1

Unions, Youth, and the Cold War

Conflict between the transwar generation of union leaders and young workers in the 1960s had its roots in the twin pillars of the mass-mobilization strategies developed at the end of the Allied Occupation (1945–52). Leaders of the Nihon Rōdō Kumiai Sōhyōgikai (General Council of Trade Unions, or Sōhyō) committed the rank and file to a collective bargaining strategy aimed at raising the wages of male-headed households and a “peace” platform of unarmed neutrality in the Cold War. The class-based gender-role ideals of the family wage advocated by the first wave of postwar labor leaders—all men active in leftist politics during the 1920s and 1930s—forged socially conservative ideas about “work,” “womanhood,” and “manhood” that would define leftist politics well into the 1970s. High economic growth dramatically raised unionized blue-collar workers’ wages and aspirations, such that by the 1970s blue-collar workers—young and old—increasingly dreamed of living a middle-class lifestyle. However, Sōhyō’s collective bargaining strategy also marginalized female workers and stratified male workers’ wages along generational lines, producing a generational schism in the 1960s. Politically, blue-collar youth shared the transwar leadership’s opposition to the US-Japan Security Treaty. However, in the global context of rising anti–Vietnam War sentiment and ethnonationalists’ demands for the reunification of Okinawa, a distinct minority of radical youth rejected the mass nonviolent tactics of their parents’ generation in favor of political violence.

This chapter investigates how Left-led unions nevertheless failed to create political propaganda that was persuasive to youth born after 1945; instead, they continued to promote an idealized working-class home using the tools they developed from their experience of the interwar and wartime eras. The sophistication of their visual propaganda is a reminder of the fact that Japanese of all classes were impressively literate and had access to a wide array of posters, newsletters, newspapers, and magazines. This chapter traces how the propaganda portrayed classed notions of manhood and womanhood that, by the 1960s, represented policies that did little for the young blue-collar men and women whose interests were different from those of the previous generation. It further shows how the visual propaganda deployed by leftist unions framed the failure of Japan’s socialist labor movement in order to sustain its youngest members’ levels of commitment.

Leftist Visual Propaganda

Reading the labor movement’s visual propaganda presents an interesting challenge. The posters, handbills, pamphlets, and political cartoons of that period incorporate a highly politicized visual field that is entwined with rhetorical polemics printed in logographic characters, with historical as well as semantic meaning. Amid the political milieu of the 1950s and 1960s, union activists, writers, and cartoonists found socially conservative gender roles more suitable for mobilizing the movement’s members against the security treaty, in part because the treaty resonated with their own expectations that men worked for wages and women took care of the home. Since the 1920s, visual propaganda had featured prominently in the political campaigns sponsored by Left-led labor unions. Spanning from the rise of militarism and authoritarianism in imperial Japan to the cultural and political milieu at the center of Japan’s postwar democracy, these visual sources open a unique window onto the domestic conflict and turbulence that fashioned twentieth-century Japan. The broad basis of literacy evidenced in them can be traced back to the educational reforms introduced in the latter half of the nineteenth century, which included both blue-collar workers and farmers. Consequently, leftist parties and labor-farmer associations generally churned out a variety of posters, newsletters, newspapers, and magazines to inform and inspire their supporters.1

A simultaneous phenomenon of the modern era was the rise of a new, politically conscious urban intelligentsia who were deeply engaged in publishing original leftist articles and books, and translating many of the fundamental Marxist, socialist, and Communist texts that defined radical thought in the Western tradition in formats that could reach a diverse audience, including the urban proletariat as well as farmers, foresters, and fishermen. Marx, Lenin, and a great many other radical theorists and polemicists became accessible not just through the printed word but also through a variety of visual propaganda produced specifically to reach an audience that was keen to correct existing injustices inherited from the past. Most periodicals associated with leftist parties and unions were short lived: government censorship and repression, coupled with organizational infighting, did them in. Nonetheless, some survived long enough to have an impact. Additionally, they were buttressed by another genre of radical protest: proletarian literature. In the postwar era, this genre came to include a very sophisticated corpus of political cartooning.

