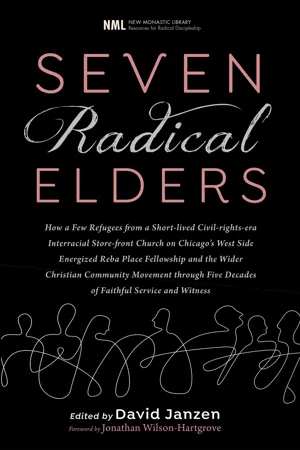

![]()

one

Julius Belser

Toolbox-Toting Visionary of Interracial Community

I. Growing Up

My mom grew up on a farm near Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania. My parents were both the youngest in their families. Mother and Dad met when they were working at Reese’s Candy Company. Mother would take a spoon of peanut butter from a hot slab of marble, and then dip it in chocolate and put it in a peanut butter cup. My dad worked at the same factory doing maintenance, fixing all kinds of things.

My dad’s family lived in Hershey, across the street from the Reese family. He grew up with the Reese family’s twelve kids. The Reese family had an advertisement on the back of their candy box: “Twelve reasons why you should buy Reese’s candy” and a picture of their family.

Dad was a skilled tinsmith. My grandfather learned his tinsmith trade in Germany before he came over in the 1880s. My grandfather had a very short temper: he was German. My dad had some of that too. My father grew up in a German Lutheran family. My mother was a devout member of the Church of the Brethren. My dad joined the Church of the Brethren when they got married. At that time, he took off his ruby ring, a ring with a red stone in it. The Church of the Brethren was a plain people, so wearing jewelry was not good.

I was born on March 15, 1931, and for that reason was named Julius, after Julius Caesar who was murdered on “the Ides of March.” I was followed by four other siblings, Vernon, Ruth Anne, Jim and John. As the firstborn I grew up feeling over-responsible for whatever happened in our family.

Our family was very concerned that my father might be drafted to fight in World War II. Fortunately, he had started working for the Hinkle Company, making metal tins, sifters, and elevator buckets—“feeding the nation.” He and his brother were both skilled sheet metal workers and had previously run their own machinery company. Though he was no longer in business for himself, his work for Hinkle was classified as “high priority,” and he was not called to fight in the war.

My mother impressed me with her orientation towards the Bible and prayer: she had a real assurance that God does answer prayer. She’d read to us from Hurlbut’s Story of the Bible for Children. My mother prayed regularly. She listened to radio preachers and she sent for blessed handkerchiefs from them. So my orientation to prayer and the Bible came heavily from Mother. I came to love God because of my parents.

Dad was a good craftsman who knew how to work hard and have fun. We’d get up on a hot tin roof and work together. After we’d lay out the tin and put it on, the reflection of the sun just came right up in our faces and we’d get a sunburn. We would work together up above the second or third floor and then go down and get a liter of soft drink and really have a nice break. I remember sharing the deep things of my life with Dad while we worked, like telling him that I really wanted to get married to Peggy. I enjoyed working with Dad, and he enjoyed us kids. He had patience with a lot of things, although not as much patience with Mother.

My mother was a fearful, sometimes paranoid person. During the summer, Dad worked hard and accumulated quite a bit of money. During the winter, he didn’t have outside work, so his savings were all eaten up. Mother had a lot of desires for things; she and Dad fussed about money and other basics. She was concerned that my dad was interested in other women. It wasn’t true but they’d fuss. Eventually, they bought a little farm, four and a half acres out on the top of the hill overlooking Elizabethtown. My parents loved us kids, and they did all they could to care for us.

Growing up, the biggest concern of my life was the conflict between my parents. At twenty years old, I felt helpless and asked for God to intervene in what seemed like a hopeless situation. The level of conflict seemed to increase despite my attempts to help out around the house and ease the strain. I worried about whether they’d separate and get divorced. Finally, I came to a peaceful place, leaving it to God whether they’d stay together or separate. The “Red Sea” experience in my life, the parting of the waters, was when my parents drove down the road to see a counselor, Robert Eschelman, one of my college teachers who I thought could be helpful for them. It was the answer to years of praying for them.

I’ve read Karl Lehman’s book The Immanuel Approach about prayer therapy. In the book, Karl Lehman talks about establishing an anchor to a positive memory that helps you build a positive relationship with God. For me, this memory of my parents leaving to see a counselor is that experience of God’s deliverance that I go back to and remember how God led us through it. It wasn’t just a personal experience: it was the healing of my family. After that, there were still lots of conflicts between them, but I knew it wasn’t the end of their marriage.

