![]()

1 mHealthy Behaviors

Engaging researchers and practitioners in a facilitated dialogue on mobile-mediated health behavior change

Patricia Mechael, mHealth Alliance at the UN Foundation and Earth Institute at Columbia University Jonathan Donner, Microsoft Research

Introduction

From diagnostics to disease surveillance to telemedicine, there is an explosion of interest regarding the application of mobile communication technologies to support health initiatives. One topic garnering particular enthusiasm is the use of mobile telephones to support and promote healthy behaviors and to prevent unhealthy behaviors. These behavioral support and change initiatives are particularly challenging (and promising) when applied to resource-constrained settings where other forms of outreach and messaging are not cost-effective, and where few other channels for customized outreach (digital or otherwise) are available. In the first decade of the twenty-first century, billions of people have purchased the first telephone of their lives – clearly there are opportunities to leverage these new connections for public health.

As mobile phone-based health promotion activities and campaigns increase in scale and momentum, understanding the pathways to behavior change and the role of mobile technology is essential. This is not simply an abstract theoretical exercise, but rather a matter of immediate practical concern as programs need to be developed, protocols approved, and change pursued. Yet it seems that there are few opportunities for exchange of information and proven practice between practitioners and researchers. At the moment, there is limited knowledge among practitioners on best practices and how best to optimize or evaluate the role of mobile-mediated interactions as they relate to health behavior change.

To support this need, the Technology for Emerging Markets Group (TEM) at Microsoft Research India and the Center for Global Health and Development (CGHED) at the Earth Institute at Columbia University hosted a workshop and roundtable in London, from 16 to 17 December 2010, called mHealthy Behaviors: using mobile phones to support and promote healthy behaviors in the developing world. Travel support was provided by MSR India and a generous grant from the GSMA Development Fund, with extensive additional technical support provided by CGHED. The first day of the event was an open session held in conjunction with the 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development (ICTD2010) conference at Royal Holloway Campus of the University of London1. The second day was a closed-door roundtable hosted by London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Representing mobile-mediated behavioral change and support projects in Latin America, Africa, Europe, and South Asia, the contributors included mHealth practitioners from NGOs and the private sector, as well as researcher/practitioners from leading academic institutions.

The first goal of the sessions was to give practitioners an opportunity to make their implicit change models regarding the use of mobile technologies for behavior change and health promotion explicit, and to identify best practices for implementation as well as research priorities for the future. The second goal was to begin to craft the chapters in this volume.

The conversations in the United Kingdom and the accompanying background papers provided the basis for the original chapters on mobile-enabled behavioral change included in this volume. For some of our authors, this was a rare opportunity to document their experiences for their colleagues in the mHealth field, to explore behavior change and communication models, and to position their experiences within the context of other programs and research of relevance to their areas of practice. In other cases, behavioral researchers and epidemiologists working in the areas of mHealth and behavior change were engaged to share their own learning on what is working or not when it comes to evaluating the impact of such programs.

The domain of mediated behavior change is, of course, not new. There is a rich tradition of research and practice of mass media behavior change campaigns (Rice and Atkin, 2001; Hornick, 2002; Siegel and Lotenberg, 2004). Yet interactive channels such as computers and mobile phones bring new issues to the fore and may not be adequately addressed by established social marketing paradigms (Lefebvre and Flora, 1988). Thus, the closest volumes available now are from the internet space (Rice and Katz, 2001) and from the mobile field (Fogg and Eckles, 2007; Fogg and Adler, 2009). The latter is an excellent, accessible volume by leaders in the field. However – similar to much of the literature available on mHealth – Fogg and Alder do not focus on developing countries, nor do they directly interrogate what works and what does not work with an eye toward best practices Mechael, Batavia, Kaonga, Searle, Kwan, Fu, and Ossman (2010). Chapter two by Kwan, Mechael, and Kaonga in this volume aims to bridge this gap in the literature and pulls from existing sources as well as the work of contributing authors and other practitioners using mobile to promote healthier behaviors.

The mHealthy behaviors sessions

This work began in direct response to the ample programming, increasing hype, and recognizable gap within the mHealth literature of what works and how it works when it comes to programs that aim to leverage mobile technology to engage individuals in stopping an unhealthy behavior or taking up an activity that would preserve their well-being and prevent the onset of illness and disease. With rapid increases in funding for such programs, particularly in low and middle income countries – where the health disparities are greatest – the need to unlock the secrets to the pathways to change became increasingly apparent. To start, we began by combing the literature and mHealth community for projects and research that could tell the mobile-mediated behavior change story from multiple angles – particularly from the perspective of those of practitioners implementing such programs and researchers evaluating their impact. We also wanted to address the ‘do-know’ gap in mHealth, whereby the majority of programs are being implemented in low and middle income countries with the majority of research and evaluation coming from high-income settings (Mechael and Searle, 2010). We also wanted to ensure geographic representation to compare and contrast the maturity of mHealth, cultural, language, and socio-economic considerations. It was through these lenses that authors and their respective projects and research were selected and invited to participate in what would become a nine-month long reflective exercise, which ultimately led to the full development of the chapters included in this book.

