eBook - ePub

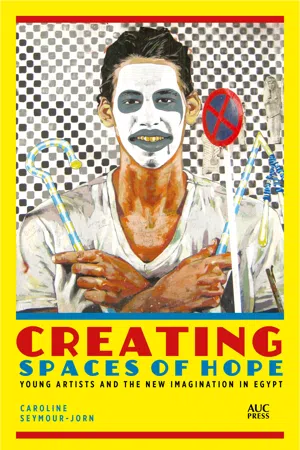

Creating Spaces of Hope

Young Artists and the New Imagination in Egypt

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

An exploration of how young artists imagine and maintain hope in post-revolutionary Egypt

Creating Spaces of Hope explores some of the newest, most dynamic creativity emerging from young artists in Egypt and the way in which these artists engage, contest, and struggle with the social and political landscape of post-revolutionary Egypt.

How have different types of artists—studio artists, graffiti artists, musicians and writers—responded personally and artistically to the various stages of political transformation in Egypt since the January 25 revolution? What has the political or social role of art been in these periods of transition and uncertainty? What are the aesthetic shifts and stylistic transformations present in the contemporary Egyptian art world?

Based on personal interviews with artists over many years of research in Cairo, Caroline Seymour-Jorn moves beyond current understandings of creative work primarily as a form of resistance or political commentary, providing a more nuanced analysis of creative production in the Arab world. She argues that in more recent years these young artists have turned their creative focus increasingly inward, to examine issues having to do with personal relationships, belonging and inclusion, and maintaining hope in harsh social, political and economic circumstances. She shows how Egyptian artists are constructing “spaces of hope” that emerge as their art or writing becomes a conduit for broader discussion of social, political, personal, and existential ideas, thereby forging alternative perspectives on Egyptian society, its place in the region and in the larger global context.

Creating Spaces of Hope explores some of the newest, most dynamic creativity emerging from young artists in Egypt and the way in which these artists engage, contest, and struggle with the social and political landscape of post-revolutionary Egypt.

How have different types of artists—studio artists, graffiti artists, musicians and writers—responded personally and artistically to the various stages of political transformation in Egypt since the January 25 revolution? What has the political or social role of art been in these periods of transition and uncertainty? What are the aesthetic shifts and stylistic transformations present in the contemporary Egyptian art world?

Based on personal interviews with artists over many years of research in Cairo, Caroline Seymour-Jorn moves beyond current understandings of creative work primarily as a form of resistance or political commentary, providing a more nuanced analysis of creative production in the Arab world. She argues that in more recent years these young artists have turned their creative focus increasingly inward, to examine issues having to do with personal relationships, belonging and inclusion, and maintaining hope in harsh social, political and economic circumstances. She shows how Egyptian artists are constructing “spaces of hope” that emerge as their art or writing becomes a conduit for broader discussion of social, political, personal, and existential ideas, thereby forging alternative perspectives on Egyptian society, its place in the region and in the larger global context.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Creating Spaces of Hope by Caroline Seymour-Jorn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Kunst & Politik. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

EGYPT’S CHOIR PROJECT: SINGING AND PERFORMING SPACES OF HOPE

Introduction

The idea of the Choir is to get the people to sing their thoughts as a way of expression, but also as a sort of therapy. We put out a community notice for people to gather at a certain place, which is movable. Then we work collaboratively on a topic and put ideas into song. (Author interview with Salam Yousry, Cairo, January 18, 2012)

The Choir Project and the way the songs evolved and what they say . . . it gives a repertoire of how people have felt throughout the past few years. It’s very clear. (Choir participant and audience member, January 2018)

This chapter explores the creative production of Egypt’s Choir Project, a highly innovative and collaborative music and theater group that has provided a context for creative, social, and political expression for youth since 2010. Drawing upon Richard Bauman’s multifaceted framework for thinking about emerging art forms, I detail the history and sociopolitical context of the Choir Project’s activities during the period from 2011 until 2018, and engage in close literary analysis of some of its lyrical and dramatic production (Bauman 1984). Since the Choir has emerged and developed in a charged political environment, I take into account the important ways in which it has provided a context for political expression. However, I argue that detailed literary and social analysis of its creative process and production suggests that while the Project can be considered a mode of social and political expression or even resistance, it is also a profoundly creative phenomenon whose lyrical and dramatic creation must be attended to in its own right and which must also be understood as a powerful mode of personal and even existential expression. Indeed, I would caution against emphasizing the “resistance” element of this work, as this may eclipse the richness and multilayered nature of its creative innovation. I suggest that paying close attention to aesthetic experimentation and style adds an important dimension to our understanding of emerging art forms and the complex set of ideas that they express. Close analysis of the nature of innovative creativity may also help to explain why these forms have been so popular among audiences and the general public, even in the midst of political chaos and uncertainty about the future.7

