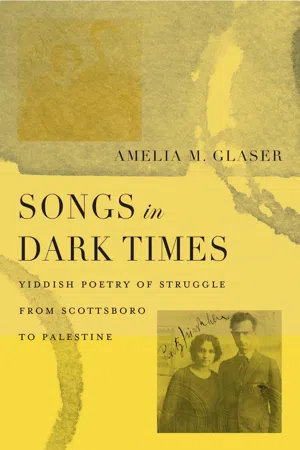

Songs in Dark Times

Amelia M. Glaser

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Songs in Dark Times

Amelia M. Glaser

About This Book

A probing reading of leftist Jewish poets who, during the interwar period, drew on the trauma of pogroms to depict the suffering of other marginalized peoples. Between the world wars, a generation of Jewish leftist poets reached out to other embattled peoples of the earth—Palestinian Arabs, African Americans, Spanish Republicans—in Yiddish verse. Songs in Dark Times examines the richly layered meanings of this project, grounded in Jewish collective trauma but embracing a global community of the oppressed.The long 1930s, Amelia M. Glaser proposes, gave rise to a genre of internationalist modernism in which tropes of national collective memory were rewritten as the shared experiences of many national groups. The utopian Jews of Songs in Dark Times effectively globalized the pogroms in a bold and sometimes fraught literary move that asserted continuity with anti-Arab violence and black lynching. As communists and fellow travelers, the writers also sought to integrate particular experiences of suffering into a borderless narrative of class struggle. Glaser resurrects their poems from the pages of forgotten Yiddish communist periodicals, particularly the New York–based Morgn Frayhayt ( Morning Freedom ) and the Soviet literary journal Royte Velt ( Red World ). Alongside compelling analysis, Glaser includes her own translations of ten poems previously unavailable in English, including Malka Lee's "God's Black Lamb, " Moyshe Nadir's "Closer, " and Esther Shumiatsher's "At the Border of China."These poets dreamed of a moment when "we" could mean "we workers" rather than "we Jews." Songs in Dark Times takes on the beauty and difficulty of that dream, in the minds of Yiddish writers who sought to heal the world by translating pain.

Frequently asked questions

Information

1

Esther Shumiatcher’s Travels

| Ver yomtevt do, ver yomtevt do, ba aykh | Who is celebrating, who is celebrating with you | |

|---|---|---|

mit fonen nonte in yeder fester hant? | With familiar flags in that sturdy hand? | |

O, es geyen do di reyen. Vi der friling af ayer taykh! | Oh, the columns advance. Like spring on your river! | |

| —S’iz May, s’iz ershter May, o do in land!2 | Oh it’s May, it’s May First, here in this land! |

| Un ven likht | And when light | |

| vert in tunkl dertrunken— | Drowns in darkness | |

| zenen khvalyes | The waves are | |

| dayn heym, | your home, | |

| zenen khvalyes | The waves are | |

| dayn bet.6 | Your bed. |