![]()

1/

Back in the States: a glance at foreign exchange

The radio blares from the kitchen: ‘The dollar fell against the yen in heavy Tokyo trading today, closing at 105.75 yen, down two yen from Friday’s close. In early European trading, the dollar is mixed against the euro and the pound.’

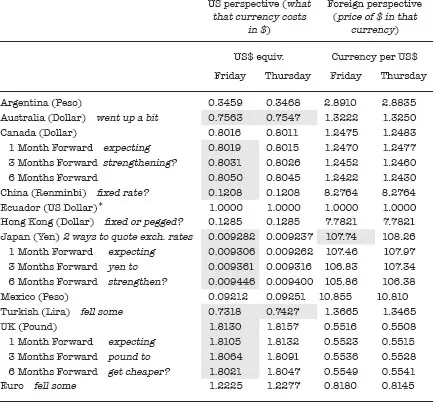

I look at the Wall Street Journal’s website (online.wsj.com) and select ‘currencies’ to pull up a table that lists about sixty foreign currencies from the Argentine peso to the Venezuelan bolivar. I select about a dozen currencies and download them to see what can be learned from this listing (see figure 1.1). I underline the first thing that catches my eye at the top. These must be the wholesale market rates in New York, because these quotes are for trades ‘among banks in amounts of $1 million and more’; the fine print warns ‘retail transactions provide fewer units of foreign currency per dollar.’ So, as the trip to Turkey taught, the money-changing business is like any other. The middleman collects a profit.

The next thing that catches my eye is that for every currency they show two ways of quoting the exchange rate, one they call the ‘US$ Equivalent’ and the other ‘Currency per US$.’ To compute the difference I go down to the Japanese yen, and see that a yen was worth less than a penny on Friday, or about nine-tenths of a cent. So, if I were in Japan and was charged a thousand yen for this breakfast, I would know that the bagel and coffee were costing me a little over 9 bucks. The second way they’re quoting it is from a Japanese point of view, the price of the dollar or how many yen it takes to buy a dollar. From Friday to today, the dollar fell in value from 107.74 yen to 105.75 yen. So for a Japanese tourist visiting New York, a $9 breakfast would have gotten a little less expensive over the weekend, since $9 would convert back into fewer yen on Monday than on Friday.

1.1 / Foreign Exchange Rates

Friday, 3 June 2005 NEW YORK (Dow Jones) – The New York foreign exchange mid-range rates below apply to trading among banks in amounts of $1 million and more, as quoted at 4 p.m. Eastern time by Reuters and other sources. Retail transactions provide fewer units of foreign currency per dollar.

* Adopted U.S. dollar as of 9/11/00.

Source: Reuters, as reported in Wall Street Journal, 6 June 2005.

I see that the yen is like the UK pound and most of the other currencies listed; their values fluctuate from one day to the next. Two exceptions appear to be the Hong Kong dollar and the Chinese renminbi, which at this time look like they might be pegged to the US dollar since they traded at the same values on Thursday and Friday, both of them valued at more than twelve cents. Also, it looks as though on 11 September 2000, Ecuador eliminated its currency and adopted the US dollar.

Also I see the banks are quoting 1-month, 3-month and 6-months forward rates for the Canadian dollar, the British pound, and the Japanese yen, in addition to the rates for the day. I highlight these and note that the pound looks slightly less expensive to buy forward, while the Canadian dollar and the yen look more expensive forward. Are the currency traders predicting the pound will fall a bit, and the yen and Canadian dollar will strengthen against the dollar?

I note the euro fell slightly against the dollar and the Australian dollar rose from Thursday to Friday, so they are floating currencies. And then there’s the Turkish lira, which appears to be falling.

This is about all that can be seen just looking at the table from the Wall Street Journal. There are two ways to express the same exchange rate. Some currencies float against each other; some are fixed. Some move more quickly than others. Some have developed forward markets, others maybe not. Banks are at the center of the currency markets, and there’s a wholesale market for large blocks at a time in New York. Trades between banks are for sizeable amounts, but retail amounts to customers would cost more. But this little snapshot of two days’ worth of foreign exchange trading raises more questions than it answers.

What exactly is being exchanged on the currency markets? Who are the major banks involved in this business? Who are their customers, and how much are they charged? How do customers buy currencies from the banks? How do the banks buy and sell currencies with each other? What makes some currencies float and others stay fixed? What are forward rates about, and why are they higher or lower than current rates?

I thumb through the telephone book and find a nearby bank that has a listing for foreign exchange. I need an introduction, so I call a former student who works there. Alice tells me she’ll call the head of the department. She says the small group of traders are known at the bank for working hard and having a good time. In ten minutes, Alice calls back and gives me the go-ahead to contact the head of the foreign exchange (FX) department.

Mr Roberts says his schedule is filled for the rest of the week, but if I could get there in an hour he’ll be able to work me in for about forty-five minutes. ‘If you’re interested, I’ll introduce you to my people in the trading room, who’ll show you what they do. Bring a photo ID You’ll need it to sign in at the lobby.’

![]()

2/

A visit to a local bank: what do money changers buy and sell?

Mr Roberts tilts back in a leather chair behind a large desk.

‘Have you always had all the security check-points?’ I ask.