I present here a brief history of the Choir Project and engage in a detailed analysis of my own ethnographic encounter with it, drawing upon verbal art theory to think about the creative ways in which Choir members have used language and paralinguistic elements to explore a variety of personal, social, and political topics. I combine my own observation of a Choir event with interview material with the project director Salam Yousry8 and participants, and with translation and analysis of lyrics from four songs and from an experimental play. I aim to show how the Project has become a politically viable and creatively compelling channel for expression of citizen concerns in pre- and postrevolutionary Egypt. This article is also based on observations of a January 2012 Choir event in Cairo and on the study of many taped productions made available on the Project website or by Yousry. It is further based on semistructured interviews conducted with Yousry and five participants in Cairo in January 2012, July 2015, and June 2018, and over Skype in 2018. Material was also gleaned from an informal gathering with participants after the January 2012 concert. These interviews and informal conversations provided useful information for understanding the personal meaning of this creative activity for participants.

An Introductory Sketch: The Choir Project

The Choir Project began before the January 2011 Revolution, but its early production was motivated by many of the issues that spurred that revolution. The Project was initiated in the spring of 2010 with an electronic community notice inviting people to gather for a workshop that would meet every evening for one week. During the workshop, participants would explore various themes relevant to the community and develop songs from these discussions, and then perform them publicly. The Project was inspired by the International Complaints Choir founded in Finland in 2005, which was also designed with the idea of converting the energy of people who were dissatisfied with their social and political environment into creative production that was at the same time an important form of community expression (author interview with Salam Yousry, Cairo, January 18, 2012). Under the direction of Yousry and fellow musician Motaz Atallah, the Choir provided the opening act for a show called Gamahir khafiya (Invisible Publics) and for an accompanying art exhibit at Cairo’s Townhouse gallery in May 2010 (Kelada 2015, 225).

The Choir’s initial presentation, entitled Kural shakawi il-Qahira (Cairo Complaints Choir) was composed of a number of songs that describe in elliptical terms some of Cairo’s major economic, social, and political problems. Two of these songs are available on the group’s website, with English subtitles.9 The complaints listed in the first song, Gharib fi Baladi (Estranged in my Own Land) are deadly serious, ranging from the inadequacy of garbage collection in Cairo to shortages of gas and the sad state of workers’ rights. But the performance is framed as an energetic and witty commentary and its humor lightens its tone and facilitates a critique that is both sardonic and serious. For example, singers perform in low voices, and there is considerable repetition of the lyrically articulated complaints. However, this serious tenor is balanced by the humorous rhyming lyrics that refer to the sometimes odd personalities and claims of TV performers and other public figures. One clever lyric takes a stab at the hypocrisy of Egyptian television preachers: “On TV a cleric announces with utter precision/That it is forbidden to watch television.”10 The song ends with a few lines that might be spoken by many Egyptians I know:

I’m a stranger in my own country

My rights are trampled on

All sense of justice gone

Banks in place of green spaces

All sense of justice gone11

My rights are trampled on

All sense of justice gone

Banks in place of green spaces

All sense of justice gone11

The Choir works mostly in the Egyptian colloquial dialect, and the contrast between this “low” form of language, the formality of performance, and the seriousness of the subject matter creates a paradoxical experience that demands the attention of the audience.12

According to Yousry, the management of Townhouse Gallery was not interested in continuing to host the Complaints Choir because at that particular time they wanted to stay away from creative production that expressed political critique.13 This is perhaps not surprising considering the fact that the gallery has historically been subjected to intimidation from the state for hosting politically and socially challenging artistic work. According to Samia Mehrez, the gallery, which is owned by the Canadian curator William Wells, has been targeted by multiple instances of

state-orchestrated intimidations that have ranged from accusations of exploitation and corruption of the national young crop to insinuations of entrepreneurial and colonial foul play, which have occasionally justified surprise raids and searches of the Townhouse premises by security forces, not to mention occasional censorship episodes of exhibiting artists’ work. (Mehrez 2008, 221)

Yousry himself wanted to take the Choir in another direction, away from the idea of complaint to a format with changeable themes. Indeed, since that initial performance in May 2010, the Choir Project has held workshops and performances on themes ranging from inflation and transportation problems, to the excesses of the advertising industry, the corruption of the Mubarak regime and subsequent governments, and the brutality of their security forces. Yousry has also conducted workshops and performances in London, Munich, Istanbul, Beirut, Paris, Berlin, Graz (Austria), Lebanon, Baku (Azerbaijan), Birmingham (England), Budapest, Cyprus, and Warsaw. However, most of the workshops have been held in Egypt: in Cairo, Alexandria, and smaller cities such as Luxor, Fayed, and Minya.

The Choir Project workshops and performances continue until today, and more recently, its activities have turned to the theatrical, with the production of an absurdist play called Zobaida (2018). According to Yousry and several participants who have been involved over the years, the groups convened for each event are mostly middle-class and include both Muslims and Christians. The demographics of participants change from one Choir to the next, but they tend to be college-educated individuals in their twenties and thirties who have diverse political and religious orientations. Each workshop has around twenty-five to thirty participants and an audience of variable size. According to Yousry, thousands of people have now participated in the workshops.

