CHAPTER 1

IN THE BEGINNING

‘We hold signs, take to the streets and pull fire from our throats … in the hope that we keep breathing long enough to see our grandchildren scream only in laughter, and not in protest.’

One day years from now, in a history lesson, a classroom of children will be asked to create a poster that they think accurately captures the events of 2020. If each student does not find their yellow, red and orange markers, and begin sketching a huge flame across a blank piece of paper … I will know that, once again, the textbooks have lied. A match was lit against the spine of 2020 and we watched our great plans for the new year flicker under a smoky sky. By March it seemed like the world had caught fire. We watched from our living rooms as the skies were emptied of planes, the earth had space to exhale, and colour and class raged against each other as if it were the sixties. Some of us thanked the higher powers that a global pandemic had chained us to our houses and made the decision for us to sit this race war out. Many people wanted to turn face masks into muzzles, mark their doors and keep their heads down, hoping that both the Black Lives Matter movement and COVID-19 would pass them by. But something was different this time. A mirror had been held up to the face of the earth and the open wounds that turned smiles into tears had never been more apparent. Especially when those tears became blood spilt from black eyes.

Extra melanin has meant extreme mistreatment for longer than I’ve been alive. We could be talking about the caste system in India that favours lighter skin while quite literally killing those with darker skin. We could be talking about the Arab media that only celebrates pale tones, or the film roles of the slave, prostitute, villain or thug, which are exclusive to darker brown skin. We could even be talking about the millions of children’s doll collections that are created everyday, each with white skin, rosy lips, long straight hair and European facial features. The world is wrapped in favouritism towards whiter skin, whether we care to admit it or not.

And despite global efforts to address this post-colonial pandemic, we have all built our lives and minds around this reality. This is particularly true for the police departments that are paid to protect the land. Somewhere in the DNA of the police officer, it seems an active wire of racism snaps and goes wild within them when faced with the opportunity to either serve a harmless black person their rights or kill them. The statistics are not pretty. In fact, they are truly terrifying. According to Statista, as of August 2020, for every one million US citizens, thirty-one unarmed black citizens are shot and killed by the police – the highest rate for any ethnicity. To know that my last breath lies in the hands of a volatile and highly emotional human being who feels justified in both discriminating against me and murdering me … it’s a very disheartening hand to have been dealt along with my mother’s black skin.

Perhaps you come to find this letter at a time when race is only celebrated, and not used to determine whether a person lives or dies. Perhaps you struggle to believe that humans could ever kill other humans because they look different to them. Perhaps your heart has evolved to the point that my heart, and millions of other tired hearts, reached centuries ago. So maybe this seems far-fetched to you. If you’re reading this even ten years from today, I really hope it does. I hope you’re filled with disgust, doubt and curiosity. But in the likely event that the textbooks and the statistics change, and the essays are lost, and the artists get tired of the truth, and the news moves on and the silver lining becomes the entire picture of 2020, here’s the truth of today …

Black people are still getting killed for being black. The killers sometimes become celebrities. In the case of George Zimmerman, who fatally shot unarmed, innocent seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin in 2012, the killer becomes a hero, who has rid the street of another black future. Zimmerman went on to try to sue the family of Trayvon Martin, appear on news shows and begin a new career as a glorified killer. There was something about this particular killing, amid the many that took place that year, that split the ground beneath us. Before the blood had dried, the potency of witnessing the loss of a son and unarmed teenager, a grieving mother, a not-guilty verdict and an acquitted killer unearthed a twentieth-century rage that seemed to come from the belly of the civil rights movement. A video recording was released proving the innocence of Trayvon Martin and his cold-blooded killing by George Zimmerman. Yet somehow, a jury found him not guilty. Somehow, a video of the events was just not enough. Somehow, the law was put aside and Trayvon Martin’s parents had to watch their son’s killer become a celebrity. The right side of the world shook with rage. With helplessness. With confusion. Then we shook into formation. The Black Lives Matter movement was created by Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi as a response to the staggering number of innocent black deaths across the world. Unfortunately, all of the press, all of the support and all of the evidence since just hasn’t been enough to stop the same thing from happening over and over and over again. It’s tiring. And, if I’m completely honest with you, on the day of this protest that changed the world (hopefully for good), I was actually too tired of this vicious cycle to even leave my house. Had it not been for the mandem, perhaps you wouldn’t be reading this letter. Here is what has led me, so led you, to this letter. An afternoon in London that completely transformed my life.