‘No, they were put in after September 11th.’ He describes some of the other changes at the bank, which was for most of its history a town bank but in the 1950s expanded to other towns and cities in the state. Then in the 1990s the bank began acquiring banks and opening branches in other states. These acquisitions were done cautiously and turned out to be profitable. ‘Now we’re a target for a takeover, if we don’t successfully negotiate this merger.’

A senior vice-president and head of the foreign exchange department, Mr Roberts has worked for the bank for more than thirty years, most of that time in foreign exchange. He describes what it was like under fixed exchange rates. ‘Back when I started, foreign exchange was a no-brainer, but in 1972, when Bretton Woods1 broke down,’ Mr Roberts’s blue eyes light up, ‘we had to mobilize. There hasn’t been a dull moment since.’

‘How has your currency business evolved over this time?’

‘Our foreign exchange operations have always been simply an extension of corporate banking services we offer customers.’ Before the expansion into other states, he served the customer base with a staff of four; prior to that he and two women ran the show; and it began with him and one clerk. ‘The entire time we had a very high profit-to-expenses ratio. Then we acquired a bank in another state that had a foreign exchange department with fifteen people. They did a larger volume business but with a much lower profit-to-expenses ratio.’

‘Did the acquired bank keep its foreign exchange department after the merger?’

‘No.’ He explains that the costs of outfitting a state-of-the-art trading room are high, and to cut down on staffing and other duplications, they decided to centralize their operations at company headquarters here. ‘We kept the “niche” business. We offer competitive rates and a highly personalized service to our corporate customers, and we’ve combined it with a moderate dealing business.’ He says proudly, ‘We’re doing all this with a staff of only ten people, including me.’

‘And with a merger in the works?’ I ask.

‘Depending on who gets us. The bidders are much larger than we are. One has a trading room with three hundred stations, sixty of them devoted to foreign exchange, the rest to stocks, fixed-income securities, and money market instruments. Our department – though highly profitable – will soon be dissolved. Of course, I’m retiring before that happens.’ Melancholy crosses his face.

I decide to shift to a happier past. ‘Why, for the last few decades, have companies chosen to do business with you instead of going through a big New York bank?’

He brightens. ‘First, they know they won’t get a better deal with the big guys. Second, most of our customers already use us for cash management and payrolls. We know them and their creditworthiness, and they know us. They realize our account executives will spend just as much time on a $20,000 transaction as they would for a $20 million one. That doesn’t happen in New York. Several years ago, we were attracting accounts from some of the big New York banks.’

‘How did you do that?’

‘It became known that we separated our corporate service section, which carries out orders for customers, and our dealer section, which trades to make profits for the bank.’ He says that back then the typical New York account executive also made money from dealing – a conflict of interest in his view. ‘You’ll see in the trading room that we keep the two positions – account executive and dealer – separate, so our account executives work for the customer and try to get as good a price as possible from our dealers. The big banks saw this and copied us.’

‘Mr Roberts, you’ve worked in this business for more than thirty years and know it inside and out. I’ve got some beginner questions for you if you don’t mind. First of all, when I think of currencies being traded, I picture myself in a foreign land, at the airport or train station, changing my $20 bills for their money.’

Mr Roberts smiles. ‘That’s the picture most people have.’

‘How relevant is this picture for today’s world?’

‘It’s just the retail fringe.’ He says that direct exchange of notes happens in every country, especially around tourist attractions. In Eastern Europe and developing countries, where there is little faith in the banking system, it takes on a more important role. He recalls a customer who did business in Russia. ‘Before leaving, he would come in and get stacks of $100 bills. His man in St Petersburg would use the money for investment deals.’ He explains that the center of the currency markets, where wholesale rates are set, bank account money is traded, not physical units of currency. ‘Everyone else who trades in those currencies, even the money changer at the airport, watches these wholesale rates and adjusts buy and sell rates according to the wholesale changes at the center of the currency market.’

‘How might the image of physical currency changing hands be misleading about the actual workings of currency markets?’ I ask.

‘People get confused by this all the time.’ He explains that when physical currency is traded, there is an exchange of money from one country to the next. When bank account money is traded, it doesn’t cross a border. ‘It just moves between accounts inside the two banking systems.’

‘Can you give an example?’

‘Well, let’s say I buy Swiss francs with dollars. On delivery day, funds from my dollar account in the US are sent to their dollar account in the US, and they’ll send Swiss francs from their account to ours at a correspondent bank in Switzerland. Then they can make dollar payments and we can make Swiss franc payments.’

‘When you say “send,” do you mean you write them a check?’

‘No. The funds are wired – electronically sent. Only the tiniest fraction of foreign exchange involves the trade of physical currencies, and practically none of the delivery instructions are made through checks.’

‘You mentioned “on delivery day.” Is there a gap between when you agree to trade a currency and when the funds are finally delivered?’

‘There are two gaps: When and where.’

I ask him to explain, and he says that only with physical currency are there no gaps. You show how many dollars you want to change, the money changer writes down an amount of local currency you will get, you pass your dollars through the window and the money changer passes the local currency back. ‘The deal and the delivery are in the same place at the same time.’

’And when the deal involves account money?’ ‘Account money deals can be struck anywhere.’ He gives the example of someone in Timbuktu agreeing to trade US dollars for British pounds with someone in Machu Picchu. All they need is a secure communications line and assurance that the other will actually deliver the funds. After the deal is ...