In addition to the shows, the songs have a virtual presence on the Project’s website, which is professional in its layout, content, and usability. The site features artwork embedded with song lyrics, and a carefully archived timeline of workshops with links to portions of productions. One can also find YouTube videos of many of the Choir shows over a span of several years, even without accessing the website. Most of these videos have between 300 and 2,800 views. The website allows access to the lyrics and music far beyond the actual stagings and allows those who have participated in past workshops—and those new to the Project—to listen to parts of multiple performances.

The website has also allowed for dissemination of the presentations during periods in which the group has experienced censorship of the clever, sometimes subtle, sometimes bold political commentary embedded in their lyrics. This censorship has occurred only a few times, with one notable instance during the early weeks of the 2011 Revolution, just before it performed its “Utopia” songs at the State Opera House. The political nature of the “Utopia” lyrics caught the attention of Mubarak’s state security apparatus, and according to one member, the Opera House management made moves to cancel the performance. According to this account, the group told the Opera House management that they would make a stink in the media if the event was canceled, and the show went on as scheduled. Nevertheless, after the “Utopia” Choir concluded, another member reported, “We faced some difficulties with state security, and we had to go underground a bit and many places wouldn’t allow us to perform” (Elkayal 2011). This participant refers to a period of heightened popular discontent over the loyalty of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces to the core of Mubarak’s regime in mid-2011. While the group was able to perform at the al-Fann Midan (Art is a Square) festival, which was held in the populous area of Abdin Square in Cairo, for the rest of that year the group performed at the Jesuit Cultural Centers of Cairo and Alexandria, venues that Yousry described as sympathetic to his project and that had management less skittish about possible regime critique or censorship. Throughout this time, the website served as a way for the group to extend its reach beyond the limited number of cultural spaces that open their doors to social, political, and cultural critique.

It is important to note that the Choir Project is part of a vibrant cultural scene in Cairo and Alexandria that includes art galleries, cafés, literary gatherings, experimental theater, and cinema. The multifaceted nature of this artistic and literary scene has been well documented elsewhere (e.g., A. Abdalla 2010; Jacquemond 2008; Mehrez 2011; Keraitim and Mehrez 2012; Shafik 2007; Swedenburg 2012). Although the current regime of President Abd al-Fatah al-Sisi has cracked down on youth artistic and intellectual activities by closing venues and making arrests—particularly in downtown Cairo—this vibrant artistic world has continued to operate. Because it draws upon a European choir phenomenon, the Choir Project might be viewed as engaging in a “Western” genre of artistic activity. Yet, as Steve Caton and Lila Abu-Lughod have demonstrated, verbal art in the form of recited poetry has a long history in Egypt and in the region generally and has been used to express important personal, social, and political concerns (Caton 1990; Abu-Lughod 1986).

Cairo also has an active community of poets who recite in both standard and colloquial Arabic, and music of all types is popular throughout the country. Theater has for decades existed in multiple forms, including the government or public-sector theaters that produce classic Western and Arab works, commercial theater that caters to tourists from the Gulf and to wealthy Egyptians, and alternative theater that produces more challenging experimental and political work. The Choir Project engages a new concept, but it does so in a cultural context already very attuned to poetry, song, and theatrical performances.

Performing the Future

I explore the activities and creative production of the Choir Project through the lens of verbal art theory as developed by Richard Bauman. Although there is a large body of research on verbal art in anthropology, I rely most heavily on Bauman’s approach, as it provides a useful means of knitting together textual analysis, observation of productions, and participant interviews (Malinowski 1935; Bateson 1972; Abu-Lughod 1986; Bauman and Sherzer 1989; Caton 1990; Kapchan 1996). In his anthropological approach to verbal art, Bauman argues for the importance of understanding the cultural and political context of performances, and also for the careful analysis of their linguistic and aesthetic aspects, framing, and keying. Drawing upon Goffman and Bateson, Bauman suggests that we should understand how individuals frame their performance; how they develop a specific interpretive context that provides the audience with clues for understanding its multilevel nature (Goffman 1974; Bateson 1972). This includes detailing how performers deploy language as insinuations, jokes, imitation, or even quotation as a way to help listeners understand ideas communicated in the text beyond the referential content of the performed words. Bauman argues that individuals use frames and other aspects of performative skill and virtuosity to create a performance that “calls forth special attention to and heightened awareness of the act of expression and gives license to the audience to regard the act of expression and the performer with special intensity” (Bauman 1984, 11). Bauman encourages us to think about how it is that performers develop their framing process and how they key their creative production; that is, how they might use linguistic features such as special codes, figurative language, or appeal to tradition to develop an inventive and compelling way to communicate a range of messages. The keying of the pie...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustration

- Acknowledge

- Introduction

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- Notes

- Bibliography