![]()

1. What is Feminism?

Where are we today?

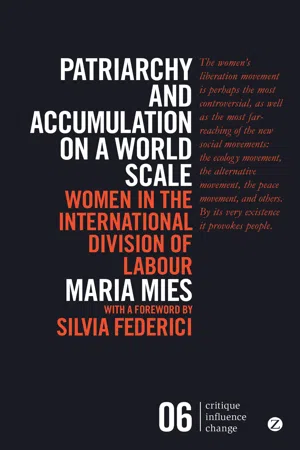

The Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM) is perhaps the most controversial, as well as the most far-reaching of the new social movements: the ecology movement, the alternative movement, the peace movement, and others. By its very existence it provokes people. Whereas one can lead a dispassionate intellectual or political discourse on the ‘ecology question’, the ‘peace issue’, the issue of Third World dependency, the ‘woman question’ invariably leads to highly emotional reactions from men, and from many women. It is a sensitive issue for each person. The reason for this is that the women’s movement does not address its demands mainly to some external agency or enemy, such as the state, the capitalists, as the other movements do, but addresses itself to people in their most intimate human relations, the relationship between women and men, with a view to changing these relations. Therefore, the battle is not between particular groups with common interests or political goals and some external enemy, but takes place within women and men and between women and men. Every person is forced, sooner or later, to take sides. And taking sides means that something within ourselves gets torn apart, that what we thought was our identity disintegrates and has to be created anew. This is a painful process. Most men and women try to avoid it because they fear that if they allow themselves to become aware of the true nature of the man-woman relationship in our societies, the last island of peace, of harmony in the cold brutal world of money-making, power games and greed will be destroyed. Moreover, if they allow this issue to enter their consciousness, they will have to admit that they themselves, women and men, are not only victims, on the one side (women), and villains (men), on the other, but that they are also accomplices in the system of exploitation and oppression that binds women and men together. And that, if they want to come to a truly free human relationship, they will have to give up their complicity. This is not only so for men whose privileges are based on this system, but also for women whose material existence is often bound up with it.

Feminists are those who dare to break the conspiracy of silence about the oppressive, unequal man-woman relationship and who want to change it. But speaking up about this system of male dominance, giving it certain names like ‘sexism’ or ‘patriarchy’, has not reduced the ambivalence mentioned above, but rather intensified and broadened it.

There have been contradictory responses to the new women’s movement right from its beginning at the end of the sixties. The women who came together in this movement in the USA and in Europe began to call themselves feminists and to set up all-women’s groups in which they, for the first time, after the petering out of the old women’s movement in the twenties, began to talk about the ‘problem without a name’ (Friedan 1968). Each of us had listened, time and again in private conversations, to one of our sisters telling us how badly they had been treated by fathers, husbands, boy-friends. But this was always considered the private bad luck of this or that woman. The early consciousness-raising groups, the speaking-out sessions, the all-women’s meetings, the first spectacular actions of women who began to separate themselves from the mixed groups and organizations were all occasions where women could discover that their apparently unique personal problem was the problem of all women, was indeed a social and political problem. When the slogan, ‘The personal is political’ was coined, the taboo was broken that surrounded the ‘holy family’ and its sanctum sanctorum: the bedroom and the sexual experiences of women. All women were overwhelmed by the extent and depth of sexism that came to the surface in these speaking-out sessions. The new concern that arose, the commitment to fight against male dominance, against all humiliation and ill-treatment of women, and against continuing inequality of the sexes created a new feeling of sisterhood among women which was an enormous source of strength, enthusiasm and euphoria in the beginning. This feeling of sisterhood was based on a more or less clear awareness that all women, irrespective of class, race, nation, had a common problem and this was: ‘how men treat us badly’, as the women of the ‘Sistren Theatre Collective’ in Jamaica put it in 1977 when they were about to start their group in Kingston.1

And wherever women come together to speak up about these most intimate and often taboo experiences, the same feelings of indignation, concern and sisterly solidarity can be observed. This is also true for the women’s groups emerging in underdeveloped countries.2 In the beginning of the movement, the hostile or contemptuous reactions from large sections of the male population, particularly those who had some influence on public opinion, like journalists and media people, only reinforced the feelings of sisterhood among the feminists who became increasingly convinced that feminist separatism was the only way to create some space for women within the overall structures of male-dominated society. But the more the feminist movement spread, the more clearly it demarcated its areas as all-women areas where men were out of bounds, the more were the negative or openly hostile reactions to this movement. Feminism became a bad word for many men and women.