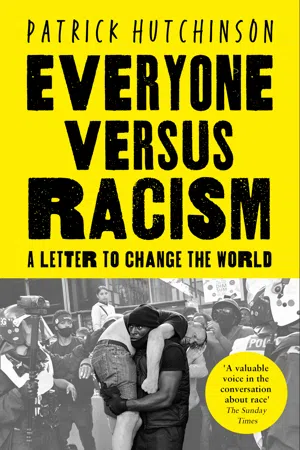

On the thirteenth day of the sixth month of an already very devastating year, we changed the world. Hopefully. Unintentionally. I didn’t plan to. In fact, my own plan for that Saturday afternoon was to play with my two grandchildren, do some exercise and pray that the day’s protest didn’t go as horribly as many of us envisioned it would. We were at war again. They had killed another innocent black man. A video had gone viral of a police officer named Derek Chauvin pressing his knee onto the neck of George Floyd on the side of a road in Minneapolis, Minnesota, suffocating him without restraint, with his hands in his pockets, until George Floyd could no longer breathe and was killed. Passers-by screamed and watched. Other officers watched and filmed. Derek Chauvin looked into the lens of the camera and kept his knee on George Floyd’s neck for over eight minutes. Even those who somehow found an excuse for every police killing could not excuse this graphic murder of George Floyd. A father, son and friend to many. Due to a medical pandemic that had everyone strapped to their sofas, working from home and being online more than ever before, the video went viral very quickly and demanded the attention of just about everyone with a heart. For some, this was their first sight of how blatant racism could be. For many of us, though, we were hurt but not shocked. As a black man who’s grown up in a predominantly white London, I’ve known how vicious racism can be from a very young age. That’s why my friend called me on that Saturday morning, begging me to attend what was meant to be a peaceful BLM protest, had it not been for the propaganda that Tommy Robinson had infected the air with.

The overtly racist and hugely problematic EDL party leader Tommy Robinson released a video encouraging football hooligans, thugs and anti-black people to disrupt the peaceful Black Lives Matter protest. The video made me sick to my stomach. Not because of the hate speech. Or the blatant and unsubtle agenda to silence a movement that finally seemed to be impacting on those who needed to bring about change. But because of what it exposed about how part of Britain’s heart feels towards black people’s survival. My gut twisted itself into a fist of rage. And while I’m a trained martial artist who knows how to channel that anger with wisdom without inviting arrest (not that you have to do much as a black man), this isn’t the case for many of us. And I get it. How dare this white man unleash his dogs on our protest? How dare he trigger our people at a time such as this? The blood is still wet. For many people, deciding not to protest would be feeding their oppression. And so the hundreds that still came out that day and screamed louder and marched harder, they refused to let a white man win. My friend had watched the video of Tommy Robinson and knew this was bad news. He empathised with the black protesters who would still leave their houses that morning and face the racists head on. My friend was well aware of how dangerous rage could be once it is reciprocated. It wasn’t a fate he wanted for anybody. Least of all vulnerable black people.

When he called me that morning, I asked why he felt we needed to do this. He’s a spiritual man and he said he had felt nudged by his ancestors to put his career in security to good use in this way. To go out there and protect those who needed protecting, since we all knew the police had no intention of doing so. This completely resonated with me.

