![]()

PART I

States and Peoples

![]()

1

Wartime Societies and Shelter Politics in National Socialist Germany and Britain*

Dietmar Süss

The art of war changed fundamentally from the beginning of the twentieth century with the introduction of aircraft, which brought new possibilities for destruction and new forms of death. Air power thus belongs to the specific form of power exercised by modern societies in the twentieth century. This contribution, like much recent military history, deals with ‘war as a condition of society’1 and thus also with the cultural and existential ways in which bombing was managed in Germany and Great Britain. At the centre stand two very differently constructed political systems, British democracy and National Socialist dictatorship, and the question of the specific and common features they employed in overcoming and appropriating the experience of bombing. In the First World War, both Germany and Great Britain, two highly industrialized nations, had already exploited the new military possibilities then available by dropping bombs on enemy cities. For a long time systematic conceptual comparisons in the tradition of historical-comparative method were out of favour, standing in the shadow of the theoretical battles during the Cold War over the weight to be attached to the concept of totalitarianism. If it was done at all, it was fascism and communism that served as foils for the comparative analysis of totalitarian power, but not democracies like Britain, Sweden or the United States. Only since the late 1970s have attempts been made to compare National Socialism with liberal democracies as elements of the broader crisis of modernity – not in order to relativize them but in order to examine precisely the convergences, differences and the potential for contradiction within and between modern societies.2 The bulk of the comparison here consists of establishing exact observations on the internal structure of dictatorship and democracy under a permanent state of emergency. In the first place, such a perspective allows the air war to be analysed as a European phenomenon and as a part of the age of total war, without having to follow the German-British controversies over the political-moral blame for the bombing war which have dominated debates from the war down to the present. Second, the comparison makes possible answers to the question about what the core of the ‘people’s community’ in war represented; with an eye on the British experience, it shows the specific mix of factors made up of National Socialist integration and power, of mobilization and terror; and finally, it becomes possible, according to both the system-specific and system-independent answers to the threat from the air, to ask: was the organization of air defence and bunker life something specifically ‘National Socialist’? Were the strategies and interpretative models, rituals and myths of community solidarity demonstrated in other industrial societies in a similar way and were there parallel answers to the threat from the air? Was there a conception independent of any political system to protect the civilian population in war and to destroy the morale of the enemy?

My central thesis can be expressed thus: the ‘emergency’ of the air war inspired equally in both Great Britain and Germany the mythical ‘supercharging’ of the wartime experience as a national community of fate and as the normative form of civilian behaviour. The study and observation of ‘war morale’ were part of the power to define who did or did not belong to the people or the nation and was thus a central field of social conflict. These considerations are dealt with in this contribution through the example of the organization of shelter life in Germany and Great Britain. The temporary dispersal of wartime society under the earth signified a massively dynamic mobilization of urban daily life. In the bunkers and galleries the war showed itself to be ‘war as a condition of society’ in a deeper way. Bunkers were spaces in which dictatorship and democracy exercised control and disciplined behaviour. They were an object of propaganda, sites for the promise of protection and the establishment of normative gender roles. Even though the instruments of state repression were less clearly marked in Great Britain than in Germany, there is much to indicate that the contemporary strategies of crisis management were evidently not system-specific but were to a certain extent an expression of the dynamic involvement of society in the conduct of industrialized warfare.

These issues are examined here in three steps. First, the differing interpretations of what the building of bunkers and air defences signified for both wartime societies are addressed, while at the same time discussing the differing expectations and conceptions of war as ‘a condition of society’. In the second section questions are posed about power, dominance and security in the social practice of wartime societies dispersed underground. How was access to the bunkers regulated? What role did power and the social regimentation of behaviour play in the organization of the ‘home front’? The third section looks at the relationship in shelter life between normative behaviour, health provision and controls. In both wartime societies bunkers were also regarded as places which posed a threat to public order and which constituted a danger-point for outbreaks of disease. How did both states react to this very similar alleged danger and what was the significance of gender-specific stereotypes about ‘female’ behaviour in wartime?