In underdeveloped countries, this word was mostly used with the pejorative attribute ‘Western’, or sometimes ‘bourgeois’ to denote that feminism belongs to the same category as colonialism and/or capitalist class rule, and that Third World women have no need for this movement. At many international conferences I could observe a kind of ritual taking place, particularly after the United Nations Women’s Conference in Mexico in 1975. When women spoke from a public platform, they first had to disassociate themselves from ‘those feminists’ before they could speak as a woman. ‘Feminists’ were always the ‘other women’, the ‘bad women’, the ‘women who go too far’, ‘women who hate men’, something like modern witches with whom a respectable woman did not want to be associated. Women from Asia, Latin America and Africa, particularly those connected with development bureaucracies or the UN, usually set themselves apart from those ‘Western feminists’ because, according to them, feminism would sidetrack the issue of poverty and development, the most burning questions in their countries. Others felt that feminists would split the unity of the working class or of other oppressed classes, that they forgot the broader issue of revolution by putting the issue of women’s liberation before the issue of class struggle or national liberation struggle. The hostility against feminism was particularly strong among the organizations of the orthodox left, and more among men than among women.3

But in spite of these negative pronouncements about feminism in general, and ‘Western feminism’ in particular, the ‘woman question’ was again on the agenda of history and could not be pushed aside again. The International Women’s Conference in Mexico, in a kind of forward strategy in its World Plan of Action, tried to channel all the subdued anger and slow rebellion of women into the manageable paths of governmental policies, and particularly to protect the Third World women from the infectious disease of ‘Western feminism’. But the strategy had the opposite effect. The reports which had been prepared for this conference were, in several cases, the first official documents about the growing inequality between men and women (cf. Government of India, 1974). They gave weight and legitimacy to the small feminist groups which began to emerge in Third World countries around this time. At the Mid-Decade International Women’s Conference in Copenhagen in 1980, it was admitted that the situation of women world-wide had not improved but rather deteriorated. But what had grown in the meantime were the awareness, the militancy and the organizational networks among Third World women. In spite of a lot of Third World criticism of ‘Western feminism’ at this conference, it still marked a change in the attitude towards the ‘woman question’. After the conference, the word ‘feminism’ was no longer avoided by Third World women in their discussions and writings. In 1979, at an international workshop in Bangkok, Third World and First World women had already worked out a kind of common understanding of what ‘feminist ideology’ was; and the common goals of feminism are spelt out in the workshop documentation entitled Developing Strategies for the Future: Feminist Perspectives (New York, 1980). In 1981, the first feminist conference of Latin American women took place in Bogota.4 In many countries of Asia, Latin America and Africa, small women’s groups emerged who openly called themselves ‘feminists’, although they still had to face a lot of criticism from all sides.5 It seems that when Third World women begin to fight against some of the crudest manifestations of the oppressive man-woman relation, like dowry-killings and rape in India, or sex-tourism in Thailand, or clitoridectomy in Africa, or the various forms of machismo in Latin America, they cannot avoid coming to the same point where the Western feminist movement started, namely the deeply exploitative and oppressive man-woman relation, supported by direct and structural violence which is interwoven with all other social relations, including the present international division of labour.

This genuine grassroots movement of Third World feminists followed similar organizational principles as that of the Western feminists. Small, autonomous women’s groups or centres were formed, either around particular issues or, more generally, as points where women could meet, speak out, discuss their problems, reflect and act together. Thus, in Kingston, Jamaica, the theatre-collective Sistren mentioned above, formed itself as an all-women group with the aim to raise the consciousness of poor women, mainly about exploitative men-women and class relations. In Lima, Peru, the group Flora Tristan was one of the first feminist centres in Latin America (Vargas, 1981). In India a number of feminist groups and centres were formed in the big cities. The most well-known of them are the Stri Sangharsh group (now dissolved), and Saheli in Delhi. The erstwhile Feminist Network (now dissolved), the Stree Mukti Sangathna, the Forum against Oppression of Women, the Women’s Centre in Bombay, the Stri Shakti Sangathana in Hyderabad, Vimochana in Bangalore, the Women’s Centre in Calcutta. Around the same time, the first genuinely feminist magazines appeared in Third World countries. One of the earliest ones is Manushi, published by a women’s collective in Delhi. In Sri Lanka the Voice of Women appeared around the same time. Similar magazines were published in Latin America.6

Parallel to this rise of Third World feminism from ‘below’ and at the grassroots level was the movement from ‘above’, which focussed mainly on women’s role in development, on women’s studies and the status of women. It originated, to a large extent, in national and international bureaucracies, development organizations, UN organizations where concerned women, or even feminists, tried to use the financial and organizational resources of these bureaucracies for the furthering of the women’s cause. In this, certain US organizations, like the Ford Foundation, played a particularly important role. The Ford Foundation contributed generously to the setting up of women’s studies and research in Third World countries, particularly in the Caribbean, in Africa (Tanzania) and in India. Research centres were created and policies were formulated with the aim of introducing women’s studies into the syllabi of the social sciences.