Between the six of us guys who ended up heading out to the protest that Saturday afternoon, two of us worked in security and all of us were trained in martial arts. Defence was what we were built for. Protection was more than a job. It was our duty as able-bodied, well-trained black men to step into ourselves on that day. Yes, however, was not my first response. In fact, it was quite the opposite. I’m sure I started by saying no. Not because I didn’t think we needed to do this, but because I had my grandchildren nestled in between my bicep and forearm, and anybody who has held a baby knows how impossible it is to leave them once those little angels have found comfort in your presence. Like my mother before me, I feel entirely obligated to my role as a protector of these cubs. I didn’t grow up with a father present. In fact, thanks to him, I spent years assuming I had no older men in my life at all beyond my uncle and his friends – only to find that this wasn’t the case. But that’s a story for another letter. Maybe this was what would get me off the sofa and take me into my room to find a face mask and some gloves. Perhaps it was the desire that lives in any son who grew up without a dad that forced me to find my feet and be a better example of leadership. Or maybe it was seeing how safe and blissful my grandchildren were when they were around me. Perhaps something of that security reminded me of how safe I felt as a twelve-year-old when I spent time with my uncle Charles and his friends. I felt brave when I was with them. Like nobody could disrespect us. I was proud of my blackness and loved being one of many. It’s a real shame to then learn when you grow up that even though I felt so warm in the centre of blackness, to onlookers we were an immediate threat. I became sure that those who did feel threatened by collective blackness were probably the same people who would turn up to antagonise the protesters. Why did they hate us this much? We weren’t even protesting for equality. Simply just to matter, and not be killed.

My friend and I exchanged a heavy silence on the phone. I could feel how sure he was that we needed to be there. His spirit man had already seen the number of lives we would save that day, and who am I to argue with his God? I looked down at my grandchildren and my heart tightened. Perhaps if I went out to protect the Black Lives Matter image today, they wouldn’t have to march tomorrow for the exact same, tired reasons. Maybe in protecting the mothers and children in the streets today, I was protecting these adorable black seeds of mine. Maybe by putting them down today, I was actually lifting them up for tomorrow. Quite quickly, my maybes became definitelys and I kissed the little angels on their precious foreheads and stretched my fatherly heart around London. After all, everyone deserves someone who’s dedicated to protecting them. And if the police won’t, the people should. Well … at least the trained, strong, present-minded people should. That’s what my friend thought, anyway. I wasn’t the first person he called who said no. Some of the guys he tried refused to play the role of policemen after all that the force had put our people through. Some were tired of having to be the good guys all the time and others genuinely feared that this was a deadly set-up. But the six of us who went to the protest that day weren’t thinking about our own lives. At least, not in a fearful sense.

As we made our way towards the protest, we were confident in our skills and our ability to defuse situations and protect the vulnerable. My friend, Jamaine, Sean and I drove past Parkway and parked in Vauxhall. My friend and I in one car, Jamaine and Sean in the other. We met Lee and Chris at Vauxhall Station. I’m familiar with the area, so I knew where we could park without getting a fine or our wing mirrors knocked off. Walking across the bridge from Vauxhall, we saw the first signs of what we were heading into. There were smaller groups of EDL men standing around. They were looking at us and we were looking at them. We all knew exactly what it was between us. We knew why they had come out to disrupt a Black Lives Matter protest, and I guess they assumed we’d come to stop them. The air thickened, our throats tightened and we shared a long, deep exhale as we headed towards Parliament Square. The day resembled a carnival in some ways. It felt like we were walking for ages and some of the boys went off on their own to see what was happening, and where it was happening. Once we had all come back together, we ended up back at Vauxhall and thought it best to get on a train towards Piccadilly. As four or five of us climbed into the carriage, it was as if the world paused for a moment. There were EDL anti-black protesters and football hooligans already taking up space on the train. They looked at us in a funny way. My friend Jamaine described it as how an animal looks at its prey while it’s waiting for the perfect time to attack. There was a strong sense of ‘not here, but later’ oozing from the stares and whispers of the white men.

After all the convincing that my friend had had to do, we were actually a bit late to the protest, ironically feeding the stereotype of black men’s poor timing. But in our defence, in that short window of time we’d had to find sitters for our children and protective outfits to change into. We got to the square at around 2.30 p.m., and by this point there were roadblocks and redirections everywhere. Police officers kept telling us to go this way or that way, or that the path ahead was blocked. We made a point of remaining polite when talking to the police, aware of our huge physiques and dark skin. Thankfully the police made a point of doing the same. If only this were the norm. Better yet, if only we didn’t have to consider how to act innocent, without ever having committed a crime. As we walked towards Trafalgar Square, we passed smaller groups of anti-black protesters who always made a point of nodding their heads at us or breaking the tension with a ‘You good, bruv?’ The greeting became an attempt at a white flag. Perhaps to say that they weren’t trying to antagonise us. On a normal day I’d enjoy nodding back and returning it. But today, despite how desperate a white man might be to break the tension, I couldn’t shake the fact that he’d come here on Saturday on the thirteenth day of the sixth month, for a reason that I really struggle to digest.