impending apocalypse

Air-raid shelters were the internal bulwark against an external threat. They were meant to offer protection against the weapons of modern war, both gas and bombs. Yet their significance in propaganda terms extended far beyond deep bunkers and sturdy cellars. From the start of the war the social structure of the shelter held a special interest for Germany and Great Britain; overcoming individual fears and maintaining collective order was a basic precondition for the protection of ‘war morale’ and thus for the nation’s fight for survival.3 Indeed, in Germany well before the start of the war there was much public discussion about air-raid protection,4 though in practice construction measures remained far behind the expectations of planners. The reason lay first of all in the logic of contemporary warfare, in which everything had been anticipated except a lengthy bombing campaign. The first British air attacks in 1940 caused consternation, and in Berlin it came to be recognized that the loyalty of the national comrades (Volksgenossen) could only be maintained in the long term if people were given permanent protection from attacks. A few months after the adoption of the ‘Immediate Führer Programme’ for the construction of bomb-safe air-raid shelters on 10 October 1940, the chief of air-raid protection in the Reich Air Ministry, Kurt Knipfer, outlined his vision of future bunker policy.5 The construction programme was from the outset bound up with grand ambitions: women and children were to be protected, and at the same time arrangements made to safeguard armaments workers. Night-time security was designed to buy day-time productivity.

In the winter of 1941/2 it was already clear that such an ambitious programme would be a fiasco. This outcome was all the more dangerous because in several respects bunkers performed a central function for the morale of the population and thus for the self-understanding of the ‘people’s community’ (Volksgemeinschaft) at war. In the end both the internal and external form of the bunkers was supposed to reflect the military strength and the martial outlook of the nation: they were spaces in which the ordered structure of National Socialist society maintained its wartime complexion – as a struggle for membership of ‘the community’, as a pledge of protection by the Third Reich and as a blueprint for the future of a new National Socialist society.6

‘Fortresses and castles in times past,’ maintained Germany’s Plenipotentiary General for Construction in 1942,

The design of the bunkers, too, was not merely functional. Far more was intended to be displayed: the past and present of the Volksgemeinschaft, whose architectural showpieces were symbols of the unrestrained will to survive. At the end of the war the tall, undamaged tower shelters would not only be proof of success, but would also stand for the future as an expression of the creative ingenuity of the Volksgemeinschaft, and would thus be part of a new, well-fortified National Socialist city.

As early as 1941, town planners in Hamm in Westphalia began to integrate the projects for the construction of shelters into a master concept of urban development, as they did in other cities built on medieval models.8 Nine tower shelters along the old ring wall enclosing the town centre would turn the town into an impregnable fortress and transform the inhabitants into fighting citizens defending themselves against the robber barons of the air. But by the autumn of 1943, it was clear that the grandiose plans had foundered because of a lack of resources and because of the force of Allied air attacks on Europe’s largest marshalling yard, and that shelter spaces were available for only a fraction of the population. Instead of tower shelters, the city went over to constructing tunnels and private air-raid shelters and to the creation of as many underground shelter spaces as possible.

In Hanover town planners considered moving substantial parts of the urban infrastructure underground; a ‘bunkered’ city would emerge, combining the vision of a well-fortified medieval town with the extensive conversions of modern National Socialist architecture, one that entirely breathed the architectural spirit of Albert Speer.9 In the first two years of building work, shelters and their large construction sites developed into central locations of self-assurance regarding the protective function of the National Socialist state.10 Nothing unfortunate could happen, it was argued, if at the initiative of the Führer, the threatened security of the population was rapidly and decisively safeguarded and shelter space actively created. Nevertheless this staged security was a double-edged sword, since on the one hand such public rituals documented the ability of the Volksgemeinschaft to put up a fight, while on the other hand they were also, as a direct result of the duration of the war, the mirror image of internal vulnerability. Thus it was no surprise that from 1942 onwards, images of the first ground-breaking ceremonies for the planned bunkers disappeared once again from public view.