In India, a National Association of Women’s Studies was formed which has already held two national conferences. A similar organization is at present being formed in the Caribbean. But whereas the Indian association still sticks to the more general term ‘women’s studies’, the Caribbean one calls itself ‘Caribbean Association for Feminist Research and Action’ (CAFRA).

This designation is already an expression of the theoretical and political discussions that are taking place in Third World countries between the two streams – the one from below and the one from above – of the new women’s movement. The more the movement expands quantitatively, the more it is accepted by institutions of the establishment, the more money is coming forward from international funding agencies as well as from local governments, the more acutely the conflicts are felt between those who only want to ‘add’ the ‘women’s component’ to the existing institutions and systems and those who struggle for a radical transformation of patriarchal society.

This conflict is also present in the numerous economic projects for poor rural and urban women, set up and financed by a host of development agencies, governmental as well as non-governmental ones, local and foreign ones. Increasingly, the development planners are including the ‘women component’ into their strategies. With all reservations regarding the true motives behind these policies (see chapter 4), we can observe that even these projects contribute to the process of increasing numbers of women becoming conscious of the ‘woman’s question’. They also contribute to the political and theoretical controversy about feminism.

If we today try to assess the situation of the international women’s movement we can observe the following:

1. Since the beginning of the movement there has been a fast and still growing expansion of awareness among women about women’s oppression and exploitation. This movement is growing faster at present in Third World countries than in First World countries where, for reasons to be analysed presently, the movement appears to be at a low ebb.

2. In spite of their commonality regarding the basic problem of ‘how men treat us badly’, there are many divisions among women. Third World women are divided from First World women, urban women are divided from rural women, women activists are divided from women researchers, housewives are divided from employed women.

Apart from these objective divisions, based on the various structural divisions of labour under international capitalist patriarchy, there are also numerous ideological divisions, stemming from the political orientation of individual women or women’s collectives. Thus, there are divisions and conflicts between women whose main loyalty is still with the traditional left and those who are criticizing this left for its blindness regarding the woman question. There are also divisions among feminists themselves, stemming from the differences in the analysis of the core of the problem and the strategies to be followed to solve it.

3. These divisions can be found not only between different sets of women, separated along the lines of class, nation and race but also within sets of women who belong to the same race, class or nation. In the Western feminist movement the division between lesbian and heterosexual women played an important role in the development of the movement.

4. As each woman joining the movement has to integrate in herself the existential experience of a basic commonality of women living under patriarchy with the equally existential experiences of being different from other women, the movement is characterized everywhere by a high degree of tension, of emotional energy being spent on women’s solidarity as well as on setting oneself apart from other women. This is true for First and Third World movements, at least those which are not under the directives of a party, but are organizing themselves autonomously around issues, campaigns and projects.

5. Many women react to this experience of being both united and divided with moralistic attitudes. They either accuse the ‘other women’ of paternalistic or even patriarchal behaviour, or – if they are the accused – respond with guilt feelings and a kind of rhetorical breast-beating.

The latter can be observed particularly with regard to the relationship between sex and race, which has in recent years emerged as one of the most sensitive areas in the women’s movement in the USA, England and Holland where large numbers of Third World women live who have joined the feminist movement (Bandarage, 1983). In the beginning, white feminists were often either indifferent to the race problem or they took a maternalistic or paternalistic attitude towards women of colour, trying to bring them into the feminist movement. Only when black and brown women began to extend the principle of autonomous organization to their own group, and formed their separate black women’s collectives, magazines and centres the white feminists began to see that ‘sisterhood’ was not yet achieved if one put men on one side and women on the other. Yet although most white feminists would today admit that feminism cannot achieve its goal unless racism is abolished, the efforts to understand the relationship between sexual and racial exploitation and oppression remain usually at the individual level, where the individual woman does some soul-searching to discover and punish the ‘racist’ in herself.

On the other hand, neither do the analyses of black women go much further than to give expression to the feelings of anger of black women who refuse to be a ‘bridge to everyone’ (Rushin, 1981).

There are, as yet, not many historical and political-economic analyses of the interrelation between racism and sexism under capitalist patriarchy. Following the general ahistorical trend in social science research, racial discrimination is put on the same level as sexual discrimination. Both appear to be bound up with biological givens: sex and skin colour. But whereas many feminists reject biological reductionism with regard to sex-relations and insist on the social and historical roots of women’s exploitation and oppression, with regard to race relations, the past and ongoing history of colonialism and of capitalist plunder and exploitation of the black world by white man is mostly forgotten. Instead, ‘cultural differences’ between Western and non-Western women are heavily emphasized. Today this colonial relation is upheld by the international division of labour....