- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

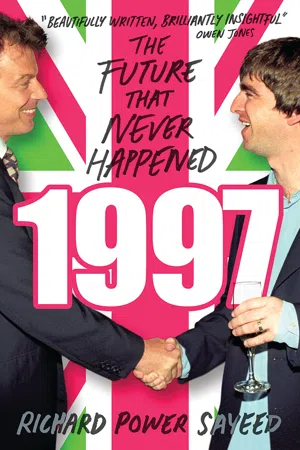

'Beautifully written, brilliantly insightful'

Owen Jones

Tony Blair and Noel Gallagher shaking hands at No. 10. Saatchi's YBAs setting the international art world aflame. Geri Halliwell in a Union Jack dress. A time of vibrancy and optimism: when the country was united by the hope of a better and brighter future. So why, twenty years on, did that future never happen?

Richard Power Sayeed takes a provocative look at this epochal year, arguing that the dark undercurrents of that time had a much more enduring legacy than the marketing gimmick of 'Cool Britannia'. He reveals how the handling of the Stephen Lawrence inquiry ushered in a new type of racism. How the feminism-lite of 'Girl Power' made sexism stronger. And how the promises of New Labour left the country more fractured than ever.

This lively, rich and evocative book explores why 1997 was a turning point for British culture and society - away from a fairer, brighter future and on the path to our current malaise.

Owen Jones

Tony Blair and Noel Gallagher shaking hands at No. 10. Saatchi's YBAs setting the international art world aflame. Geri Halliwell in a Union Jack dress. A time of vibrancy and optimism: when the country was united by the hope of a better and brighter future. So why, twenty years on, did that future never happen?

Richard Power Sayeed takes a provocative look at this epochal year, arguing that the dark undercurrents of that time had a much more enduring legacy than the marketing gimmick of 'Cool Britannia'. He reveals how the handling of the Stephen Lawrence inquiry ushered in a new type of racism. How the feminism-lite of 'Girl Power' made sexism stronger. And how the promises of New Labour left the country more fractured than ever.

This lively, rich and evocative book explores why 1997 was a turning point for British culture and society - away from a fairer, brighter future and on the path to our current malaise.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 / NEW LABOUR, NEW BRITAIN

Prince Charles was puzzled as to why his seat was so uncomfortable. After boarding this chartered flight to Hong Kong, he had, along with his team, sat down on its upper deck. ‘It took me some time to realise that this was not first class(!),’ he wrote in the journal that he would send to a large number of friends and relatives, and which was, to be fair to the prince and his perception of the aircraft seat, frequently inflected with irony. Downstairs an array of officials, senior members of the government and former prime ministers were sitting, marginally more comfortable than the prince, in first. His Royal Highness remained in business class all the way to Hong Kong. ‘Such is the end of Empire, I sighed to myself.’

On New Labour’s watch, the symbols and institutions of an old and deeply divided country were supposedly being reformulated. A new nation seemed just around the corner, for the government’s foreign strategy, long decried as reactionary and cynical by liberals, was being replaced by an agenda that some now described admiringly as ‘internationalist’,1 the country’s inequitable constitution was being reconstructed in an attempt to make England less dominant within the United Kingdom while ensuring that its union did not split, and a society dominated by the aesthetics and mores of its white majority seemed to be becoming ‘multicultural’.

Towards the end of 1997, a small political crisis would indicate that this liberal turn had a reactionary edge, although few outside the hard left perceived it at the time. Nearly a decade and a half before the ‘migrant crisis’ that began in 2015, New Labour would be faced with its first taste, both of thousands of people struggling to find a safer and happier home in Britain, and of the angry response those new arrivals received. The government’s reaction would quietly signal that their liberal vision for Britain was already dissolving.

As Prince Charles ironically recognized in his diary, the demise of the British Empire had already begun – in the late nineteenth century, actually – and now, in 1997, the United Kingdom had only seventeen ‘dependent territories’, as its colonies were known. Hong Kong’s sovereignty was among the most disputed of all these territories, partly because it was by far the most populous (more than six million people lived there, compared to the rough total of 160,000 living in the other dependent territories) and because, to a similarly dramatic degree, it was the richest of them. It was so wealthy that it was forced to send a remittance back to the UK.2

The Prince of Wales was on his way to Hong Kong because, in three days, at midnight on 30 June, the UK was going to hand control of the island and its surrounding areas to the Beijing government. The meaning of this event was clear to many observers,3 and to some it was disturbing, for the prince had been half right, even if he had been joking. The UK would still have protectorates and military bases in many regions across the globe. Indeed, its influence and control would continue to extend far beyond those relatively small territories. But Britain would no longer see itself as an imperial power.

