![]()

1

Extinction Risks from Anthropogenic, Ecological, and Genetic Factors

RUSSELL LANDE

SUMMARY. This chapter discusses the effects of both deterministic and stochastic factors on the risk of extinction. I begin by introducing the anthropogenic factors, such as land development, overexploitation, species translocations and introductions, and pollution, that are the primary causes of endangerment and extinction. These primary anthropogenic factors have ramifying ecological and genetic effects that contribute to extinction risk. I then discuss the role of ecological factors, including environmental stochasticity, random catastrophes, and metapopulation dynamics (local extinction and colonization). Genetic factors, such as hybridization with nonadapted gene pools and selective breeding and harvesting, also play a critical role. Especially important in small populations are the genetic factors of inbreeding depression, loss of genetic variability, and fixation of new deleterious mutations, as well as the ecological factors of Allee effect, edge effects, and demographic stochasticity. Finally, I consider the relative importance and interaction of these different risk factors, as they affect population dynamics and the threat of extinction.

INTRODUCTION

Many plant and animal species around the world are threatened or endangered with extinction, largely as a result of human activities. The frequent multiplicity of threatened and endangered species, even within local planning areas, has made it clear that effective conservation and restoration must be done in the context of comprehensive landscape and ecosystem approaches that consider biodiversity and large-scale ecological processes. Species-based approaches should nevertheless play an essential role in formulating and monitoring large-scale conservation and restoration plans to ensure that ecologically important species, or those that indicate ecosystem health, are properly managed. Understanding the factors that contribute to the extinction risk of particular species, therefore, remains of critical importance even within landscape and ecosystem approaches to conservation and restoration.

Anthropogenic factors constitute the primary causes of endangerment and extinction: land development, overexploitation, species translocations and introductions, and pollution. These primary factors have ramifying ecological, and genetic effects that contribute to extinction risk. For example, land development causes habitat fragmentation, isolation of small populations, and intensification of metapopulation dynamics. All factors affecting extinction risk are ultimately expressed, and can be evaluated, through their operation on population dynamics. Here I review anthropogenic, ecological and genetic factors contributing to extinction risk, briefly discussing their relative importance and interactions in the context of conservation planning.

1.1 ANTHROPOGENIC FACTORS

Land Development

Human population growth and economic activity convert vast areas for settlement, agriculture, and forestry. This results in the ecological effects of habitat destruction, degradation, and fragmentation, which are among the most important causes of species declines and extinctions. Habitat destruction contributes to extinction risk of three-quarters of the threatened mammals of Australasia and the Americas and more than half of the endangered birds of the world (Groombridge 1992, ch. 17).

Overexploitation

Unregulated economic competition

Inadequately regulated competition among resources extractors, especially in open-access fisheries and forestry, is one of the major causes of resource overexploitation and depletion (Ludwig, Hilborn, and Walters 1993; Rosenberg et al. 1993). About half of the fisheries in Europe and the United States were recently classified as overexploited (Rosenberg et al. 1993). Hunting and international trade contributes to the extinction risk of over half of the threatened mammals of Australasia and the Americas and over one-third of the threatened birds of the world (Groombridge 1992, ch. 17) and has caused local extinctions of many forest-dwelling mammals and birds even in areas where habitat is largely intact (Redford 1992).

Economic discounting

A nearly universal economic practice is the discounting of future profits. Annual discount rates employed by many governments and resource exploiters are often in the range of 5% to 10% or higher. Clark (1973,1990) showed that in many cases there is a critical discount rate above which the optimal strategy from a narrow economic viewpoint is immediate harvesting of the population to extinction (liquidation of the resource). In simple deterministic models with a constant profit per individual harvested, the critical discount rate equals the maximum per capita rate of population growth, rmax, because money in the bank grows faster than the population (May 1976). Organisms with long generation time and/or low fecundity, such as many species of trees, parrots, sea turtles, and whales, have rmax below the prevailing discount rate and are frequently threatened by overexploitation.

Stochastic fluctuations in population size reduce sustainable harvests (Beddington and May 1977; Lande, Engen, and Saether 1995). Optimal harvesting strategies that reduce extinction risk as well as maximize sustainable harvests have only recently been developed. Such harvesting strategies generally involve threshold population sizes below which no harvesting occurs when the population fluctuates below the threshold (allowing the population to increase at the maximum natural rate), and above which harvesting occurs as fast as possible (Lande, Engen, and Saether 1994, 1995; Lande, Saether, and Engen 1997).

Introduction of Exotic Species

Numerous species are transported and released in foreign environments both accidentally and deliberately in private and commercial transportation, live-animal trade, ornamental plantings, and biological control. Introduced species, mainly predators and competitors, seriously affect about one-fifth of the endangered mammals of Australasia and the Americas and birds of the world (Groombridge 1992, ch. 17). Introduced rats are responsible for extinctions of many island-endemic birds (Atkinson 1989). In some national parks in Hawaii, up to half of the plant species are nonnative (Vitousek 1988) and constitute a serious risk for the endangered flora. Introduced strains and species of parasites and diseases also pose a serious problem for many endangered species (Dobson and May 1986).

