![]()

Chapter 1

Normal and Abnormal Heart Function

Learning more about the heart's normal structure and anatomy may help you understand why different heart problems occur and the conditions that may lead to the need for an implanted device.

BASIC CONCEPTS OF CARDIAC BLOOD FLOW

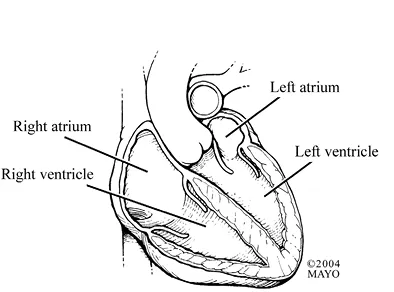

The heart is often described in terms of two concepts: “plumbing” and “electrical.” The heart is, by definition, a pump. There are four chambers in the heart (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Normal heart.

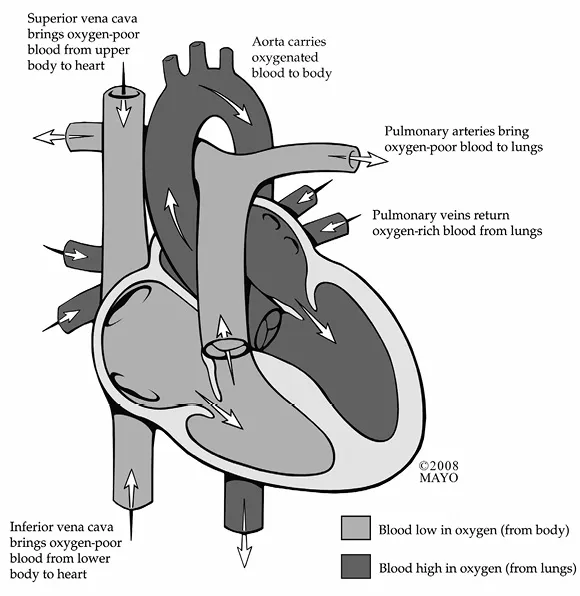

The two chambers on the top are the atria (singular: atrium), and the two bottom chambers are the ventricles. Although every part of the heart is important, the left ventricle is responsible for pumping blood throughout the body, and it therefore plays a vital role in blood circulation. When the left ventricle squeezes, the blood exits the heart through the aortic valve into a large blood vessel, the aorta. From there, the blood travels to all parts of the body (Figure 2). The blood leaving the left ventricle is rich with oxygen, which the rest of your body needs to stay healthy. As the blood goes through the aorta to other arteries and progressively smaller blood vessels, some of the oxygen in the blood leaves the red blood cells to nourish the body's tissues. The oxygen-poor blood then enters the veins and is routed back to the right side of the heart.

The blood enters the right atrium and then passes through a valve called the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle. When the right ventricle contracts or squeezes, the blood travels through the pulmonic valve into blood vessels in the lungs. In tiny vessels in the lungs, oxygen can pass back into the blood cells. Oxygen-rich blood then re-enters the left atrium (the top chamber on the left side of the heart) and goes through the mitral valve into the left ventricle, where the process starts all over again.

Figure 2. Normal cardiac blood flow.

A very important term to be familiar with is the phrase left ventricular ejection fraction, abbreviated as LVEF or, sometimes, just EF. The LVEF is defined as the percentage or fraction of blood that the left ventricle squeezes out with each beat. Different hospitals and laboratories may use slightly different values for a “normal” LVEF. In general, a normal LVEF is 50 to 60% (See Figures 1 and 3). Some patients intuitively think that all the blood should be squeezed out, and that the LVEF should be 100%, but that would definitely not be normal or healthy. A desirable LVEF percentage is 50 to 60%.

