![]()

1

CHARTER GENERATIONS

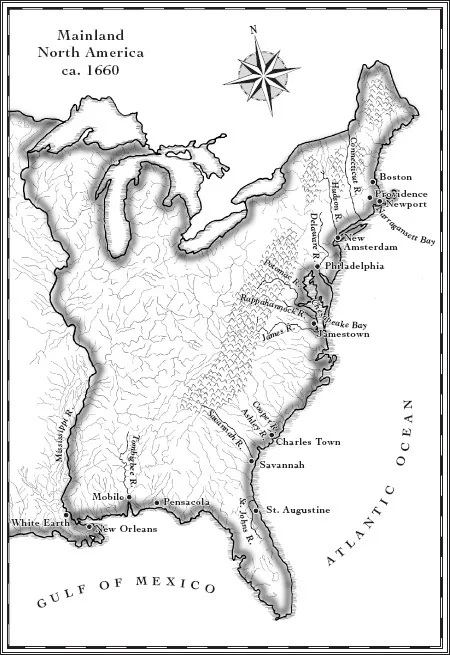

BLACK LIFE on mainland North America originated not in Africa or America but in the nether world between the two continents. Along the periphery of the Atlantic—first in Africa, then Europe, and finally in the Americas—it was a product of the momentous meeting of Africans and Europeans and then their equally fateful rendezvous with the peoples of the New World. Although the countenances of these “Atlantic creoles” might bear the features of Africa, Europe, or the Americas in whole or part, their beginnings, strictly speaking, were in none of those places.1 Instead, by their experience and sometimes by their person, they had become part of the three worlds that came together in the Atlantic littoral. Familiar with the commerce of the Atlantic, fluent in its new languages, and intimate with its trade and cultures, they were cosmopolitan in the fullest sense.

Atlantic creoles traced their beginnings to the historic encounter of Europeans and Africans on the west coast of Africa. Many served as intermediaries, employing their linguistic skills and their familiarity with the Atlantic’s diverse commercial practices, cultural conventions, and diplomatic etiquette to mediate between the African merchants and European sea captains. In so doing, some Atlantic creoles identified with their ancestral homeland (or a portion of it)—be it African or European—and served as its representatives in negotiations. Other Atlantic creoles had been won over by the power and largess of one party or another, so that Africans entered the employ of European trading companies, and Europeans traded with African potentates. Yet others played fast and loose with their mixed heritage, employing whichever identity paid best. Whatever strategy they adopted, Atlantic creoles began the process of integrating the icons and beliefs of the Atlantic world into a new way of life.2

The emergence of the Atlantic creoles was only a tiny outcropping in the massive social upheaval that joined the peoples of the eastern and western hemispheres. But it was representative of the small beginnings that initiated the monumental transformations, as the new people of the Atlantic soon made their presence felt. Some traveled broadly as blue-water sailors, supercargoes, interpreters, and shipboard servants. Others were carried to foreign places as exotic trophies to be displayed before curious publics eager for a glimpse of the lands beyond the sea. Some were even sent to distant shores with commissions to master the ways of the newly discovered “other” and retrieve the secrets of their knowledge and wealth. A few entered as honored guests, took their place in royal courts as esteemed councilors, and married into the best families.3

Atlantic creoles first emerged around the trading factories or feitorias established along the coast of Africa in the fifteenth century by European expansionists. Finding trade more lucrative than pillage, the Portuguese Crown began sending agents to oversee its interests in Africa. These official representatives were succeeded in turn by private entrepreneurs, or lançados, who, with the aid of African potentates, established themselves sometimes in competition with the Crown’s emissaries. Portuguese competitors were soon joined by other European nations, and the coastal factories became a commercial rendezvous for all manner of transatlantic traders. What was true of the nominally Portuguese enclaves also held for those later established or seized by the Dutch (Fort Nassaw and Elmina), Danes (Fredriksborg and Christianborg), Swedes (Carlsborg), French (St. Louis), and English (Fort Kormantse).4

The growth of the small fishing villages along Africa’s Gold Coast during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries suggests something of the change that followed the arrival of European traders. Between 1550 and 1618, Mouri (where the Dutch constructed Fort Nassaw in 1612) grew from a village of 200 people to 1,500 and then to an estimated 5,000 to 6,000 at the end of the eighteenth century. In 1555, Cape Coast counted only twenty houses; by 1680 it had 500 or more. Axim, which had 500 inhabitants in 1631, expanded to between 2,000 and 3,000 by 1690. Among the African fishermen, craftsmen, village-based peasants, and laborers attached to these villages were an increasing number of Europeans. Although the mortality and transiency rates in these enclaves were extraordinarily high even by the standards of early modern port cities, permanent European settlements developed from the corporate employees, merchants and factors, stateless sailors and soldiers, skilled craftsmen, occasional missionaries, and sundry transcontinental drifters.5

