![]()

China’s President Hu Jintao will hand over at least two of his positions, namely those of Party General Secretary and President of China to Xi Jinping at the 18th Party Congress scheduled to be held in early November 2012. Though Hu’s tenure has been dogged by comments that he is not as powerful as his predecessors, his career path shows otherwise. It is likely that Hu Jintao’s influence will, in fact, continue to linger well after he steps down from office.

By the end of 2004, Hu Jintao became the most powerful individual in China, combining the posts of General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Central Committee (CC) (November 2002), President of the People’s Republic of China (March 2003) and Chairman of the Military Commission (September 2004). His elevation to this unrivalled position provided a substantive boost to China’s ongoing military modernization effort. Hu Jintao’s re-election as Party Chief in October 2007 and as China’s President and Chairman of the Military Commission in March 2008, ensured continuation of the military’s modernization and refinement of its operational capabilities in accordance with its evolving doctrine. It also allowed Hu Jintao, as head of the country’s foreign policy formulation establishment and armed forces, to combine the strengths of both and craft a foreign policy designed to advance China’s national interests. In a bold initiative reflecting China’s confidence in its economic strength and armed forces, Hu Jintao in late 2008 deliberately discarded Deng Xiaoping’s advice of ‘taoguang yanghui’, or ‘lie low, conceal capabilities and bide time’, and steered an assertive China on to the world stage.

Hu Jintao, a quintessential Party apparatchik and technocrat, was earmarked for rapid elevation fairly early in his career. While Party elders generally assessed him as politically correct, intelligent, dynamic, loyal and articulate, Hu Jintao actually received crucial breaks because of the support of his mentor Song Ping, a veteran cadre associated with the Ya’nan Central Party School, who steered career-building opportunities his way. Hu Jintao’s close association with Song Ping and possible association with Chen Yun, together with exposure to China’s poorer provinces, impressed on him the positive aspects of central planning and inclusive economic reforms, which he applied later. Hu Jintao’s family background – he was the son of an educated tea merchant of Shanghai – would have given him access as a youth to the fringes of the city’s elite.

Hu Jintao’s mentor, Song Ping, ensured that Hu Jintao switched to the fast-track and, in a far-sighted move, arranged for him when he was Deputy Director of the Gansu Ministry of Construction, to go to Beijing in 1981 along with Deng Xiaoping’s daughter, Deng Nan, for training at the Central Party School. Later, in 1982 he manoeuvred to have Hu Jintao elected as alternate member of the Party’s 12th Central Committee. Hu, at 39 years of age, became the youngest member of the Central Committee and that too when he was only a Deputy Head of a provincial organization, namely the Gansu Provincial Communist Youth League. This major break would certainly have fuelled Hu Jintao’s aspirations and, as he moved up the central Party hierarchy he would have become increasingly aware that he lacked a military background or strong linkages to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Hu Jintao’s opportunity to address this lacunae came very soon with his transfer to Beijing and appointment in 1984 as Head of China’s Communist Youth League (CYL), the country’s largest youth organization which continues to be the crucible for potential members and cadres of the Chinese Communist Party. During this tenure he had a minor run in with two ‘princelings’, Chen Haosu, son of PLA Marshal Chen Yi and He Jiawei, son of General He Changgong, both of whom complained against him to their ‘elders’ who conveyed their complaint to CCP CC General Secretary Hu Yaobang. The incident served to remind Hu Jintao of the influence wielded by the Army in China’s power structure. More importantly, it highlighted to him that though he belonged to an educated and relatively well off family and was an alumnus of the prestigious and well-networked Tsinghua University, he was not a ‘princeling’ and needed to cultivate this influential and powerful grouping of China’s power elite.

Hu Jintao’s big opportunity to remedy his lack of influence with the PLA came in December 1988 when he was appointed Party Secretary for the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR). Already a key assignment, it came in to greater prominence as major riots erupted across Tibet in February 1989, very shortly after Hu Jintao’s appointment. Hu Jintao had moved fast after his appointment to develop ties with the PLA. As the situation became increasingly tense and he apprehended more serious rioting during the anniversary of the Lhasa Uprising in March, Hu Jintao coordinated with the Chengdu Military Region Commander and had almost 17 divisions, or 170,000 PLA troops, deployed in Tibet prior to obtaining approval from the Party Centre. In fact, he had been advised by Party General Secretary Zhao Ziyang to try and avoid using force. When serious rioting erupted on March 3-4, the PLA troops quickly locked down the city and fanned out across Tibet preventing further rioting. By the 10th March, Hu Jintao had the situation in Tibet under control. His bold action in deploying PLA troops without approval of the Party Centre, in reality very unusual for Party apparatchiks who normally prefer to unwaveringly adhere to the line laid down by the Party Centre, was noticed by Deng Xiaoping who promptly earmarked Hu Jintao for important higher appointments.