(© TKE)

By the time we got to Trafalgar Square, our six had become five. One of our boys was tired of walking, and I didn’t blame him. I had to keep reminding myself why we had come, and why it was worth leaving my grandchildren. Although London that Saturday did not let us forget why we came. As we got closer and closer to the body of the march, on every corner we turned there was a new group of football hooligans or white thugs throwing bottles at the police or chanting racist slurs into a wind that was meant to carry the voice of peaceful black protest. With each step into this dark, twisted moment, it became terrifyingly clear that the anti-Black Lives Matter protesters wanted violence. They were itching for the opportunity to crack open their bodies and launch their prejudices into the spirit of London. They wanted to see the black man snap and they wanted the media to see it, too.

From behind a wall of police, a mob of white men screamed non-rhythmic chants and slurs towards a sea of black people who were waiting patiently for them to finish so that they could continue to fight for their right to survive. This really wasn’t what the Black Lives Matter protesters needed that day, while innocent people were being killed on camera at the hands of police across the world. The mob screamed everything from ‘We are racist, yes we are’ to ‘Black lives don’t matter’. They stretched their hateful necks above the police, who protected them from the consequences that were naturally brewing in the bellies of the BLM protesters. And they screamed. They broke the wall of silence that tends to protect the ignorant opinions of those who are adamant that racism doesn’t exist. They screamed louder than that denial. They screamed and woke Britain up to its racist side. They screamed in the hope that if one of those screams could pierce through enough black ears, a riot would occur. And if they could get the black people to the point of fighting, the media would quickly remember only the violence that came from the protests. Oh, the luxury of knowing one’s privilege.

At the square we bumped into quite a few people we knew. Stories from the day poured from their lips, and we pieced together a picture of the protest so far. As they told us of the smaller fights that kept breaking out like little fires across London, the square began to de-mist and became a showreel of the things they were saying. They became narrators of a scene in which we had all become actors. That’s what it felt like. A movie. Usually, when racism is this destructive, it is subtle. It’s in the micro-aggressions in the workplace or the inaccurate school curriculum. Today it shone with the sun and burnt any doubt I may have had off of my back. The racism was raw. Loud. Undeniable. From any angle, you could see smaller squabbles breaking out between drunk white football hooligans and the Black Lives Matter protesters. It was beginning to look like a ticking time bomb, and the police knew this, too. We all knew that at any given moment, a full-blown brawl could commence. Most of the Black Lives Matter protesters had never been in a brawl before, nor had they left the house that morning with any intention of fighting. The same could not be said for everyone. The jaws of the anti-black thugs gnashed like fighter dogs waiting to be unleashed. The police knew that if they did not bring this protest to a close, and quickly, anarchy would break out.

Around 5 p.m. they began to usher us all towards Waterloo Bridge. As everyone walked over the river, I’m sure some very dark thoughts crossed the minds of some of the anti-Black Lives Matter protesters as they funnelled down towards the station and the Southbank Centre. Between us guys, we had said that as long as we stayed vigilant and remained together, we would be okay. Although our initial aim was to protect the vulnerable Black Lives Matter protesters, we quickly realised that the right thing to do was protect anyone who was in harm’s way. This included several anti-black disrupters. The point of all these protests was to make it clear that somebody’s skin colour should not be the defining factor in whether they live or die. How, then, could we ignore it when a white man was left on his own to finish a fight that he might have started but would certainly lose, and possibly die from, if the situation was not defused? My natural instinct is to protect the vulnerable. When we saw a car carrying EDL thugs get stopped and sat on, we knew that if we didn’t help them go home (and hopefully rethink their prejudice), they could become victims of the very abuse they had come out to serve. So we pulled people of all colours from the sides of the car...