Ironically, the seven years of Allied occupation gave the labor movement time to reorganize and grow. The wartime state forced many leftists to recant, and those that refused were put into prison, or worse. A sizable number of the cadre who survived the war with their leftist ideological vision intact reemerged after 1945 to continue their role as the avant-garde of leftist culture. John Dower and Miriam Silverberg have detailed the extent to which many immersed themselves in the hedonistic, erotic/grotesque (eroguro) culture that took advantage of Japan’s American interregnum to reject the statist cultural mores that had dictated the political and cultural environments within which they had lived and worked prior to 1945.2 The visual propaganda they produced—political ephemera that included magazine art, cartoons, film posters, and political pamphlets and handbills—offers a fascinating window into the goals, purposes, and consequences of the political struggles in which Japan’s largest social movements were engaged. While organized labor’s postwar political agenda went mostly unrealized, the efforts of the many individual activists who were involved set significant precedents for autonomous patterns of change, resistance, and accommodation, which continue to reverberate within the political framework of contemporary Japan.

Japan’s Left-led unions worked in close collaboration with sympathetic artists and intellectuals to create what they hoped would become the basis of socialist national culture in Japan. The aim of the postwar collaborations between leftist artists and union activists was to churn out labor-friendly publications, essays, and speeches. Established in 1954, the National Congress of Culture (Kokumin Bunka Kaigi, or NCC) received the bulk of its funding and logistical support from Sōhyō. For the next three and a half decades, Sōhyō leaders encouraged union activists to call on the small staff of the Tokyo-based NCC whenever they needed an article or speech for a publication or event. Official sponsorship, as well as a stable funding base, enabled the NCC to become the central cultural agent for the Left-led labor movement. In return, the NCC provided much-needed funding and political support for scholars, writers, and activists, who themselves belonged to, or headed up, a wide range of left-leaning cultural associations, citizens’ activist groups, and think tanks. By the mid-1950s, the NCC had grown into the preeminent “culture broker” for organizations affiliated with the Left-led labor movement, and it acted as the hub for a vast network of artists and intellectuals who were engaged in producing cultural material for an emerging socialist subjectivity among Japan’s working class.3

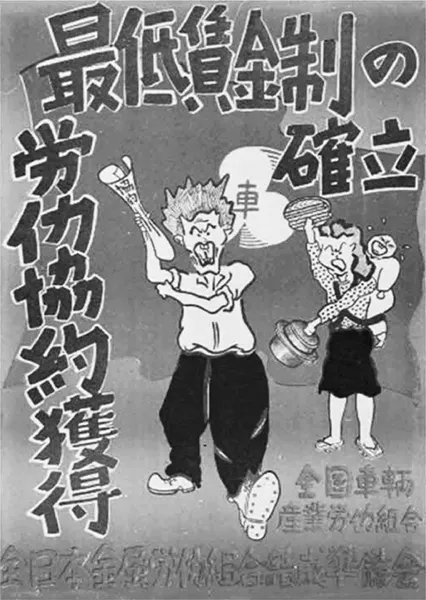

The actual impact of visual propaganda is nigh impossible to determine, but a close reading of extant examples does provide an excellent window into the general mentalité of the era. The notion of a male-centered family-wage ideal was already operative in many unions. The poster reproduced in figure 1.1, which was printed for a 1948 strike by the steel and rolling stock workers’ union, portrays a male worker with his sleeves rolled up to his elbows; he is brandishing his contract while stridently demanding a guaranteed minimum wage. In the background and to his left stands a woman, most likely representing his spouse, who is brandishing a rice cooker and has an infant on her back. She is echoing his demands for a wage sufficient to support a wife and child at home. Armed with gendered and classed rhetoric, leftist labor unions papered the streets and alleyways of postwar Japan with visual propaganda calling for the Japanese proletariat to resist the reemergence of totalitarianism and the US-Japan Security Treaty. While the Left-led labor movement in Japan was not intrinsically anti-American, the Allied Occupation government became increasingly hostile toward Japanese labor. By the summer of 1948, US officials perceived the labor movement as a Communist insurgency in occupied Japan. The ironic consequence of this shift in occupation policy for organized labor was that the American-dominated Allied Occupation government’s anti-Communist machinations led to the formation of Sōhyō, and its dominant position representing the public-sector labor force empowered Left-socialist labor leaders who, by the mid-1950s, were calling for the eviction of US military forces from Japan.

