![]()

CHAPTER 1

The failure of management science

and the US business school model

In this first chapter, as throughout the book, we are not concerned with establishing the truth value of management as “science” in our critiques of managerialism and the new paradigm in US business school education. That discussion we leave to management theoreticians and philosophers of science. Nor are we particularly concerned with the interpretations of historians, politicians, journalists, and social scientists, with various axes to grind, of recent US management events. Instead, we let the historian’s old rule of thumb serve as a guide in our presentation, namely that informed contemporaries who witness events and often participate in them, usually, unless misinformed about or unaware of facts, get the story right the first time around as they live it. Since contemporaries close to events deftly wield Occam’s razor, they best tell the story about the failures of management science and the US business school model, failures which, particularly in the past forty-plus years, surprised and puzzled most Americans in and outside of management, and still do those who are unwilling to suspend disbelief.

The first event of contemporary assessment covered in this chapter is the usefulness of war-spawned operational research techniques in the solving of complex postwar management problems. The chapter then turns to an assessment of a different order. It discusses the inability of Americans equipped with the toolkit of the new paradigm to cope with the greatest challenge US manufacturing faced in the second half of the twentieth century, that coming from Japan. This story is not told in ruined companies and unemployed people (Locke, 1996, 158-75) but in a critique of the epistemology of the new paradigm in management disciplines introduced postwar in the business schools. The seismic shift in consciousness that the epistemological arguments entailed infiltrated discussions about Japanese manufacturing culture. The debates affected the thoughts and lives of many people. The life of one prominent business school professor, H. Thomas Johnson, is used as a reference point to illustrate the change and the resistance to change that occurred, as managerialism and the business schools struggled to preserve their newly established orthodoxy.

The chapter’s last section looks at business schools’ relations with praxis after 1980 when, with the scientific standing of the faculties improved, top business schools had turned into research institutions, with multiplying subdisciplines and proliferating peer-reviewed scientific periodicals. The concluding section weighs contemporary views about how well graduates educated in the reformed business schools performed in the two major events that shaped the US economy in the mid-1980s – the Japanese manufacturing challenge and the industrial revolution in information technology (IT).

The OR experience: the new paradigm in postwar business schools

There were critics right from the beginning of what Locke called “the New Paradigm” (Locke, 1989, Chapter 2) and Schlossman, Sedlak and Wechsler (1987) the “New Look” in business school education. Among them were members of the old descriptive school in economics and business studies who distrusted the mathematicians. Fearful that their models poorly mirrored reality, sure, in any event, that mathematics would make business studies incomprehensible to businessmen, and hence separate them even more from academia, they often put up a spirited resistance (Larsfeld, 1959; Marschal, 1940; Koch, 1960; Mattessich, 1960; Piettre, 1961; Howson, 1978; Hudson, 2010). But it was difficult to defend the point of view of the old pre-mathematics paradigm, since the victory of the new men would make non-mathematically schooled business economists’ views seem academically passé, and their protests self-serving. Besides, the powerful technical arguments of the self-confident purveyors of mathematical omniscience had to have their day. Until more numerate as well as nonnumerate people had experience with the new techniques, a telling body of criticism could not appear. When they did, the doubters began to assemble.

It is easy, therefore, to find maverick critics cavorting outside the citadel of a new discipline while the victory bells are still ringing inside. Doubts, however, crept up within the ranks of operations research scientists themselves. Since the OR experience in the two pioneering OR countries (Britain and America), as noted in the Introduction, somewhat differed because of academic traditions, OR appraisals varied somewhat within OR societies in each country.

There was more of a conflict in Britain between academia and working OR people and, because of the lateness and sluggishness of OR’s academicization, a greater imbalance between the two. It was as if the academic version of OR did not take root in the UK as it did in the United States. That version was dominated by abstract, complex, highly theoretical mathematical models which, because of academic career conventions – publish or perish – captured the scientific OR journals; the American academic version was carried into British OR academia belatedly through contact with Americans. K. B. Haley notes that Russell Ackoff’s arrival at the University of Birmingham, as Joseph Lucas Visiting Professor, in 1961 was the signal event. “His presence had a major impact on the whole of the UK educational scene, inspired a number of initiatives in the way the subject was viewed in industry, and was one of the prime movers in the establishment of the Institute for Operational Research” (Haley, 2002, 85). The University of Birmingham, which had invited Ackoff, had instituted a master’s in OR in 1958; his presence there seemed to stimulate the development of academic OR in the UK, with master’s degrees in OR initiated at Imperial College London and at Cranfield in 1961; while a master’s course in the subject started at the University of Hull in 1962.