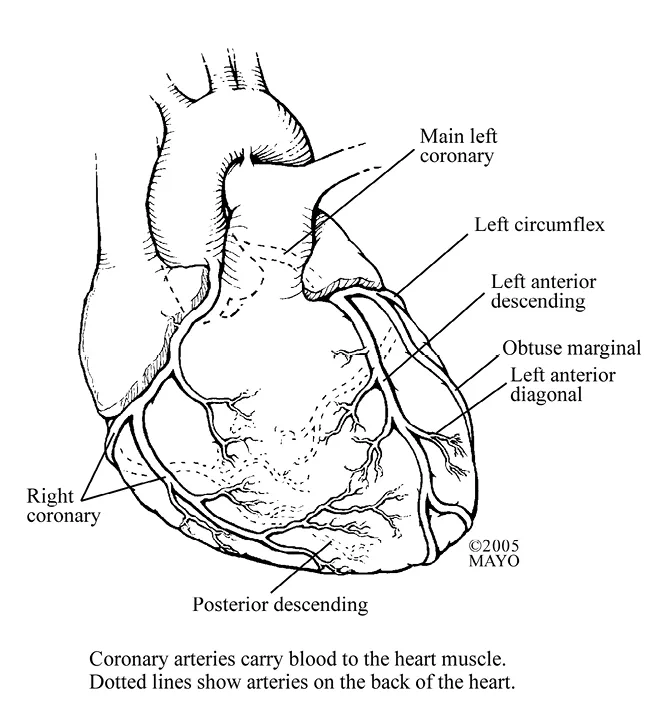

The main function of the heart is to pump oxygen-rich blood throughout the body and then return the oxygen-poor blood to the lungs to regain oxygen. However, the heart itself also needs blood supply. The coronary arteries supply the heart muscle with oxygen-rich blood. The coronary arteries come off the aorta, just above the heart valve from which blood exits the left ventricle (Figure 4). There is a right coronary artery and a left main coronary artery, which divides into two main branches: the circumflex coronary artery and the left anterior descending coronary artery. Although there can be many variations in the anatomy of the arteries, in general,

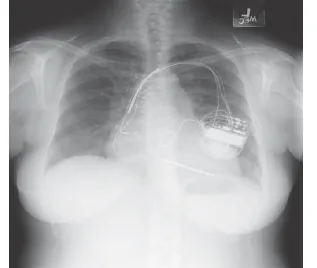

Figure 3. Figure 1 shows a diagram of the heart with normal ventricular size and normal wall thickness. With normal function the left ventricular ejection fraction should be 50% to 60%. By contrast, the chest x-ray featured in Figure 3 is from a patient with severe enlargement of the heart and the ejection fraction would be much below the normal limits.

- the right coronary artery supplies the back wall (or inferior wall) of the left ventricle;

- the left anterior descending coronary artery comes down the front wall (or anterior wall) of the left ventricle and often supplies blood to the tip or apex of the left ventricle; and

- the circumflex coronary artery circles around to the outside (or lateral wall) of the left ventricle.

Figure 4. Coronary arteries.

Each of these main arteries has a number of branches, some of which can be quite large. That's why you may hear of someone having bypass surgery that involved four or five arteries being bypassed. What this probably means is that all three main coronary arteries were bypassed, and in addition, one or more main-branch vessels were bypassed.

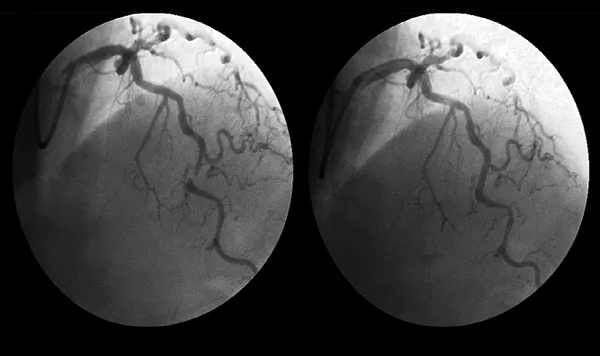

Bypass procedures are performed by a cardiovascular surgeon. However, if only one or two blood vessels have blockages, the common treatment is to open the blockage with a balloon and often also to place a stent in the artery to keep it open (Figure 5). These “interventional” procedures are usually performed by cardiologists, specifically, interventional cardiologists. They will sometimes be referred to as the “plumbers” because they open the “pipes” to get blood to the heart muscle.

Figure 5. Coronary artery before and after blockage removal as noted by arrows.

