gems, enough to fill nine display cabinets, three gold statues of Minerva, Mars and Apollo, thirty three crowns of pearl” and “the first vessels of agate ever brought to Rome.” He seems particularly intrigued by an out-sized gaming board, “three feet broad by four feet long,” made out of two different types of precious stone—and on the board a golden moon weighing thirty pounds. But here he has a moral for his own age and a critical reflection on the consequences of luxury: “The fact that no gems even approaching that size exist today is as clear a proof as anyone could want that the world’s resources have been depleted.”8

In some cases the sheer mimetic extravagance of the treasures on display makes—and no doubt made—their interpretation tricky. One of the most puzzling objects in the roster of the procession was, in Pliny’s words, “a mountain like a pyramid and made of gold, with deers and lions and fruit of all kinds, and a golden vine entwined all around”; followed by a “musaeum” (a “shrine of the Muses” or perhaps a “grotto”) “made of pearls and topped by a sun-dial.” Hard as it is to picture these creations, we might guess that they evoked the exotic landscape of the East, while at the same time instantiating the excesses of oriental luxury.9 Other notable spectacles came complete with interpretative labels. The historian Dio refers to one “trophy” carried in the triumph as “huge and expensively decorated, with an inscription attached to say ‘this is a trophy of the whole world.’”10 This was a celebration, in other words, of Pompey the Great as world conqueror, and of Roman power as world empire.

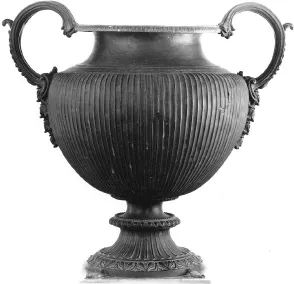

Almost all of these treasures have long since been lost or destroyed: the agate broken, gems recycled into new works of art (or monstrosities, depending on your taste), precious metals melted down and refashioned. But a single large bronze vessel (a krater) displayed in the Capitoline Museum at Rome might possibly have been one of the many on view in the procession of 61 BCE—or if not, then a close look-alike (Fig. 2). This particular specimen is some 70 centimeters tall, in plain bronze, except for a pattern of lotus leaves chased around its neck and inlaid with silver; the slightly rococo handles and foot are modern restorations. It was found in the mid-eighteenth century in the Italian town of Anzio, ancient Antium, and given to the Capitoline Museum—where it currently holds pride of place as the center of the “Hall of Hannibal” (so-called after its sixteenth-century frescoes depicting a magnificently foreign Hannibal perched on an elephant but showing also, appropriately enough, a triumphal procession of an allegorical figure of “Roma” over a captive “Sicilia”).11

FIGURE 2: Bronze vessel, late second-early first century BCE. Originally a gift from King Mithradates to a group of his own subjects (as an inscription around the neck records), it may have reached Italy as part of the spoils of Pompey—a solitary survivor of the treasures on display in his triumphal procession in 61?

The connection with Mithradates is proclaimed by an inscription pricked out in Greek around the rim: “King Mithradates Eupator [gave this] to the Eupatoristae of the gymnasium.” In other words, this was a present from Mithradates to an association named after him “Eupatoristae” (which could be anything from a drinking club to a group involved in the religious cult of the king). It must originally have come from some part of the Eastern Mediterranean where Mithradates had power and influence, and it could have found its way to Antium by any number of routes; but there is certainly a chance that it was one tiny part of Pompey’s collection of booty. It offers a glimpse of what might have been paraded before the gawping spectators in September 61.12

A triumph, however, was about more than costly treasure. Pliny, for example, stresses the natural curiosities of the East on display. “Ever since the time of Pompey the Great,” he writes, “we have paraded even trees in triumphal processions.” And he notes elsewhere that ebony—by which he may well mean the tree, rather than just the wood—was one of the exhibits in the Mithradatic triumph. Perhaps on display too was the royal library, with its specialist collection of medical treatises; Pompey was said to have been so impressed with this part of his booty that he had one of his ex-slaves take on the task of translating it all into Latin.13 Many other items had symbolic rather than monetary value. Appian writes of “countless wagonloads of weapons, and beaks of ships”; these were the spoils taken directly from the field of conflict, all that now remained of the pirate terror and Mithradates’ arsenal.14

Further proof of Pompey’s success was there for all to contemplate on the placards carried in the procession (see Figs. 9 and 28). According to Plutarch, they blazoned the names of all the nations over which he triumphed (fourteen in all, plus the pirates), the number of fortresses, cities, and ships he had captured, the new cities he had founded, and the amount of money his conquests had brought to Rome. Appian claims to quote the text of one of these boasts; it ran, “Ships with bronze beaks captured: 800. Cities founded: in Cappadocia 8; in Cilicia and Coele-Syria 20; in Palestine, the city which is now Seleucis. Kings conquered: Tigranes of Armenia, Artoces of Iberia, Oroezes of Albania, Darius of Media, Aretas of Nabatea, Antiochus of Commagene.”15

No less an impact can have been made by the human participants in the show: a “host of captives and pirates, not in chains but dressed up in their native costume” and “the officers, children, and generals of the kings he had fought.” Appian numbers these highest ranking prisoners at 324 and lists some of the more famous and evocative names: “Tigranes the son of Tigranes, the five sons of Mithradates, that is, Artaphernes, Cyrus, Oxathres, Darius, and Xerxes, and his daughters, Orsabaris and Eupatra.” For an ancient audience, this roll-call must have brought to mind their yet more famous namesakes and any number of earlier conflicts with Persia and the East: the name of young Xerxes must have evoked the fifth-century Persian king, best known for his (unsuccessful) invasion of Greece; Artaphernes, a commander of the Persian forces at the battle of Marathon. The names alone serve to insert Pompey into the whole history of Western victory over Oriental “barbarity.”16

An impressive array of captives made for a splendid triumph. By some clever talking, Pompey is said to have managed to get his hands on a couple of notorious pirate chiefs who had actually been captured by one of his Roman rivals, Quintus Caecilius Metellus Creticus, who had been hoping to show them off in his own triumphal parade. At a stroke, Pompey had robbed Metellus’ triumph of two of its stars, while enhancing the line-up in his own.17 Even so, some of the defeated were unavoidably absent. Tigranes père of Armenia, Mithradates’ partner in crime, had had a lucky escape. Thanks to a well-timed surrender, he was restored by Pompey as a puppet ruler on his old throne and did not accompany his son to the triumph. (In the treacherous world of Armenian politics, young Tigranes had actually sided with the Romans, before disastrously quarreling with Pompey and ending up a prisoner.) Mithradates himself was already dead. He was said to have forestalled the humiliation of display in the triumph by his timely suicide; or rather he had a soldier kill him, his long-term precautionary consumption of antidotes having rendered poison useless.18

In place of Tigranes and Mithradates themselves, “images”—eikones in Appian’s Greek—were put on display. Almost certainly paintings (though three-dimensional models are known in other triumphs), these were said to capture the crucial moments in the conflict between Romans and their absent victims: the kings were shown “fighting, beaten and running away . . . and finally there was a picture of how Mithradates died and of the daughters who chose to die with him.” For Appian, these images reached the very limits of realistic representation, depicting not only the cut and thrust of battle and scenes of suicide but even, as he notes at one point, “the silence” itself of the night on which Mithradates fled. Thanks to triumphal painting of this type, art historians have often imagined the triumph as one of the driving forces behind the “realism” that is characteristic of many aspects of Roman art.19

Pompey himself loomed above the scene, riding high in a chariot “studded with gems.” Parading ...