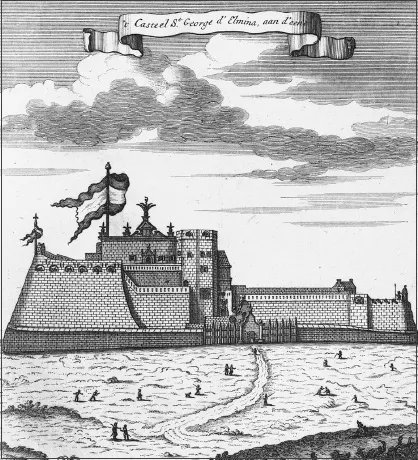

Established in 1482 by the Portuguese and captured by the Dutch in 1637, Elmina was one of the first of these factories and a model for those that followed. A meeting place for African and European commercial ambitions, Elmina—the Castle São Jorge da Mina and the town that surrounded it—became headquarters of the Portuguese and later Dutch mercantile activities on the Gold Coast and, with a population of 15,000 to 20,000 in 1682, the largest of some three dozen European outposts in the region.6

The peoples of the enclaves—long-term residents and wayfarers alike—soon joined together, geographically and genetically. European men took wives and mistresses among African women, and before long the children born of these unions helped people the enclave. Elmina sprouted a substantial cadre of Euro-Africans (most of them Luso-Africans), men and women of African birth but shared African and European parentage, whose swarthy skin, European dress and deportment, acquaintance with local norms, and multilingualism gave them an insider’s knowledge of both African and European ways but denied them full acceptance in either culture. By the eighteenth century, they numbered several hundred in Elmina. Along the Angolan coast they may have been even more numerous.7

People of mixed ancestry and tawny complexion composed but a small fraction of the population of the coastal factories, but few observers failed to note their existence—which itself gave their presence a disproportionate significance. Africans and Europeans alike sneered at the creoles’ mixed lineage and condemned them as haughty, proud, and overbearing. When they adopted African ways, wore African dress and amulets, or underwent circumcision and scarification, Europeans declared them outcasts (tangosmaos or reneges to the Portuguese). When they adopted European ways, wore European clothing and crucifixes, employed European names or titles, and comported themselves in the manner of “white men,” Africans denied them the right to hold land, marry, and inherit property. Although the tangosmaos faced reproach and proscription, all parties conceded that the creoles were shrewd traders. Their reputation attested to their mastery of the fine points of intercultural negotiations and the advantage in dealing with these knowledgeable entrepreneurs. Despite their defamers, some rose to positions of wealth and power, compensating for their lack of lineage with knowledge, skill, and entrepreneurial derring-do.8

Not all tangosmaos were of mixed ancestry, and not all people of mixed ancestry were tangosmaos. Color was only one marker of this culture-in-the-making, and generally the least significant one.9 From common experience, conventions of personal behavior, and cultural sensibilities compounded by shared ostracism, Atlantic creoles acquired interests of their own, apart from those of their European and African antecedents. Of necessity, they spoke a variety of African and European languages, weighted strongly toward Portuguese. But from the seeming babble emerged a pidgin lingua franca that enabled Atlantic creoles to communicate with all. In time, their pidgin evolved into a creole, borrowing its vocabulary from all parties and creating a grammar unique unto itself. Derisively called fala de Guine or fala de negros—literally “Guinea speech” or “Negro Speech”—by the Portuguese and black Portuguese by others, this creole lingua franca became the language of the Atlantic.10

Although jaded observers condemned the culture of the enclaves as nothing more than “whoring, drinking, gambling, swearing, fighting, and shouting,” Atlantic creoles attended church (usually Roman Catholic), married according to the sacraments, raised children conversant with European norms, and drew a livelihood from their knowledge of the Atlantic commercial economy. In short, they created societies of their own, of but not always in the societies of the Africans who dominated the interior trade and the Europeans who controlled the commerce of the Atlantic. By the mid-nineteenth century, they would station themselves on all corners of the Atlantic world, establishing branches of their families in Europe and the Americas so their children felt as comfortable in Bahia as in Birmingham, Lisbon as in Lagos. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, however, their world centered on the Atlantic itself.

Operating under European protection, always at African sufferance, the enclaves developed governments with a politics as diverse and complicated as the peoples who populated them. Their presence created political havoc, enabling new men and women of commerce to gain prominence and threatening older, often hereditary hierarchies. Intermarriage with established peoples allowed creoles to fabricate lineages that gained them full membership in local elites, something that creoles eagerly embraced. The resultant political turmoil promoted state formation along with new class relations and ideologies.11

New religious forms emerged and then disappeared in much the same manner, as Europeans and Africans brought to the enclaves not only their commercial and political aspirations but all the trappings of their cultures as well. Priests and ministers sent to tend European souls made African converts, some of whom saw Christianity as a way to both ingratiate themselves with their trading partners and gain a new truth. Missionaries sped the process of Christianization and occasionally scored striking successes. At the beginning of the sixteenth century, the royal house of Kongo converted to Christianity. Catholicism, in various syncretic forms, infiltrated the posts along the Angolan coast and spread northward. Islam filtered in from the north.