By the 14th Party Congress in 1992, Hu Jintao had been elevated to the 7-member Politburo Standing Committee, the highest decision and policy making body of the CCP, ignoring the claims of many others senior to him. More significantly, Hu Jintao was given charge of the all-important personnel and propaganda portfolios which ensured that he was privy to the records of all senior officials of the Party, Government and PLA and had a major input in their career progression. This helped Hu Jintao cultivate PLA officers with promise and, probably, do a select few some favours. From 1993-2002, Hu Jintao was Head of the Central Party School, which is the training base for all Party cadres in the Party, Government and Army, who have been earmarked for further promotions. This appointment broadened his opportunities for contact with upward mobile Party and military cadres.

Once Hu Jintao took over as General Secretary of the Party in 2002, he began expanding his influence in the Army through the Party and began inducting his supporters into the Party Central Committee. In a departure from past practice, Hu Jintao ensured the election of a large number of persons – 94 percent – among the 65 PLA representatives in the CCP CC. Of them around 60 percent were later elevated to higher military rank between 2005 and 2007 when Hu Jintao was Military Commission Chairman, thus confirming patronage links.

His position was strengthened once he was appointed Vice Chairman of the Central and Party Military Commissions (both have identical membership and are generally referred to as Central Military Commission) in September 1999. Unlike previous civilian appointees to the position of Central Military Commission Vice Chairman, Hu Jintao took active interest in the PLA and the military reforms initiated by Jiang Zemin to divest the Army of its business ventures. Hu Jintao continued to expand his influence in the PLA and soon demonstrated this in September 2004 when the time came for Jiang Zemin to retire from the post of Chairman of the Central Military Commission. Informed speculation was rife in the months preceding the 4th plenary session of the 16th Central Committee of the CCP (16-19 September 2004) that Jiang Zemin was reluctant to step down. However, Hu Jintao had adequate support in the Politburo and among the Party ‘elders’ who strongly suggested to Jiang Zemin that he retire fully. An important demonstration of Hu Jintao’s confidence were his remarks at the centenary birth anniversary celebrations of Deng Xiaoping. On this occasion Hu Jintao pointed out in his speech that Deng Xiaoping had stepped down from his posts two years before he had to, thereby indicating that he reposed confidence in the successor. Meanwhile, in a clear demonstration of Hu Jintao’s influence in the PLA, PLA Commanders separately complained of confusion in the PLA’s chain of command because of the existence of two centres of power. Jiang Zemin was left with little alternative but to step down and Hu Jintao took over as Chairman of the Central Military Commission. Hu Jintao’s victory was complete, in that Vice Premier Zeng Qinghong, who was Jiang Zemin’s favourite, was not appointed to the Central Military Commission as Vice Chairman. Promptly on taking over as Chairman of the Central Military Commission, Hu Jintao reiterated his interest in the PLA’s modernization programme and particularly its doctrine of Integrated Joint Operations. He expanded the Central Military Commission and, for the first time ever, included the Commanders of the PLA Air Force (PLAAF), PLA Navy (PLAN) and Second Artillery as members.

Hu Jintao accorded priority to ensuring the PLA’s ‘absolute loyalty’ and ‘absolute obedience’ to the CCP at a time when economic reform policies were causing instability in Chinese society. This was important for him to personally tighten his grip on the PLA. He also had a long-range objective since the succeeding generations of leaders would increasingly be CCP cadres with no experience of the Army or, in many cases, with few linkages. He initiated a series of measures to ensure the PLA’s ‘absolute’ loyalty. Successive ‘study sessions’ and ‘education’ campaigns were launched throughout the PLA emphasizing that the CCP led the PLA and that the PLA must always be ‘absolutely obedient’ to the Party Centre. Distinction was made between the PLA and armies of other countries by pointing out that the PLA was the guarantor of ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ and was a ‘people’s army’ unlike those of other nations. The Communist Youth League (CYL) and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were directed to launch recruitment drives throughout the PLA to increase membership in the PLA. The PLA’s General Political Department was strengthened and Political Commissars were given a greater say in the promotion of officers. Political Commissars also began being rotated within the PLA, PLAAF, PLAN and Second Artillery and posted to different operational commands to provide them all-round experience.

Hu Jintao has contributed a lot to the modernization of the PLA and initiated concrete measures to ensure that the PLA develops its capability to fight modern wars as per its revised doctrine. He reinforced Jiang Zemin’s policy of placing Defence on the same footing as the other Modernisations and ensured double-digit budget hikes for defence. He took forward the doctrine of fighting hi-intensity, hi-tech local wars envisaging integrated joint operations. To facilitate the latter, Hu Jintao expanded the Central Military Commission, the country’s highest military policy decision making body, in September 2004 when he for the first time ever included the Commanders of the PLAAF, PLAN and Second Artillery as members. The following year he effected a restructuring of the Military Regions, including protocol-wise. They were listed as: Shenyang, Beijing, Lanzhou, Jinan, Nanjing, Guangzhou and Chengdu. More importantly and again in a significant departure from traditionally past practice, Hu Jintao for the first time in 2006 inducted an officer each from the PLAAF and PLAN as Deputy Chief and Assistant Chief respectively of the PLA General Staff. A PLAAF Major General has, at least since 2006, been appointed Deputy Director in the PLA General Staff Department’s First Directorate (Operations).

