Chapter 1

Setting the Stage

The Javanization of Colonial Authority in the Nineteenth Century

In January of 1900, Raden Adjeng Kartini, a vocal Indonesian advocate for women’s rights, wrote an elaborate response to Stella Zeehandelaar, a Dutch friend who questioned whether the general “condition” of the Javanese people had improved since the abolition of the Cultivation System. The repressive forced cultivation of cash crops had characterized colonial Indonesia from 1830 to 1870. Kartini replied that while there were many indications that the government now cared for the welfare of the Javanese, colonial officials, who acted as Javanese aristocrats, maintained their sense of superiority. As an example, Kartini related the experience of a young Indonesian man who attended a European high school and graduated first in his class. At school, he was accustomed to conversing in Dutch and interacting freely with Europeans. On returning to his parents’ hometown to join the colonial civil service, he therefore assumed that he could address the local resident (colonial administrator) in Dutch. This was a crucial mistake, Kartini wrote, as the next morning he was assigned the position of clerk to a lowly European official in a mountain town. To make matters worse, his Dutch superior was eventually replaced by one of the man’s former classmates—a European of inferior intellectual capacity for whom he had to crouch, sit on the floor, and address solely in high Javanese. According to Kartini, the young official learned a life lesson in Java’s mountains: the best way to serve European officials was by groveling in the dust and never speaking Dutch. For good measure, Kartini offered several additional examples of Dutch mimicry of the Javanese elite, such as demanding to be addressed as “great lord” (kanjeng), to receive a knee kiss (sungkem), and the right to walk under a gilded parasol (payung). She sarcastically added that she had always thought only the “backward Javanese” loved all this pomp and circumstance but learned that “civilized and educated” Westerners craved it, as well.1

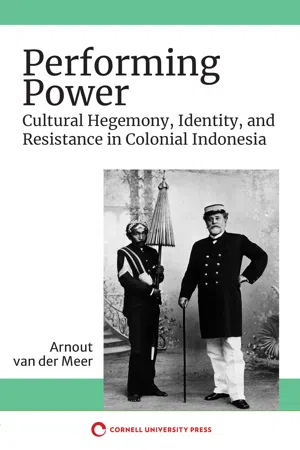

Kartini sketches an intriguing portrait of the late-nineteenth-century Dutch performance of colonial authority. Although her letter conveys that the colonial appropriation of Javanese forms of etiquette and deference was adopted during the Cultivation System, the Dutch had been experimenting with employing local rituals and symbolism as a means of regulating contact between colonizer and colonized for much longer. This approach can be traced back to the seventeenth century, when the Dutch East India Company (VOC) first established a permanent presence in Java. However, Kartini was correct in that it was during the nineteenth century that the Javanization of colonial authority was institutionalized and made into a pillar of colonial rule.2 This was not a straightforward process, but it was a deliberate policy of cultural appropriation through which the Dutch tried to communicate and justify their dominance in recognizable terms. The Dutch thus created hegemonic standards of public conduct that provided at least the outward impression of conformity to racial and social hierarchies and helped reify difference in colonial society. This chapter explores in detail the conscious development of a Javanized colonial performance, encapsulated in meticulous regulations regarding etiquette, dress, status symbols, architecture, and even culinary culture, and acted out according to a hegemonic script. Crucially, the Dutch were more than the directors of this colonial performance; they played the leading roles.

The Javanization of the performance of colonial authority has received scant attention in the historiography of colonial Indonesia. Most studies dealing with nineteenth-century Java have focused on the political economy, primarily the material exploitation of the Javanese, and discourses justifying colonialism, including analyses of race and gender. In these studies, cultural appropriation is often considered a byproduct of these other aspects of colonialism.3 What has been published on culture and power is often limited to specific cultural elements in isolation, such as dress, rather than as significant parts of a larger system of cultural domination.4 This is a missed opportunity, as hegemonic discourse was communicated through everyday cultural performances to rationalize colonial inequality and exploitation. It is therefore necessary to consider the regulation of etiquette, classificatory schemes, rituals, and the appearance of power as integral components of the system of colonial governance. Doing so offers a cultural layer to scholarship about the institution of indirect rule, its reliance on a dualistic civil service, the comprehensive system of racial stratification, and the politics of sex.5

The Dutch East India Company:

Profitability and Cultural Exchange

The Dutch East India Company established a foothold on the northwest coast of Java in an attempt to control the seventeenth-century spice trade. In 1619, the VOC destroyed the town of Jayakarta and constructed Batavia (present-day Jakarta) on its ruins, creating the center of its Asian maritime trade empire. While the company had operated trading posts in Java since 1603, it was establishing Batavia that marked the Dutch’s permanent presence on the island, thus requiring the formulation of settlement and colonization policies. As the first multinational corporation in world history, these policies were informed by cost efficiency and profit maximization but had significant effects on the intricacies of Dutch colonial culture in Java for centuries. In a way, it was the VOC’s obsession with the bottom line that created the circumstances out of which colonial officials in Kartini’s time emerged.6