Whatever the sources of the new religions, most converts saw little cause to surrender their own deities. They incorporated Christianity and Islam to serve their own needs and gave Jesus and Mohammed a place in their spiritual pantheon. New religious practices, polities, and theologies emerged from the mixing of Christianity, Islam, and polytheism. Similar syncretic formations influenced the agricultural practices, architectural forms, and sartorial styles as well as the cuisine, music, art, and technology of the enclaves. Like the stone fortifications that greeted visitors, these cultural innovations announced the presence of something new to those arriving on the African coast, whether they traveled by caravan from the interior or sailed by caravel from the Atlantic.12

The business of the creole communities was trade—brokering the movement of goods through the Atlantic world. Although island settlements such as Cape Verde, Principé, and São Tomé developed indigenous agricultural and sometimes plantation economies, the comings and goings of African and European merchants dominated life even in the largest of the creole communities, which served as both field headquarters for great European mercantile companies and collection points for trade between the African interior and the Atlantic littoral. Depending on the location, the exchange involved European textiles, metalware, guns, liquor, and beads for African gold, ivory, hides, pepper, beeswax, and dyewoods. The coastal trade or cabotage added to the mix. Everywhere, slaves were bought and sold, and over time the importance of commerce-in-persons grew.

As societies engaged in the trade in slaves, the coastal enclaves became societies with slaves. African slavery in its various forms—from pawnage to chattel bondage—was practiced in these towns. Both Europeans and Africans held slaves, imported and exported them, hired them, used them as collateral, and traded them. At Elmina, the Dutch West India Company owned some 300 slaves in the late seventeenth century, and individual Europeans and Africans held others. Along with slaves appeared the inevitable trappings of that particular form of domination—overseers to supervise slave labor, slave catchers to retrieve runaways, soldiers to keep order and guard against insurrections, and officials to adjudicate and punish transgressions beyond a master’s reach. Freedmen and freedwomen, who had somehow escaped bondage, also enjoyed a considerable presence. Former slaves mixed Africa and Europe culturally and sometimes physically.13

Mirroring developments on the coast of Africa, a cadre of Atlantic creoles emerged in Europe. By the mid-sixteenth century, some ten thousand black people lived in Lisbon, where they composed about 10 percent of the population. Seville had a slave population of 6,000 (including a minority of Moors and Moriscos). As the centers of the Iberian slave trade, these cities distributed African slaves throughout Europe. Many found their way to the most distant corners of the continent. By the end of the sixteenth century, they were numerous enough in England for Elizabeth to order their expulsion from the kingdom.14

Whether they resided in Europe or Africa, it was knowledge and experience far more than color that set the Atlantic creoles apart from the Africans who brought slaves from the interior and the Europeans who carried them across the Atlantic, on one hand, and the hapless men and women upon whose commodification the slave trade rested, on the other. Maintaining a secure place in such a volatile social order was not easy. The Atlantic creoles’ liminality, particularly their lack of identity with any one group, posed numerous dangers. While their intermediate position made them valuable to African and European traders alike, it also made them vulnerable: they could be ostracized, scapegoated, and on occasion enslaved. Maintaining independence amid the shifting alliances between and among Europeans and Africans was always difficult. Inevitably, some failed.

Debt, crime, heresy, immorality, official disfavor, or bad luck could mean enslavement—if not for the great traders, at least for those on the fringes of the creole community.15 Placed in captivity, Atlantic creoles might be exiled anywhere around the Atlantic—the islands along the coast, the European metropoles, or the plantations of the New World. In the seventeenth century and the early part of the eighteenth, most slaves exported from Africa went to the sugar plantations of the Atlantic islands and the Americas. Enslaved Atlantic creoles might be shipped to Pernambuco, Barbados, or Martinique and later Jamaica and Saint Domingue—all expanding centers of New World staple production. But transporting them to these hubs of the plantation economy posed dangers, which American planters well understood. The distinguishing characteristics of Atlantic creoles—their linguistic dexterity, cultural plasticity, and social agility—were precisely those qualities that the sugar planters of the New World feared the most. For their labor force, planters desired youth and strength, not experience and wisdom. Too much knowledge might be subversive to the good order of the plantation.

Simply put, men and women who understood the operations of the Atlantic system, including the slave trade, were too dangerous to be trusted in the human tinderboxes created by the sugar revolution. Rejected by the most prosperous New World regimes, Atlantic creoles were frequently exiled to marginal slave societies where woul...