The British Journal of the Operational Research Society (JORS) began, under the influence of US OR, to reflect the greater formal scientific attributes of US OR, for, increasingly, the scientific articles in it came from academics employed in American educational institutions. Patrick Rivett’s analysis of the articles published during one twelve-month period observed that “of 103 papers, 81 were by academics of whom only 31 were British. The Journal had over half of the papers in the form of theoretical materials from overseas academics” (Rivett, 1981, 1057). Considering the large size of British OR society membership (Table 1.1), the vast majority of working OR people, that is, the vast majority since the academic operational research group was so small in the UK, did not publish. Rivett claimed that “80% of OR people go through life without publishing anything” (Rivett, 1981, 1057).

Perhaps UK executives could themselves better appreciate nonacademic compared to academic OR people because of UK businessmen’s disregard of academic qualifications. Board-level executives in the top 100 UK corporations had significantly lower levels of education compared to, say, their French counterparts, even after the big push to upgrade levels of education for UK businessmen in the late twentieth century. Whereas in 1998 in France, 44.5 percent of board members of the 100 largest corporations had diplomas from the top ten ranked schools and 90.5 percent of them at the graduate degree level, only 16.4 percent of board members in the largest 100 UK corporation had diplomas from the top ten schools, and of them only 38.1 percent were graduate degrees (McClean, Harvey, and Press, 2007, 542).

There was hardly any complaint in the JORS about the absence of OR studies in British universities. On the contrary, articles primarily criticized the OR that was taught in them. Practical OR people even denied the relevance of the mathematical models proffered by academics, arguing that they were a poor yardstick with which to judge the health of OR in Britain. N. R Tobin, K. Ripley, and W. Teather, in “The Changing Role of OR,” observed:

The implication is that a dichotomy existed in British OR between the academics following the Americans and the practical men who still gave useful advice to British management because they ignored the abstraction of the academics. Apparently, large numbers of OR scientists in Britain, like businessmen, shared the traditional and deep-seated English suspicion of academics. Both the OR Society and its journal, like all British professional associations, were started by practitioners, not academics. “The low proportion of academic members in the [Operational Research Society] reflects the growth of the UK Society as a body to encourage the exchange of practical experiences” (Haley, 2002, 85).

Practical OR people in the UK and the US believed that their work benefited clients, and there were successes in this regard. The petroleum industry’s decisions on product mixes were never the same after the publication in 1952 of “Blending Aviation Gasolines: A Study in Programming Interdependent Activities in an Integrated Oil Company” (Cooper, 2002; Bixby, 2002). Given that in this case a demonstratively better decision process provided an optimum solution to a financially important decision problem in a competitive market, the better decision procedure, mathematical programming, was widely adopted for an entire class of tractable problems. If such particular successes could have been generalized, the expectation would have been that, with more experience in dealing with problems and perfecting their methods, the proportion of successes to failures would significantly increase through time. Actually, the opposite happened.

In 1981, Dando and Bennett evaluated the evolution of the mood of UK operational researchers as reflected in the pages of the Journal of the Operational Research Society (JORS), by looking at the issues published in 1963, 1968, 1973, and 1978. The credo affixed to the masthead of the journal when it started had read:

Up to 1968 when “optimism about the future of OR” reigned, there was “almost a total lack of criticism and debate in the journal.” In 1973, papers began to enounce considerable doubt about the practical effectiveness of OR, a doubt which by 1978 was being voiced in about one quarter of the major papers appearing in the journal. The essays of the late 1970s were, therefore, a culmination of a decade of ever-increasing and deepening concern about the usefulness of OR at the very center of the new paradigm.

The pessimism deepened when the subject of long-term prediction came up. The comments of Roger Collcutt on planning studies for a third London airport illustrate this concern. He observed that “alternative sites [for the airport] cannot be reliably distinguished by OR or any other method other than political. [About all that OR studies could do] was suggest the feasibility of various futures which in certain circumstances may look desirable” (Collcutt, 1981, 368). With all the “mays” and “mights,” a defense of OR obviously conceded much to its critics.