The foundations of the United Kingdom would be remade that night in Hong Kong, and these changes were lamented by some, like Charles, for whom patriotism and national identity remained strong, albeit confused. That was exactly why others, like New Labour, saw in these developments an opportunity to channel the churning waters of national sentiment into the project of market globalization. If they spied any danger in using the nation to empower those global forces that could destroy it, they did not let it stop them.

Hong Kong had come under British rule during the First Opium War, during which Queen Victoria’s forces had compelled China to accept British imports of the drug. Now, the UK government’s lease on the New Territories, which formed the greater part of Hong Kong’s landmass, was at an end. Most of the city was built on land that the British government was not legally obliged to cede, but given that Beijing could easily have turned off Hong Kong’s water and energy supplies, it was not surprising that the UK had agreed to return all of its territories in the area to China. That did not, however, stop them from making things difficult for the Chinese. As the handover had neared, some British officials, particularly British governor Chris Patten, had become increasingly keen on allowing Hong Kongers a modicum of democratic freedom.

But now the day had arrived, and it would be an extraordinary media spectacle. Nearly 8,400 journalists from 775 news organizations were estimated to be reporting from Hong Kong on the coming days’ events.4

On TV sets around the world, the greenery creeping over the portico of Government House dripped with condensation and warm drizzle. Rising up behind its white neoclassical façade, viewers could see glimpses of the shining glass and steel trunk of the Asia Pacific Finance Tower. The voiceover of the BBC’s correspondent, Matt Frei, described the events on the evening bulletin: ‘One last leaving ritual from the governor: his car circled the courtyard three times, a Chinese custom that means “hope to be back”.’

The press had been told that this was what would happen, and indeed both the television reporters and the next day’s papers stated that was what had taken place, but Chris Patten, who was distressed by the prospect of his imminent departure, seems to have given his chauffeur different instructions. His black Rolls-Royce entered the driveway and circled it once, and after Patten and Lavender, his wife, got into the car, it travelled around the driveway only twice before leaving the compound.5 The car would, indeed, be returned to the mansion, but the British were never coming back.

At about 16.30, Mr and Mrs Patten arrived at the Royal Yacht Britannia with their three teenage daughters, somewhat creepily dubbed Posh, Sexy and Baby by Private Eye after three of the Spice Girls.6 Prince Charles would recall that the family looked ‘incredibly sad and somewhat shattered’. Patten was still cradling the Governor’s Flag, a Union Jack featuring the governor’s coat of arms that had, only half an hour before, flown above his official residence. Charles described how he ‘tried to soothe their nerves with a cup of tea’ before the party left again, this time for a farewell ceremony for British Hong Kong troops.

As the sun set, warm rain poured down on the Tamar Site, a vast plane of concrete that sat beside the harbour, and on which stadium terraces had been erected. ‘Today is cause for celebration,’ declared Patten to those assembled, ‘not sorrow.’ As his ash-blond hair fluttered in the breeze, however, he admitted both that he felt some sadness, and that imperial rule had involved ‘events … which would, today, have few defenders’. Nonetheless, he continued by describing British occupation in terms of its rule of law, rather than its lack of democracy. As the sky poured down on the British ceremony, Patten sometimes struggled to hide his emotions. ‘Now, Hong Kong people are to run Hong Kong. That is the promise and that is the unshakeable destiny.’ As the crowd roared with applause, Patten sat down beside Prince Charles, looking shocked and a little winded. His head fell and he studied the floor. The applause continued. He bit his lips.

Sat on the other side of the governor, Tony Blair had an embarrassed look on his face.7 His press secretary, Alastair Campbell, sitting a few seats away, had a similar reaction. ‘I felt Patten was overdoing the emotional side of things,’ the spin doctor recorded in his diary. ‘He gave the impression it was a personal act being committed against him.’8

Other elements of the British establishment felt differently about Patten’s eulogy for British rule. ‘I ended up with a lump in my throat,’ recalled Charles, ‘and was then completely finished off by the playing of Elgar’s Nimrod Variation.’ A small orchestra was working its way through the famous Adagio. Television viewers watched the musicians sat on a small temporary stage, surrounded by the crumpled and rain-sodden protective plastic sacks that they had, just a moment before, whipped off their instruments. As the trembling music rose, screens around the world flicked from one shot to another and viewers saw a vast harbour in the gloom, the lights of great ships bobbing in the mist and rippling waves that sparkled in the moonlight. The heaving momentum of the horn section forced the orchestra into a thunderous swell of timpani and strings, and the camera pulled out slowly to reveal the majestic neon-bannered towers of Causeway Bay. At the moment that the instruments exploded into their resurgent climax, the melody emerging from desperate pain into great but complex hope, these towering concrete omens of Hong Kong’s future popped into the frame, glowing brightly in the dark blue sky: Toshiba, Conrad Hilton, Citibank.