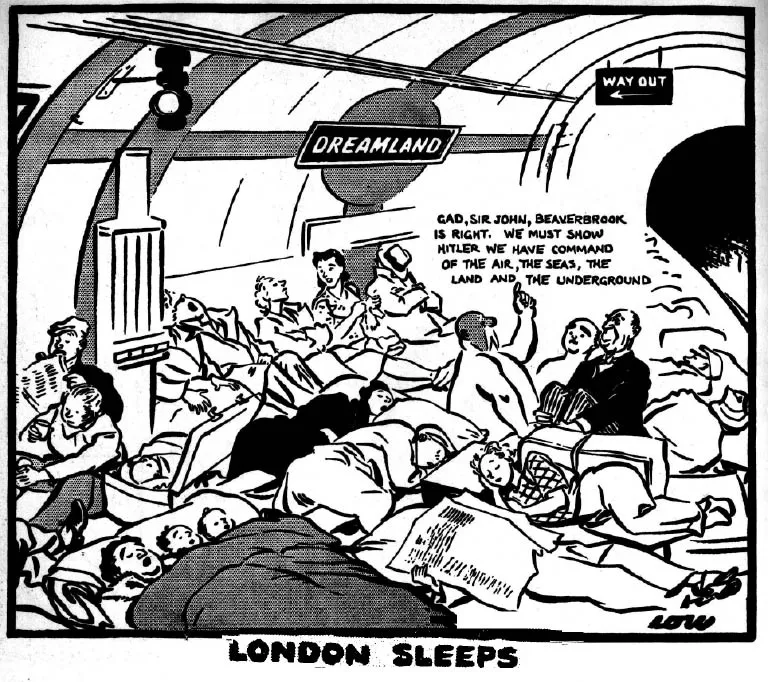

In Great Britain, however, a comparable shelter programme never existed, neither before the war nor during it; the mass production of individual shelters was preferred over larger tunnels or bunkers above ground. This choice was not without risk, for the situation dramatically intensified with the first heavy bombings of London in September 1940; the feared losses did not in fact arise, but it was soon clear that the existing capacities in the shelters themselves were insufficient even if a majority of Londoners did not use them and only a minority actually sought mass accommodation. Life in the shelters was not regarded, as it was in Germany, as a national fate. At the start of the attacks many sought shelter in public buildings, in churches and schools, but not in the London Underground, which at the outbreak of war was not at first intended as a place of refuge. On the contrary: the ministries were convinced that under no circumstances could the tube be occupied or blocked by masses of people.11 It was a pivotal means of transport at the heart of public infrastructure and therefore particularly vulnerable. This attitude changed as the scale of the damage and the discontent of the population grew ever greater with the expansion of the attacks. The government was accused of being unable to provide sufficient protection. The tube tunnels were opened under considerable public pressure.12 The construction of shelters, hygienic conditions in mass accommodation, safety precautions and escape routes, supplies of food and water, the announcement of opening times and the effectiveness of the air-raid warning systems, all became by at least the late summer of 1940 a flashpoint for internal political conflict, with the state’s capacity for crisis management at the centre.

‘London sleeps’. Cartoon by David Low, Evening Standard, 24 September 1940. Courtesy of Associated Newspapers Ltd.

Thus it was not in the end decisive how many people actually sought out the shelters: the important thing was that shelter spaces lay at the intersection of various conflicts, whose origins reached back into the pre-war era, but which experienced a noticeable radicalization during and because of the war. These issues included the state’s fear of the political unreliability of the working class as well as the social conflicts discernible during evacuation, which resulted from the class character of British society. The squalor of workers’ housing in the major cities had been the subject of fierce polemics for some time. Journalists and writers had again and again complained about such conditions. After the conflicts over evacuation, shelters too became a further site where the social tinderbox threatened to ignite.

Life underground, the conditions of protection and supply, of welfare and state assistance were part of an ever more intense debate from 1940 over the state of the nation, over the meaning of the conflict with fascist Germany and the hope for a ‘New Jerusalem’13 that would bring the material freedom that had eluded the working class for so long. In this respect, conditions in air-raid shelters afforded not only the external manifestation of the necessity for reform but also the material basis for social conflict. The response to such conditions thus became an acid test of the authorities’ readiness to implement serious social improvements – an impulse that had nothing to correspond to it in the Third Reich, for in the end German bunkers were sites to secure dominance and not really zones in which a just post-war order could be publicly discussed.

Power, Dominance, Security: Shelters as New Sites of the War on the German Home Front

Order and dominance were thus the central categories in which, especially in Germany, the future of air defence was debated. Although the necessity for building shelters was very different in the Third Reich and in Great Britain, not least because of the different intensity of the air war, nevertheless the bunkers and tube tunnels in both wartime societies were treated as an important test case for the capacity of both political systems to produce security for the population and therefore to legitimate their rule. There was also something else, which belonged to the core problem of the wartime mobilization of the nation and showed the extent to which the character of the air war experience embraced the whole sy...