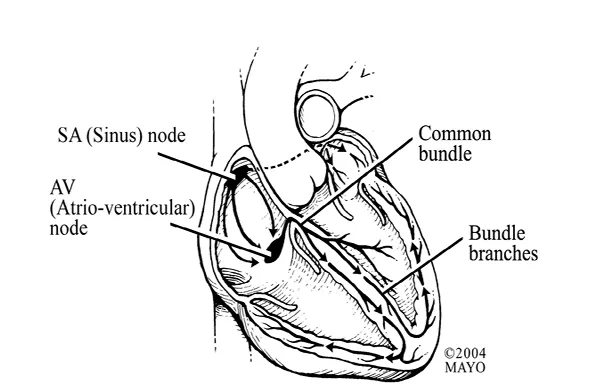

The heart is able to pump because it is energized by its own electrical system. Remember the atria, right and left, are the top chambers of the heart. Located in the atria is very specialized tissue that forms the top “electrical switch.” This is called the sinus node, and this is where the electrical impulse for the heart originates (Figure 6). When the sinus node “fires” or discharges, an electrical impulse is sent through both the right and left atria, resulting in the atria squeezing or “contracting.” After traveling through the atria, the electrical impulse reaches more specialized tissue called the atrioventricular (AV) node. The AV node is a collection of cells located between the atria (A) and the ventricles (V), acting as somewhat of a relay switch. After passing through the AV node, the electrical impulse travels throughout the ventricles and results in ventricular squeezing, or contraction. More specifically, there are two main branches of electrical activation that come out of the AV node, called the right bundle branch and the left bundle branch. These branches carry the electrical impulse that results in ventricular activation.

Cardiologists who treat electrical problems of the heart are called electrophysiologists (e-leck-tro-fizz-e-ol-o-gists) or the “electricians” of the heart. If an implantable cardiac device is needed to help regulate the heart's electrical system, it is usually implanted by an electrophysiologist.

Figure 6. Conduction pathways.

PROBLEMS WITH THE ELECTRICAL SYSTEM OF THE HEART

If you are reading this book, you, or someone close to you, may have an electrical problem with your (or their) heart. When you are talking to your caregivers, whether it is a nurse, technician, family doctor, cardiologist, electrophysiologist, or surgeon, a number of terms may be used that may be very confusing. (Throughout this book, we will usually refer to whoever is taking care of you or your loved one as the caregiver, realizing it can be one of many healthcare professionals.) You should feel comfortable taking this book with you when you talk to your caregivers, and if a term doesn't make sense or doesn't completely match up with the terms that are described below, speak up and ask them to clarify or explain what they mean.

Important Terms Explained

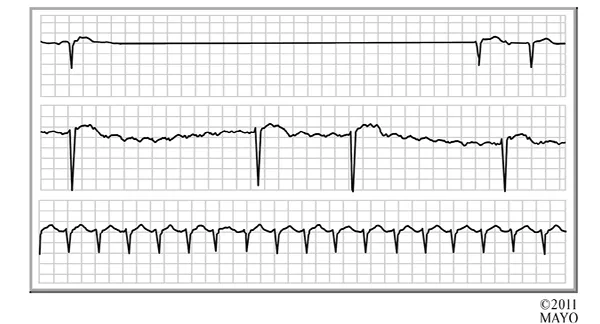

The terms sinus node disease and sinus node dysfunction are usually used interchangeably and simply mean there is a problem with the sinus node that was described above. Sinus node dysfunction may lead to slow heart rhythms (bradycardias) and/or fast heart rhythms (tachycardias). Sometimes the term tachycardia-bradycardia syndrome (or tachy-brady syndrome) may be used to describe sinus node dysfunction (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Tachy-brady syndrome.

Sinus bradycardia simply means that the regular heart rate, determined by the sinus node, is slower than normal. What is “normal” depends on your age and your physical condition. An infant or small child normally has a faster heart rate than an adult. For an adult, a heart rate less than 60 beats per minute is technically considered sinus bradycardia. That is not to say, however, that all heart rates less than 60 beats per minute are a problem. Many adults, especially adults in good physical shape, may have resting heart rates in the 50s or even the 40s. In general, men have slower heart rates than women, and in general, our heart rates are slower at night when we are asleep. Slow heart rates usually do not require treatment unless they lead to symptoms, such as fatigue, lightheadedness, or decreased ability to do physical activity.

Sinus tachycardia means that the heart rate, as determined by the sinus node, is faster than normal. By definition, a tachycardia is a sinus rate greater than 100 beats per minute when you are at rest. Again, there will be variations. A rate of 100 in a very small child or infant may not be abnormal. If you are exercising or feverish, the heart rate will go up, and that's to be expected. Sinus tachycardia usually doesn't require treatment, although in some patients, a medication may be used.