In order to transform Batavia into a dominant center of intra-Asian trade, the VOC sought to create a stable settlement population as the basis of its strength. Rather than relying on settler colonialism (unlikely in a densely populated area resistant to European diseases—instead Europeans were at risk of tropical diseases), the company enforced strict regulations on immigration and conjugal relations. Only high-ranking officials were allowed to bring European wives to Batavia, while lower officials and company personnel were actively encouraged to cohabitate with or marry local women. As Jean Gelman Taylor meticulously shows, the Eurasian offspring from these unions quickly became the bedrock of Batavia’s social world, where they grew up in predominantly Asian households, conversed in Malay, consumed indigenous cuisine, and wore locally inspired clothing. Cultural exchanges in these Eurasian households further shaped gender relations, spiritual beliefs, deference behavior, hierarchical rituals, and material markers of social status. The VOC had intended that their settlement policies restrict private trading interests while at the same time create a small settler community to supply cheap Eurasian manpower for lower rank positions. But by the mid-seventeenth century, their regulations had also resulted in an autonomous colonial society with a culture that could no longer be characterized as either Dutch or Asian but as Eurasian. Through this particular colonial society, the Dutch gleaned valuable knowledge about local culture that would become instrumental for the Javanization of colonial authority in the nineteenth century.7

The Dutch East India Company initially had no intention of pursuing a land-based empire in Java, content with its settlement in Batavia and its status as a vassal of the largest kingdom on the island. However, to protect and expand its mercantile interests, the company was gradually drawn into internal Javanese politics. Between 1677 and 1749, the VOC increasingly gained sovereignty beyond Batavia by exploiting the indigenous kingdoms’ rivalries and internal weaknesses. This process culminated in 1755–57 with the division of the once-powerful sultanate of Mataram into three princely states, of which Surakarta and Yogyakarta were the largest and most important.8 Within a century, the VOC thus acquired control over most of the island save the newly formed principalities. On paper the Javanese rulers retained sovereignty over their much-reduced territories, although the company exercised significant influence at the princely courts through company representatives. The resulting situation left room for competing views on the relationship between the Dutch and the Javanese rulers.9

The VOC’s territorial expansion from its base in Batavia forced the trading company to consider how to rule its colonial possessions. Due to a preference for an indirect system of governance, also informed by economic concerns, the company’s administrative structure was predominantly Javanese in personnel, organization, and ideology. The VOC relied on collaborations with the Javanese bureaucratic elite, the priyayi, a social group consisting of nobility, officials, and administrators. In practice, this meant that the highest members of the priyayi, the traditional Javanese regency heads known as bupati, were allowed a large degree of independence as long as they remained loyal to the VOC, abstained from relations with foreign powers, guaranteed peace within their districts, and promptly collected and delivered the required tribute.10 Often their power even increased from their service to Javanese courts, since supporting the Dutch allowed them to transgress the norms of the indigenous social system.11 A noticeable exception to this rule was the administration of the Priangan, the mountainous region immediately south of Batavia, where in the latter decades of the eighteenth century the VOC made the bupati subservient to company officials in order to directly oversee the forced cultivation of coffee beans.12 This incorporation of bupati into the colonial administration of the Priangan provided the company, according to Heather Sutherland, with “the methods of establishing, maintaining, and legitimizing authority which had developed in Java over the centuries.”13

As they extended their control over Java, the Dutch acquainted themselves with the intricacies of a Javanese system of social and political organization. With origins in the Hindu-Buddhist period of the island’s history (between the eighth and fifteenth centuries), a distinctly Javanese political order developed, characterized by bureaucratization, social stratification, and a style of rulership inspired by Indic cosmology. An abstract concept of social hierarchy known as kawula-gusti (servant-master or patron-client) outlined the relationship between the king and his subjects, and also applied more generally to relationships between social superiors and inferiors. This hierarchy governed chains of patron-client clusters that extended from the royal courts to local officials and beyond. In theory, the kawula-gusti relationship was based on mutual respect and reciprocal responsibility through which the master protects and the servant pledges devotion in return. This vertical relationship was intricately expressed in sartorial etiquette, language hierarchies, demonstrations of social deference, status symbols, and cultural performances, such as wayang, a form of (shadow) puppet theatre, and gamelan, a traditional Javanese percussion ensemble.14 These forms of social communication were more than just trappings of power; they were theatrical rituals that, according to Clifford Geertz, “were not mere aesthetic embellishments, celebrations of a domination independently existing: they were the thing itself.”15 These theatrical displays of power would become essential to legitimizing and preserving Dutch colonial authority in Java.

The Dutch East India Company’s colonization policies—limited immigration, unions between European men and Asian women, and indirect rule—created a colonial society that was highly attuned to Javanese social and cultural traditions. By the late seventeenth century, Javanese status symbols and deference rituals were employed to differentiate between various social classes and ethno-religious groups living within Batavia, as well as between company officials and the Javanese priyayi who facilitated the system of indirect rule. The Dutch preoccupation with these Javanese manifestations of power even inspired the promulgation of various sumptuary laws and deference regulations. For instance, in 1719 it was decided that on encountering the governor general on the road, Europeans and Eurasians were required to dismount their horses or carriages and bow, whereas a Javanese was expected to squat on the spot as a gesture of deference. This squatting as well as the custom to approach a superior in a crouching-walk were known as jongkok and were an appropriation of customs previously reserved for Javanese royalty and aristocrats.16

One of the colonial Dutch’s more intriguing and popular adoptions was that of the Javanese payung, a ceremonial parasol that, through its colors, bore the distinctions of its owner’s rank. Most likely introduced in Java as a status symbol during the Hindu-Buddhist period, the payung was one of the most revered symbols among the Javanese aristocracy. A servant carried the payung while following the bearer of authority either on foot or in his carriage, or while sitting close to him on the ground.17 Both in precolonial and colonial Java, there were two elite hierarchies: that of the noble families who had the right to carry a payung from birth, and that of the Javanese priyayi who had the right to carry the payung by virtue of their office.

Europeans and Eurasians living under the auspices of the VOC were quick to adopt the payung as a status symbol. Its growing pop...