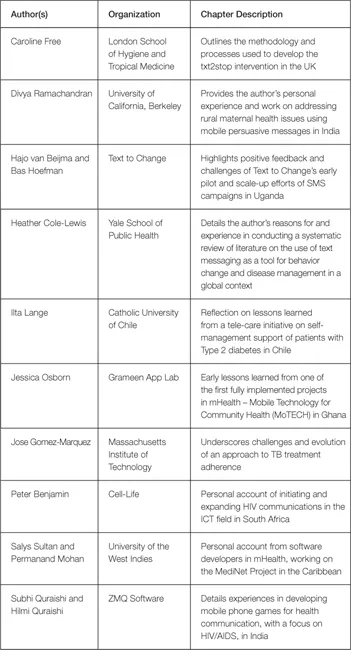

The projects and authors involved in this effort are as follows:

Table 1.1 Authors and subjects

While we specifically targeted this effort to focus on the use of mobile technologies for behavior change in developing countries, we included the work of Free at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine as the use of text messaging is increasingly being incorporated in smoking cessation campaigns throughout the world. The rigorous intervention design and research provides an excellent case study of what mHealth for behavior change initiatives ought to aspire toward as many now seek to transition from pilots to scale.

To begin this process, we invited each author to develop an abstract and/or short outline that addressed the following (deceptively simple) question: what is it that you intended to do, and why/how did you believe it would work? Related questions for authors included:

- Did/does your project have a specific model of behavior change? If so, how did you match your design to this model?

- Where did you go for guidance? What literature or other projects were influential? Is your model unique to ‘mobile’ behavior change or does it draw on/inform broader behavior change models?

- Conversely, how did the project execution inform your model? How did it evolve over time? Did you make any mid-course adjustments? Would you use the model again?

- How was your change model reflected in your evaluation plans?

- What methods did you use to assess the success of your program? To what extent were you able to measure changes in behavior?

- What recommendations might you make to program implementers and evaluators based on your experience?

The back-to-back workshop and roundtable included a discussion on the need for practitioners to engage both with formal behavior change theory and with the more iterative, natural pursuit of technological and organizational best practices, a gap that many in the medical (Lomas, 2007), education Amabile, Patterson, Mueller, Wojcik, Odomirok, Marsh, and Kramer (2001), and management (Amabile, Patterson, Mueller et al., 2001) communities have argued can be hard to bridge. It involved a ‘reflective spirit’ of interactive discussion (Schön, 1983; Argyris, Putnam and Smith, 1985) with elements of action research, a focus on guided discussion, open exchange, and reflection. Pre-work included reading excerpts of the Reflective Practitioner (Schön, 1983), and made references to the theatrical practice of ‘breaking frame’ (for example, Kantor and Hoffman, 1966) and to Failfare2, the set of ICT4D meetings in which failed projects are scrutinized, celebrated, and used as the basis for rapid learning. Returning to that deceptively simple question, part one (what is it you intended to do?) promised to bring us along well-trod paths in workshop settings, while part two (why did you believe it would work?) offered more opportunities for reflection, and more explicit links to change models (Frumkin, 2006). Many of the change models utilized by the contributing authors were done without prior or formal articulation; only a few had proactively researched and applied explicit strategies for behavioral change.

The half-day workshop was open to attendees at ICTD2010, hosted at the Royal Holloway campus of the University of London. Eleven invited panelists from around the world shared their experiences in a format that actively engaged the audience, including other mHealth practitioners and researchers, in the discussions. The sessions followed a ‘fish-bowl’ design; audience participants moved in and out of the discussion by taking a seat among the panelists. This session enabled us to gain a sense of the interest levels in the broader ICTD community, as well as to identify questions that we ought to consider ensuring that we tackle within this volume. Notes from this session are available on the public website for this reflective writing collaboration3.

The second session was a full-day, closed-door roundtable at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (also a part of the University of London). In preparation of the closed session, we provided targeted feedback to each of the authors to expand their abstracts to 3,500 – 6,000 word documents. The bulk of the roundtable was spent walking through change models and the application of theoretical frameworks to the various projects and research and discussing the paper drafts from participants. Practitioners and researchers in the mHealth domain were asked to approach their practice from a variety of perspectives, mixing formal or implicit theory (of behavior change, in this case), with intuition and adjustment on the fly. Numerous commentators have defined such approaches as ‘change models’.

mHealthy behavioral themes

This introductory chapter highlights many of the themes that emerged throughout the process of developing this edited volume and draws heavily on the public and private dialogue of the author...