Integrated joint operations are clearly a high priority with Hu Jintao viewing them as a follow-up to the creation of high-mobility Rapid Reaction Forces in the PLA. Hu Jintao enunciated his policy on national defence on 15 October 2007, when he declared: ‘To strengthen national defence and the armed forces occupies an important place in overall arrangements for the cause of socialism with Chinese characteristics. Bearing in mind the overall strategic interests of national security and development, we must take both economic and national defence development into consideration and make our country prosperous and our armed forces powerful while building a moderately prosperous society in all respects’. The number of integrated joint service exercises conducted by the PLA in the past few years has shown a steady increase. These now involve Group Armies and formations from different Military Regions and services. The exercises envisage complex electromagnetic environments and others include satellite overflights and UAV reccee activities. The exercises reflect the PLA’s effort to develop counter-attack capabilities under these conditions.

Hu Jintao effected a major innovation at the 17th Party Congress (2007) in the Central Military Commission Secretariat. For the first time the Secretariat of the Central Military Commission included no PLA officer. The Secretariat, which is responsible for the agenda, daily roster of events etc. exercises influence on the decisions of the Central Military Commission. By this singular move, Hu Jintao ensured total control over the PLA, the control of the Party over the Army and distanced the PLA from politico-military affairs. No other civilian sits on the Central Military Commission either. The severe earthquake in 2008 that caused devastation in Sichuan demonstrated the extent of Hu Jintao’s grip and control over the PLA. The PLA and People’s Armed Police divisions did not initially fully respond to Premier Wen Jiabao’s presence in Sichuan where he was directing relief operations, but the forces got deployed only once instructions by Hu Jintao were issued. Analysts have seen a parallel in Hu Jintao’s decision to return hastily to Beijing from the G-8 Summit in Italy in July ’09, prompted by the outbreak of rioting by the Uyghurs, with the need for him to personally direct military operations in Xinjiang.

Analysis of the composition of the 17th CC (2007) reveals that Hu Jintao, while moving to induct individuals loyal to him into the CCP CC, did not lose sight of his larger objective of pushing rapidly ahead with modernization of the People’s Liberation Army with the emphasis on fighting and winning a high intensity local war and Integrated Joint Operations. The PLA representatives to the 17th CC included 37 of the most important military leaders including members of the Central Military Commission, the senior leadership in the four General Departments, the four services and the three top military academic institutes. Of these PLA representatives 60 percent were promoted to their current military posts since 2005 and the remaining 40 percent in 2007, in other words during Hu Jintao’s tenure. The Commanders and Political Commissars of all 7 Military Regions were made full members of the 17th CC with 12 of them being appointed to the CC for the first time. Of the 35 top military officers in the 17th CC, 21 entered this body for the first time and of them 20 received their military promotions after 2007, or during Hu Jintao’s tenure as Chairman of the Central Military Commission. Of the 19 officers of the rank of General/Admiral, 10 were granted this rank after Hu Jintao took over from Jiang Zemin as Military Commission Chairman in 2004. Hu Jintao was hampered in his effort to induct loyalists into the CCP CC by the more or less fixed number of PLA representatives in this high-level political body. He, therefore, reshuffled the membership and inducted more representatives from the other services. This move had the effect of giving the PLAAF and PLAN greater exposure to the country’s higher political decision-making bodies. The combined percentage of PLAAF and PLAN officers in the CC doubled from 14 percent in 1992 to 25 percent in 2007. Broken down further, the PLAAF representation increased 200 percent and the PLAN’s 133 percent over the 15-year period ending 2007. This change in composition of the 17th CC from those earlier was of major consequence because it reflected the change in the doctrine of war of the PLA and shift from a defensive posture to a more outward looking posture focused on projecting power offshore. The representation of the PLA ground forces, however, continues to be dominant in the CC though it declined in percentage terms from 83 percent in 1992 to 69 percent in 2007.