Pollution

Agricultural and industrial pollution have had both localized and widespread effects. Long-lasting pesticides, such as DDT, become concentrated in terrestrial and aquatic food chains, and have endangered several birds of prey, such as the American bald eagle and peregrine falcon. Although bans on most long-lasting pesticides in the United States helped recovery of both these species, the pesticides are still used in many countries. About 4% of endangered birds of the world and 2.5% of mammals of Australasia and the Americas are at risk from pollution (Groombridge 1992, ch. 17). These figures underestimate the extent of morbidity, mortality, and fertility impairment caused by pesticides in many non-endangered species.

Acid rain has had intense regional effects on terrestrial plant communities in Western Europe and on freshwater ecosystems in the eastern United States. In Germany, about one-fourth of the native species of ferns and flowering plants are endangered or extinct, with about 5% affected by air and soil pollution and 5% by water pollution (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [ODEC] 1991).

1.2 ECOLOGICAL FACTORS

Environmental Fluctuations and Catastrophes

Unexploited vertebrate populations fluctuate through time with coefficients of variation (standard deviation/mean) in annual abundance usually in the range of 20% to 80% or more (Pimm 1991). Exploited populations also are highly variable (Myers, Bridson, and Barrowman 1995), due not only to environmental stochasticity, but also because commonly used exploitation strategies, such as constant-effort or constant-rate harvesting, tend to reduce population stability (Beddington and May 1977; May et al. 1978). Catastrophes are an extreme form of environmental fluctuation in which the population is suddenly reduced in size by a large proportion, usually because of extraordinary climatic conditions such as droughts or severe cold or because of disease outbreaks (Young 1994).

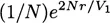

In stochastic population models with density-dependence and either normal environmental fluctuations in population growth rate or random

| Risk Factor | Proportional scaling of T |

| Declining population1 | |

| Environmental stochasticity2 | |

| Demographic stochasticity3 | |

| Fixation of new mutations4 | |

1 In this case only, mean population growth rate,

is negative.

2 Mean and variance of annual growth rate are

,

Ve respectively.

3 Mean and variance of individual Malthusian fitness are r, V1, respectively.

4 c is the coefficient of variation of selection against new mutations.

Table 1.1. Asymptotic scaling laws for mean time to extinction, T, from different ecological and genetic risk factors, as a function of the initial actual size, N, or effective size, Ne, of a population at carrying capacity.

catastrophes, for a population initially near carrying capacity the mean time to extinction, T, scales asymptotically (for sufficiently large populations) as the carrying capacity raised to a power. Depending on the magnitude of environmental fluctuations in population growth rate, or on the frequency and magnitude of catastrophes, this power may be either greater than or less than one. Thus, comparing populations with different carrying capacities, under low environmental stochasticity, T increases faster than linearly with increasing carrying capacity, whereas under high environmental stochasticity, T increases less than linearly with increasing carrying capacity (Lande 1993). Logarithmic scaling of T with initial population size is characteristic of a declining population, in which the mean growth rate is negative, regardless of whether the decline is deterministic or stochastic (Lande 1993). Asymptotic scaling laws for various risk factors are summarized in Table 1.1.

If population subdivision substantially reduces the correlation in environmental stochasticity among localities, for example, considering one large contiguous reserve versus several small distant reserves of the same total area, then subdivision can increase T. Thus, in a case when single populations are subject to major catastrophes, occurring randomly among populations, then population subdivision can clearly be advantageous for persistence (Burkey 1989). Subdivision also can increase persistence in the presence of catastrophic epidemics, not only by reducing the transmission of epidemics among localities, but in some cases by reducing their frequency because many epidemics require a threshold population size or density to become started (Hess 1996). On the other hand, if the small reserves are located in the same general area, and are subject to nearly the same environmental stochasticity, then subdivision is likely to decrease persistence by making the small reserves more subject to edge effects, Allee effects, and demographic stochasticity.

Above the species level, ecosystem function is likely to be enhanced in large reserves without landscape fragmentation; species diversity would tend to be larger, at least initially, in several small reserves spread over a larger geographic area, but these would suffer more rapid local extinctions. Designs for nature reserves systems must balance these advantages and disadvantages of subdivision. From a review of data on several natural and artificial archipelagoes, Burkey (1995) concluded that on a single large island the rate of species extinctions is initially faster, but ultimately slower, than on several small islands.

Metapopulation Dynamics

Dispersal among local populations, patches of suitable habitat or "islands" also can have advantages and disadvantages for persistence. The major advantage is that dispersers can recolonize suitable habitat after local extinctions, a...