![]()

1 | Employment opportunities for women in Europe

NICKY LE FEUVRE AND MURIEL ANDRIOCCI

We have prepared this chapter with the aim of providing a basic framework for understanding the employment opportunities for Women’s Studies graduates in nine European countries (partners in the EWSI project – see Introduction to this volume). We thus take a systematic look at the national variations in women’s labour market participation generally. The project was based on the idea that, due to the particular training they receive, Women’s Studies graduates are in a better position to contest the gender stereotypes that shape women’s experiences of the work–life interface than are most other women of their generation. In order to verify this hypothesis, we thought it important to provide some knowledge about the dominant ‘gender order’ (Connell 1987) or ‘sexual contract’ (Pateman 1988) that characterizes the different European Union (EU) member-states at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

We therefore briefly propose a theoretical framework for understanding the potential influence of Women’s Studies on women’s employment expectations, aspirations and experiences, before going on to present a general statistical overview of women’s employment rates and patterns in the partner countries of the EWSI project. With reference to the recent research on gender and welfare states, we attempt to illustrate the dynamic nature of society-specific gender relations, in relation to women’s labour-force participation, to the domestic division of labour and caring, and to public policy decisions. As many authors have stressed, these three dimensions of gender relations have all been contested and transformed in recent years. Since the second wave women’s movement has played an important role in redefining the relative positions of men and women in employment and in the family, and in encouraging equal opportunity public policy innovations, and since the knowledge-base for Women’s Studies was inspired by the women’s movement, it seems logical to conclude that Women’s Studies training provides students with the ability to negotiate the terms of existing gender relations. Women’s Studies training not only provides students with detailed knowledge of the social processes that produce gender discrimination and inequality, it also enhances their self-confidence and ability to negotiate more egalitarian relationships in their daily lives. In the third part of this chapter, we discuss the potential impact of Women’s Studies training on women’s employment patterns in the EU and conclude with an analysis of the potential role of Women’s Studies for improving the efficiency of European and national equal opportunities measures in the future.

Theoretical perspectives on women’s employment in Europe

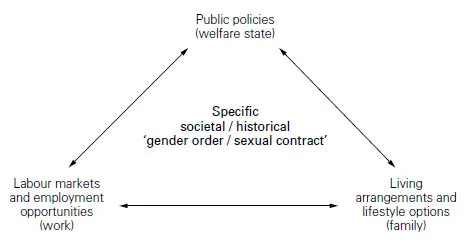

In the EWSI project we decided to adopt the ‘gendered welfare states’ analytical framework developed throughout the 1990s by several European researchers. This approach was particularly relevant for our project, since it places the question of women’s employment in a global societal context. It suggests that three dimensions of contemporary European societies, which traditional academic disciplinary boundaries have all too often dissociated, need to be analysed together: first, the process of industrialization and the specific labour market characteristics of industrial and post-industrial societies; second, the family sphere, seen both from the angle of marriage and parenting, and from the angle of the domestic, educational and ‘caring’ activities carried out there; and, lastly, the state, or rather the public policies which have historically shaped the relationship between the two above-mentioned spheres, and which are also liable to determine the precise forms of this relationship in a given national context, in particular as regards the social positions and roles collectively attributed to men and women (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 is useful for a comparative analysis of the employment aspirations and opportunities of graduates in Women’s Studies, since it relates simultaneously to the social structures that characterize a society at a given time in its history and to the collective representations which constitute the ‘mental aspect’ of gender relations (Godelier 1984; Guillaumin 1992). We can thus understand not only why job opportunities, for women in general and for Women’s Studies graduates in particular, are not identical in all European societies, but also why women’s employment aspirations and experiences also vary according to their societal and historic context. Thus: ‘State policies can affect, notably, women’s demands for employment, the way in which women define themselves as active or inactive within the labour market, the costs and profits generated by the decision to take up paid work, given the costs of child care and other constraints’ (European Commission 1996b: 2).

Women’s employment and welfare state regimes Although academic feminist research has always been interested in the role of the state in maintaining or combating gender inequalities in the labour market, the debate on European comparisons of women’s employment patterns was refuelled in the early 1990s by Gosta Esping-Andersen’s (1990) The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Esping-Andersen was not directly interested in the question of gender relations, and was to be severely criticized by a wide range of feminist scholars for his neglect of this question (Daly and Lewis 2000; Jenson 1986; Lewis 1992; Sainsbury 1994, 2001; Ungerson 1990). This book can nevertheless be seen as a major milestone in attempts to analyse the role of the state in shaping women’s employment in contemporary western societies. With the explicit aim of analysing the potential for ‘convergence’ between the different ‘welfare regimes’ of the EU member-states, Esping-Andersen’s work was an extension of the previously available frameworks for analysing the role of the state in contemporary western (capitalist) societies (Titmuss 1963, 1974).

Figure 1.1 Societal structures and the gender contract

The question of the dynamic nature of these societal models is at the heart of the feminist Birgit Pfau-Effinger’s work. According to Pfau-Effinger, the new ‘gendered welfare state regime’ models need to be refined, notably in order to account for changes over time. Through a comparative analysis of the ‘modernization of motherhood’, Pfau-Effinger claims that women’s employment patterns are not solely determined by state intervention in the labour market and childcare provision. In order better to understand the national and historical variations in women’s employment patterns, all the ‘gendered’ aspects of modern societies need to be analysed. In addition to the ‘gender systems’ highlighted in previous feminist research on welfare state regimes, Pfau-Effinger introduces the notion of ‘gender culture’, which refers to the specific set of standards, norms and values that define gender relations and the sexual division of labour in a particular national and historical context. Thus, men and women do not only live in societies where the objective possibilities for more egalitarian relations between the sexes vary considerably, they also adhere to very different beliefs about the ‘ideal’ nature of men and women’s place in society (Pfau-Effinger 1996). The societal ‘gender arrangement’ must therefore be analysed in a way that accounts for the ‘objective’ social structures and for the ‘subjective’ relationship of individuals to those structures. According to Pfau-Effinger, the nature of the ‘gender contract’ in each country can be identified by means of the following indicators: (a) the fact that men and women are either assigned to ‘specific spheres’ or that both sexes are expected to articulate their professional, their parental and their personal commitments to society; (b) the degree to which equal opportunity measures are institutionalized at all levels of society; (c) the fact that childcare and other forms of care are either primarily assigned to individuals and families, to public sector institutions or to the market; (d) the degree to which heterosexual marriage dominates lifestyle choices, in comparison to alternative living arrangements (single-parent families, staying single with or without children, community-based living arrangements, etc.) (Pfau-Effinger 1993: 390). Pfau-Effinger is particularly interested in the ability of different social groups to impose changes on the dominant social structures and norms in a given social context. Although she does not deny that there may be structural inequalities between the different groups involved in the negotiat...