The PLA has since the early 1990s followed rigid regulations regarding promotions of officers, which includes the need for them to complete a specified tenure in a rank before promotion to the next. This was a limitation on Hu Jintao’s effort to build a base of loyalists in the PLA. He got around this by elevating his candidates to higher posts without conferring on them the attendant higher rank. In many cases the PLA officers, who were younger than their seniors and had little opportunity of holding important higher level assignments for many years, suddenly found themselves appointed to these posts. Except for the formal military rank, which followed in due course in accordance with military regulations, the newly elevated officers enjoyed all the attendant perquisites and authority of the senior assignment. A number of officers in the PLA were beneficiaries of Hu Jintao’s policy. Examples include the Beijing Military Region (MR) Commander Fang Fenghui, Lanzhou MR Commander Wang Guosheng and Nanjing MR Commander Zhao Keshi. Each of them was a Chief of Staff when promoted and not a Deputy Military Region Commander as they should correctly have been. Similarly, Wang Xibin and Tong Shiping, the new Commandant and Political Commissar respectively of the National Defence University were, prior to their promotion, Chief of Staff of a MR and Assistant Director of the PLA’s General Political Department. The 17th CC also saw the induction of younger officers and 11 of the 65 PLA representatives held the rank of Major General or lower. These were: Cai Yinting, Chief-of-Staff of Nanjing MR; Ai Husheng, Chief-of-Staff of Chengdu MR; Xu Fenlin, Chief-of-Staff of Guangzhou MR and Liu Yuejun, Lanzhou MR Chief-of-Staff. All these officers were Major Generals at the time of their promotion and were in their mid-50s. Other similar elevations/appointments occurred recently in the PLA’s four General Departments. In the General Staff Department the Chief-of-Staff of the Shenyang MR Lt General Hou Shusen was promoted Deputy Chief of General Staff in PLA Headquarters, possibly vice Deputy Chief of the PLA General Staff Department and Commander of the Guangzhou MR General Liu Zhenwu; and Maj General Chen Yong was shifted from the post of Dean of the Nanjing Army Command College and promoted to Assistant Chief-of-Staff for the PLA Headquarters of the General Staff, in place of Maj General Yang Zhiqi who retired. In the General Armaments Department, Maj General Niu Hongguang was elevated as Deputy Director of the General Armaments Department vice Lt General Zhang Jianqi, who was due to retire.

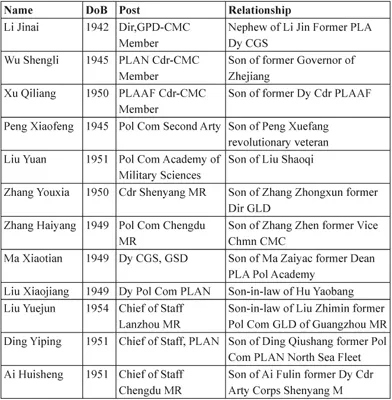

Hu Jintao has carefully nurtured those loyal to him and, conscious of their influence in the Party and Army, began building a support base among the ‘princelings’ (‘taizi’). In late July 2009 he promoted 3 more officers to the rank of General. Included in these were the Deputy Chief of the PLA General Staff and PLA Air Force Major General Ma Xiaotian, who has been in charge of Intelligence in the PLA and been outspoken in his comments regarding the US’ designs in the Asia-Pacific and its defence relationship with Taiwan. He is a ‘princeling’ and assessed to be a loyalist of Hu Jintao. Significantly, the other two promoted to the rank of General are also ‘princelings’. They are Zhang Haiyang, son of a former Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission and Politburo Member, General Zhang Zhen, and Liu Yuan, son of the late Liu Shaoqi at one time Mao Zedong’s designated successor as President of China but who was purged during the Cultural Revolution. Like Ma Xiaotian, Liu Yuan is reputed to be a hardliner on Taiwan. He is credited with replying, to a remark about a possible strike on the Three Gorges Dam by Taiwan, that it would provoke a retaliation that would ‘blot out the sky and cover up the earth’. The remark generated considerable negative comment in the US.

Other ‘princelings’ promoted to the top echelons of the PLA in Hu Jintao’s tenure are Li Jinai, Wu Shengli and Xu Qiliang. All are in the Central Military Commission. There are at least a dozen ‘princelings’ at senior levels in the PLA. Their details are given below.

The other privileged category of individuals in the Chinese Communist Party and PLA are the ‘mishu’, or those who have served as personal assistants to senior PLA or Communist Party cadres. The ‘mishu’, by virtue of their appointment, develop close ties to other senior leaders which helps them in their career progression. Among the current PLA elite at least 8 belong to this category. They include Jia Ting’an, Director of the CMC General Office who was Jiang Zemin’s ‘mishu’ at one time, Cai Yingting, Nanjing MR Chief of Staff who was CMC Vice Chairman Zhang Wannian’s ‘mishu’, and Cao Qing, who used to be Defence Minister Ye Jianying’s bodyguard. The majority of these beneficiaries, all of whom received out-of-turn elevation or promotion during Hu Jintao’s tenure, would owe their loyalty to him while they would, of course, contribute to the PLA with their youth and better education.

The most important and prominent ‘princeling’ who also served for ...