The Cold War also greatly influenced the political propaganda produced by Japan’s Left-led labor unions. Nearly a month before the outbreak of hostilities in Korea, and on the third anniversary of Japan’s postwar constitution, the supreme commander for the Allied powers, Major General Douglas MacArthur, declared that he doubted that the Japan Communist Party (JCP) deserved equal protection under the new constitution. MacArthur used a relatively minor incident as an excuse to order Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru to purge the JCP’s top executives, as well as more than twenty thousand dedicated JCP activists. With the outbreak of war on the Korean Peninsula in June 1951, MacArthur suspended the publication of the JCP newspaper Akahata (Red flag), disbanded the JCP-friendly labor confederation Zenrōren, and actively pressured private employers to purge Communists from their firms.4

As the Cold War unfolded in East Asia it radically altered the political landscape of occupied Japan and precipitated American public sentiment that the United States’ global position was beginning to unravel. Ironically, Douglas MacArthur’s preemptive purge of labor militants in 1949 precipitated the crisis he said he wanted to avoid. Takano Minoru, the founding secretary general of Sōhyō, advocated for Japan to join the emerging nonaligned nations movement as a means to abstain from allying with either of the two superpowers. The United States’ foreign policy advisers decried the Non-Aligned Movement—led by Jawaharlal Nehru, Gamal Nasser, and Sukarno—as a Soviet Union ploy to undermine US interests in the developing world. Nevertheless, in the weekly newspaper published by Japan’s largest labor federation, Takano asserted that the war in Korea was evidence of an encroaching US military hegemony in East Asia and that the critical role that US military bases in Japan played in servicing the war flew in the face of the struggle for decolonization and self-determination shared by all East Asians.

Figure 1.1 Union propaganda of the 1950s relied on an iconography of the ideal working-class man and woman, in which men were represented as militant wage earners fighting to protect their jobs and women were militantly fighting to protect the family and home. The All-Japan Rolling Stock Workers’ Union and the All-Japan Steel Workers’ Union, 1948, 37 cm x 53 cm, O¯hara Digital Archive: PB0102. Reprinted with permission of the O¯hara Institute for Social Research at Ho¯sei University.

President Harry S. Truman’s decision to dismiss MacArthur and end the Allied Occupation further encouraged Takano to renew union mobilization against what he asserted were American imperialist ambitions in East Asia. Posters promoting the 1952 May Day rally marked both the annual labor celebration and the end of the Allied Occupation of Japan, which had ended two days prior to the federation’s planned May Day celebration. The slogans on the poster depicted in figure 1.2 call for Japanese workers to oppose rearmament and protect the 1947 constitution. Produced in line with Takano’s official call to assert Japan’s national autonomy through the promotion of intra-Asian unity, the poster features two masculine hands grasped in an intraregional handshake extended between China and Japan; the Korean Peninsula lies in the middle. The poster calls on all Japanese to defend the 1947 constitution of Japan, known colloquially as the “Peace Constitution,” by opposing MacArthur’s 1951 directives to rearm Japan, which many Japanese perceived to contradict Article 9 of the postwar constitution. The poster’s rhetorical purpose was to communicate Sōhyō’s anti-imperialist message amid Japan’s newly reacquired national sovereignty. However, there is an implicit gender ideal in its focus on strong, masculine hands joining in regional solidarity, which is further reinforced by an iconography of womanhood that portrayed Japanese women as housewives struggling for peace in solidarity with their husbands’ unions.5

In the spring of 1952, Sōhyō and its affiliated unions declared their support for the idea that “the right of self-governance is in the hands of skilled workers,” and called for an intraregional workers’ alliance, an end to the Yoshida government, and the establishment of diplomatic relations with China and North Korea. They advocated that the return of Japan’s national sovereignty empowered Japanese workers to determine their relationship with their brothers in China, Korea, and even Southeast Asia, all of whom shared a common ideological framework and ethnic-national heritage. While this particular political vision was never realized, Sōhyō did send representatives to the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union throughout the 1950s and 1960s, w...