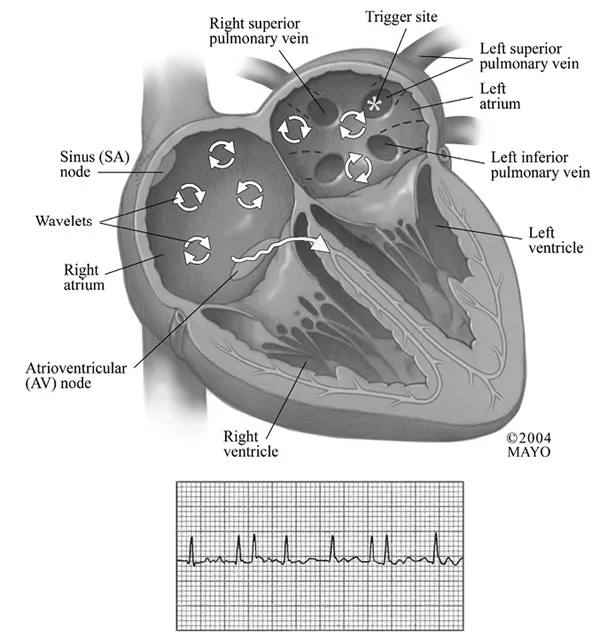

Atrial fibrillation is a condition where there is irregular, rapid electrical activity in multiple areas of the atria. Atrial fibrillation may occur if the sinus node is abnormal and loses complete electrical control of the atria. During atrial fibrillation, the upper chambers of the heart are literally quivering (Figure 8). In this condition, there is absolutely no organized electrical activity of the upper chambers of the heart. Atrial fibrillation may lead to a very irregular beating of the ventricles because the atria are completely out of rhythm. If you experience atrial fibrillation, you may be aware of a fast and/or an irregular heartbeat.

Figure 8. Atrial fibrillation.

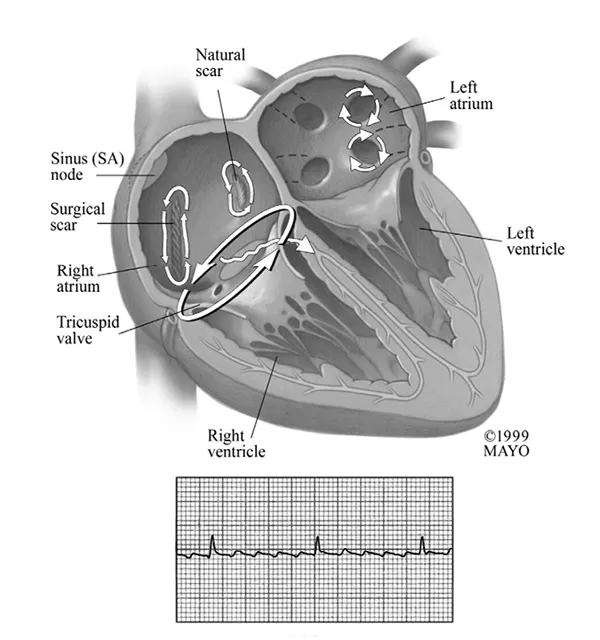

Atrial flutter occurs when, instead of normal rhythm dictated by the sinus node, a more rapid and regular electrical activation of the top chambers of the heart results from continuous loop or pattern of electrical activity in the atria (Figure 9). Both atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation have the potential to result in your pulse going very fast, which may sometimes cause symptoms that need to be treated. Atrial flutter is a more organized electrical circuit in the atria, compared to atrial fibrillation.

Figure 9. Atrial flutter.

Heart block is a term you may hear your caregivers using, but it refers to an electrical block, and not a blockage in the arteries. To make it even more confusing, there can be several different types of heart block. Some types of heart block are problematic and require treatment, often with an implantable device, while other types of heart block are of no consequence and require no treatment. Therefore, it's worthwhile to explain the different types.

Types of Heart Block

First degree heart block refers to a very slight increase in the time it takes for an electrical impulse to leave your sinus node, electrify the atria, and get through the AV node. This delay is very short, literally thousandths of a second. Many people have a first degree heart block and, by itself, it is not concerning and does not require treatment.

Second degree heart block occurs when the electrical impulse is significantly delayed in getting through the AV node to the ventricles. Sometimes the delay is so long that the impulse does not make it through the AV node at all. This can result in “dropped” or “missed” heart beats since the ventricles do the majority of the pumping function of the heart. Patients with second degree heart block may miss only occasiona...