Our church was in a very agricultural society, with community and the nitty-gritty of life all bound together. Though we were middle class, our concerns reached beyond our own welfare. The work of the Brethren Voluntary Service was very central in our church life: caring for refugees and sending disaster relief to third-world countries.

Dan West was a very peaceful and successful man in the Church of the Brethren; I knew him personally. He went over to Spain during their civil war, and what he witnessed there turned him off to the whole business of war and, eventually, inspired him to found Heifer International. He inspired me too. In high school, my constant talk about peace and the joy of Christ earned me the nickname “One World Belser.” During World War II when others were selling the customary war stamps, I decided to buy Brethren service stamps. Integrating faith, everyday life, and action for justice would become a theme throughout my years.

One of my most special relationships was with Harvey and Violet Kline. Violet was a sister to my mother. I spent my summers on Uncle Harvey’s farm near Lebanon, Pennsylvania. I rode a bicycle (two hours) over there one time. We had so many good events in their front yard playing croquet or playing softball. We’d get ice cream on Sunday nights at Zigler’s: twenty-five cents a quart of homemade ice cream at special celebration times. My cousin Harvey was a pre-ministerial student. He was ten years older than me and influenced me very strongly. He was my role model.

II. Courtship and Marriage

I met Peggy because she was part of our congregation. In 1948, just after finishing high school, I went with Peggy’s family to the Church of the Brethren annual conference in Colorado Springs. During that trip I felt more comfortable with them and with Peggy in particular. I pursued the relationship. Peggy took a year off college to volunteer with Brethren Voluntary Service as part of a “peace caravan” that went to the different churches, championing the peacemaking vision of the Brethren.

I did a little dating when I was just beginning college. Peggy and I were still writing to each other. As it turned out, at one point I had a date with Mary Greenwalt to go to a district Church of the Brethren conference, and Peggy let me know she was coming home that weekend. So, I had to decide [Julius starts laughing] . . . I had to decide just how serious our relationship was. At another time, a Church of the Brethren ministerial student approached me in college, wanting to know how serious I was about Peggy. I made it clear that I was pretty serious. When she came back from her year away, her experiences had introduced her to the Church of the Brethren and its peace witness in a much more radical way. That radical inclination seemed really right to both of us. At a certain point, we had done so many things together, our relationship had quite matured. Peggy graduated a year ahead of me, but she was ready to wait until I finished college. Then I was ready to marry her.

III. Seminary and Community Action in Chicago

I went to the Church of the Brethren Seminary in Chicago because it was the only seminary of our denomination. There I was impressed by a recently returned missionary who lived a life of courage in the Lord, a deep joy that overcame fear. She had been hired as a caretaker for Prime Minister Nehru’s children in India. I remember that she had a very bold laugh and was deeply interested in Christian community. Her brother and his family were part of the Society of Brothers, or Bruderhof.

My Bethany classmates and I had already been in considerable dialogue with the Bruderhof about Christian community. One of my classmates, Bob Wagner, visited a Bruderhof community in Paraguay that had fled to escape the Nazis before the War. He came back saying, “This is the closest thing to the New Testament I’ve ever seen, the way they lived together . . . the way they loved one another.” The thrust of that community was very impressive to him. Four couples out of our graduating class left to be a part of Bruderhof communities instead of taking pastorates in local churches. We all visited them, and I was very impressed, but their communities were only located in isolated places like rural New York.

My calling was to start a community like that in the inner city—in Chicago. I thought that the healing power of their community needed to be planted in the raw, sore heart of the city. I was inspired, just the same, and began to consider ways of bringing their presentation of the gospel to the places that needed it the most.

When I first came to Chicago and to seminary, Archie Hargraves, a Black pastor, visited the seminary and spoke in chapel. He had a vision of church as community, as a part of the broader city life, engaged with local politics and leadership of the neighborhood. Archie’s vision combined Brethren Voluntary Service work and home missions (establishing new congregations). He didn’t just want to give stuff out to needy people but wanted the church life and the gospel to be at the center of the ministry. He visualized the church on every block, organizing the community. It sounded so right! I came home that day, after he spoke in chapel, and told Peggy about it, saying, “This is it. I want to be a part of this.”

Beginning in 1953, I spent two years at the Lawndale Community Church working part-time as my practical work for seminary. This was a Presbyterian congregation with only a handful of mostly White members left (about eight or ten of them). The West Side Christian Parish, where Archie was a leader, gave some money to revitalize this congregation that was in a neighborhood that had just gone from total White to total Negro in five years. The whole neighborhood was in turmoil. The Presbytery invited the West Side Christian Parish to take charge of the church. The Parish assigned Archie Hargraves as pastor. It was his vision to invite t...