The celebrations began. In Lan Kwai Fong, where Hong Kong’s international residents met to party, an expat of European descent with an English accent was talking to the news cameras. She wore a wide-brimmed hat of charcoal gauze. Men in baggy, brightly coloured shirts chugged Carlsberg on the pavements behind her. She did not want to leave. ‘Darling, I’m Chinese. I have my eyes fixed every year,’ she joked to the producer, holding her hands up beside her face. Her fingertips were pointed at her lower brow as if she were about to pull her skin back in order to narrow her eyes.9

Opinion polls showed that there were fears among Hong Kong’s Chinese-majority population regarding the territory’s political future under the rule of Beijing. However, most were pretty optimistic about the handover of the territory, or said that they did not care.10

In the vast hall of a convention centre, dignitaries sat watching the long ceremony. Its climax was marked by a ritual that had been repeated many times since India had become the first British colony to reclaim its independence. One set of flags was exchanged for another, and for Charles, this was the pinnacle of humiliations. ‘At the end of this awful Soviet-style display we had to watch the Chinese soldiers goose step on to the stage and haul down the Union Jack … The ultimate horror was the artificial wind which made the flags flutter enticingly.’ The last notes of ‘God Save the Queen’ rang out from the band of the Scots Guards, dressed in scarlet and topped by their voluminous bearskin hats. The guards’ cymbals had only just hissed out their last trembling note when a Chinese military band struck up the ‘March of the Volunteers’ and the Chinese flag was raised alongside the new flag of Hong Kong.11

Sitting in the audience, Tony Blair also found the Chinese triumphalism of the final handover somewhat humiliating,12 but the ‘tug’ that he felt was ‘not of regret but of nostalgia for the old British Union’.13 Indeed, two months later he was arguing, albeit to the president of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe, that Britain was no longer defined by its colonial past; it was simply something that Britons read about in their history books.14 During the ceremony, foreign secretary Robin Cook had been spied standing around looking relaxed, his hands in his pockets,15 and Charles recognized the same unconcerned attitude in Blair, complaining in his diary that the prime minister was on the island for only fourteen hours (it was more like twelve). As China’s premier Jiang Zemin remarked to Blair, the Labour Party was not burdened by ideological ties to Britain’s colonial past.16 The empire was, in the prime minister’s mind, simply outmoded. Blair later wrote, ‘In the end, however benign we were, they prefer to run themselves and make their own mistakes.’17

He wanted to apply the same principle, albeit to a different extent, to Northern Ireland. With Labour in power and Mo Mowlam in the Northern Ireland Office, the peace process in the six counties of the north was now being led by a Westminster government which the republican and Irish nationalist movement still distrusted, but less intensely. Two and a half weeks after Hong Kong was returned to China, years of work in Belfast, Dublin and London paid off, and the IRA declared a ceasefire. A month and a half later, its political wing, Sinn Féin, announced its opposition to violent tactics, and entered formal talks. In less than a year, the Good Friday Agreement would devolve political power to Northern Ireland and lead the way to the gradual demilitarization of a territory that was part of the UK, but which many of its inhabitants identified as a colonial province occupied by the British. The empire really was disintegrating.

Few people elsewhere in Britain appeared to care much at all, beyond either watching the spectacle of Patten crying and Chinese guards goose-stepping, or feeling that the already dim prospect of an IRA bombing was even more distant. One newspaper columnist reported, after the Hong Kong handover, that ‘there is very little sense of loss in Britain’.18 Northern Ireland felt similarly alien to most people in the UK, and Good Friday passed, in their minds, as a news story of modest significance.

After fifty years of decolonization, and decades of the Troubles, Britain’s imperial story no longer appeared romantic or glorious, even to those who ignored the violence and racism that ran through that history. Many people felt an uncertain mixture of limited shame about this past, nostalgia for its glories and relief that the disputes over Hong Kong and Northern Ireland seemed to have disappeared.

Britain’s elite was divided on the questions of what this confusion was, how to clear it, and who should benefit from that clarification. Charles, like many conservatives, thought this was a problem of national culture. He wrote of Blair: ‘He understands only too well the identity problem that Britain has with the loss of an empire.’ Blair’s left-wing backbenchers would have had another view: the imperium of global markets was, indeed, disrupting elderly established empires and identities, and the meaning these had given to some people’s lives had to be replaced with something more inclusive and egalitarian. The prime...

Table of contents

- Cover

- About the Author

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: You say you want a revolution

- 1. New Labour, new Britain

- 2. Murderers

- 3. The People’s Princess

- 4. Girl power

- 5. Sensationalism

- 6. Cocaine supernova

- 7. Systemic risks

- Conclusion: Crisis

- Notes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access 1997 by Richard Power Sayeed in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.