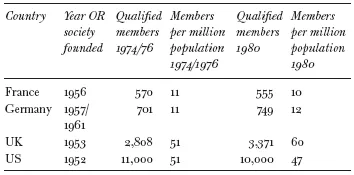

A stagnation if not decline in Operational Research Society memberships also indicates that all was not well. Whereas membership grew between 1964 and 1974 at an annual rate of 20 percent, subsequently growth rates fell dramatically (Rivett, 1974). Table 1.1 furnishes comparative data on OR professional society participation in France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States. OR groups in these four countries were, in terms of numbers of qualified members, the four largest in the world. Among these four groups, two, the British and American, were by far the largest, judged both in terms of members per million inhabitants, and members in absolute numbers. Of the two leading countries, the British were slightly ahead of the Americans in membership per million inhabitants. These two nations dominated the operations research movement; indeed, whereas in 1980 OR societies in the UK and the US had 13,371 members together, those in all of Europe had only 4,720. The doubts that had cropped up had occurred in the countries where OR had the greatest experience and following.

Table 1.1

Membership in operations research societies in Europe and the USA

Source: H.-J. Zimmerman, “Trends and New Approaches in European Operational Research.” Journal of the Operational Research Society 33 (1982), 597–603, 598.

Since operations research and management science are generic terms, misgivings about their efficacy actually covered a variety of managerial activities. They pertained to OR work in firms and in local and regional governments. Wilbert A. Steger pointed out that during the 1960s “a virtual avalanche of urban/regional models about new planning, program analysis, budgeting and other ‘futuristic’ decision-making and policy related decision-making [appeared]” (Steger, 1979, 548). But he noted how unsuccessful the OR techniques were: “When reviewing this era, it is difficult not to wonder at the relative lack of sophistication … [T]he assessment techniques … proved not to be very useful and often caused more damage than good in dozens of overly literal applications.” In the US, criticisms extended to the management techniques adopted in the national bureaucracy, the most famous being the Planning, Programming, and Budgeting System (PPBS) installed in the Pentagon in 1962 and in 1965 extended to other government agencies. Although designed to make decisions scientifically, that is, to optimize the means by which tasks are decided and realized, PPBS, Waddington observed, “has failed everywhere and at all times. Nowhere has [it] been established and influenced governmental decisions according to its own principles. The program structures did not make sense to anyone. They are not, in fact, used to make decisions of any importance” (Hofstede, 1978, 460). In 1972 the PPBS system was terminated (Gruening, 1998, 8).

No group so fundamentally misread reality as those who implemented and used PPBS in the Pentagon during the Vietnam War. The complaint, moreover, is more than political. It is also technical, for PPBS did not fail just because the Americans who implemented it were discredited by the Vietnam venture. They lost the war because they also did not understand the limitations of rational management methods such as PPBS, limitations prescient people knew at the time (Rosenzweig, 2010).

Other government scientific management techniques produced similar outcomes – in President Carter’s attempt to implement a sibling of PPBS, the Zero Based Budgeting Procedure in the federal administration (abandoned because of its “inadequacies”), in the introduction in French administration after 1963 of a scientific management process similar to PPBS (RCB, Rationalisation des Choix Budgétaires), which suffered, people later discovered, from “excessive hope” (Lequéret, 1982, 16). The reasons for meager results of optimization techniques in governmental affairs and operations are complicated. An important one is that the complexity of the decision problems in real government organizations makes optimization impossible; the irreducible characteristics of the problems grossly violate the assumptions required by the various optimization techniques. Another reason – one which is not always acknowledged – is that governmental problems amenable to optimization sometimes have great difficulty attracting the political attention and funding required to optimize.

“OR problems can never be a perfect representation of a problem,” the OR guru Russell Ackoff concluded, in a startling volte-face at the end of the 1970s (Ackoff, 1979, 102). “They leave out the human dimension, the motivational one;” indeed, he affirmed that the successful treatment of managerial problems deserves “the application not only of science with a capital S but, also, all the arts and humanities we can command.” Arts and humanities take mythopoetic dimensions of decision problems into consideration that express tacit-bonding skills and even sensory modes of communication essential to collaborative work.

For people managing nationally important operational events, imaginative management thinking should have started where the numbers left off. With managers captive to numbers-determinant thinking, too often excessive violence, environmental destruction, social disruption, waste of public resources, and national disgrace resulted.

Crumbling epistemologies:

a critique of the new paradigm

While contemporaries questioned OR, at a more profound level they also in the 1980s scrutinized the epistemological foundations of management sciences – indeed of traditional science itself – in a powerful dissent from the postwar consensus about managerialism and the value of the toolkit that neoclassical economists had introduced into business school education between 1960 and 1980. The debate had a practical dimension because it encompassed the organizational challenge that Japanese manufacturing now posed to American managerialism, and it had serious consequences because as people changed their minds, this disrupted careers.

The transformed life of one management expert, H. Thomas Johnson, illustrates the practical consequences of this intellec...