![]()

A world without the Minotaur

Almost two years have passed since the first edition of this book was written.1 Its prognosis for our tormented beast was not good. Have events since confirmed that the Global Minotaur’s wounds were too deep to allow it to continue to perform its miraculous global surplus recycling? Is this still the best explanation available as to why the American, the European and, indeed, the global economies are stuttering, and why generalized insecurity has become the ‘new norm’?

To be worthy of serious consideration, a theory of what went wrong with the global economy must not only offer a logical explanation of the past but must also describe the future developments that would falsify it. Would the argument that was the kernel of this book’s first edition pass such a test in the light of the last two years? Before addressing the question, it may be helpful to restate clearly (and with the help of a diagram) the book’s overarching ‘Global Minotaur Hypothesis’. Once the reader is reminded of the hypothesis, a series of ‘facts’ that would have falsified it will follow. As I hope to show in the remainder of the chapter, the original explanatory thrust, the Global Minotaur Hypothesis, survives the empirical test of falsifiability rather well. And, in so doing, it illuminates usefully the current policy debates unfolding on the drama’s three parallel stages: America, Europe and China.

The Global Minotaur Hypothesis: a summary2

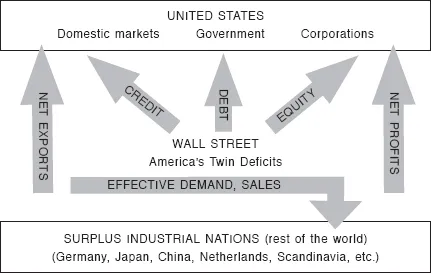

Since the 1970s, the United States began absorbing a large portion of the rest of the world’s surplus industrial products. America’s net imports were, naturally, the net exports of surplus countries like Germany, Japan and China; their main source of demand. In turn, the profits earned by the surplus nations’ entrepreneurs were returned, daily, to Wall Street, in search of a higher pay-off. Wall Street would then use this influx of foreign capital for three purposes: (a) to provide credit to American consumers, (b) as direct investment into US corporations and, of course, (c) to buy US Treasury Bills (i.e. to fund American government deficits).

Central to this global surplus recycling mechanism (GSRM), which I have likened to a Global Minotaur, were the two gargantuan deficits of the United States: the trade deficit and the federal government budget deficit. Without them, the book argues, the global circular flow of goods and capital (see diagram below) would not have ‘closed’, destabilizing the global economy.

This recycling system broke down because Wall Street took advantage of its central position in it to build colossal pyramids of private money on the back of the net profits flowing into the United States from the rest of the world. The process of private money minting by Wall Street’s banks, also known as financialisation, added much energy to the recycling scheme, as it oozed oodles of new financial vitality, thus fuelling an ever-accelerating level of demand within the United States, in Europe (whose banks soon jumped onto the private money-minting bandwagon) and Asia. Alas, it also brought about its demise.

Figure 9.1

The Global Minotaur’s global surplus recycling mechanism

When, in the fall of 2008, Wall Street’s pyramids of private money auto-combusted, and turned into ashes, Wall Street’s capacity to continue ‘closing’ the global recycling loop vanished. America’s banking sector could no longer harness the United States’ twin (trade and budget) deficits for the purposes of financing enough demand within America to keep the net exports of the rest of the world going (a financing process that, until the autumn of 2008, tapped the rest of the world’s surplus profits which these net exports produced). From that dark moment onwards, the world economy would find it impossible to regain its poise – at least not without an alternative global surplus recycling mechanism that replaces the wounded Global Minotaur.

This was, in brief, the central hypothesis of the book’s first edition. Did it stand the test of history?

The Minotaur is dead! Long live America’s deficits!

Had the global economy found its feet without some GSRM to replace the Minotaur, there would have been no new edition of this book (since an apology for the first one would have sufficed). Similarly, if the eurozone had bounced back, on the strength of its austerian policies, or if China had discovered some inner force by which to arrest the declining rate at which its people consumed, the book’s central pillar would have lain in ruins. Sadly, this is not what transpired: the world continues its journey in the uncharted waters of a dark ocean whipped up continually by the evil winds of dread and fear.

The fact that recovery has not spread its soothing wings over us is, of course, no proof that the ‘Global Minotaur Hypothesis’ holds. To reach the conclusion that the last two years have kept it alive and potentially insightful, we need to state carefully and in some detail its predictions and then to compare those with the facts. So, let us begin: what observations would we have to make regarding the past two years or so to conclude that the Global Minotaur Hypothesis was flawed?3

Suppose we observed that, despite the Crisis, America’s deficits remain high but that they continue to absorb the net exports of both goods and capital from the rest of the world, and at a pace not too dissimilar to that of the pre-2008 era. If this is what we observed in 2009 and beyond, then the Global Minotaur Hypothesis would be refuted: for it would then be impossible to claim (a) that the Global Minotaur is kaput, and (b) that its demise must be blamed for the world’s economic continuing woes.

So, let’s look at the facts: The first observation worth noting is that America’s twin deficits are alive and kicking. At the height of the Minotaur’s reign, in 2005, the US federal government posted a deficit of $574 billion. In the same year American consumers and firms absorbed a staggering $781 billion of net imports from the rest of the world. Almost 70 per cent of the profits that the non-American producers of these goods made returned to Wall Street. Once in the bankers’ hands, they were turbocharged (through so-called ‘financial engineering’) and, thereby, financed the US deficits, with the residual being exported to the four corners of the globe (where it helped build a variety of bubbles).

Following the 2008 catastrophe, America’s deficits diverged massively. As all sorts of incomes (from labour, capital and rent) collapsed, asset values fell through the floor, home foreclosures and the ranks of the unemployed burgeoned, it was inevitable that Americans would reduce drastically their consumption of imported goods. Indeed, in 2009 the trade deficit fell from $781 billion in 2005 to $506 billion. However, in the same year, the US federal deficit shot up (from $574 billion in 2005) to $1,400 billion, as government strove to prop up Wall Street and stimulate Main Street. By 2011 the trade deficit had recovered to, more or less, its 2005 level (reaching $738 billion) while the budget deficit stabilised at the historically gigantic $1,228 billion mark.

Granted that the Crisis did not dent America’s deficits (indeed, it boosted their sum), the pertinent question is this: did the United States manage, post-2008, to continue recycling other people’s surplus goods and profits at a pace that, judging from the pre-2008 period, is necessary to keep world total demand for produced goods buoyant? The answer that surfaces upon close inspection of official statistics is unambiguously negative. In brief, the facts confirm the hypothesis that the Global Minotaur is now defunct. Two pieces of data confirm this.

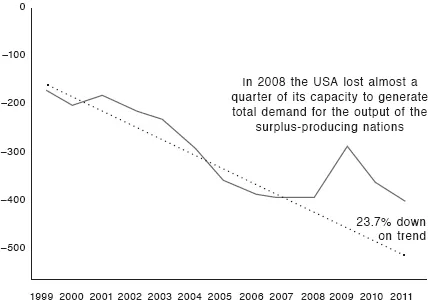

First, America has lost its capacity to recycle the rest of the world’s net exports at the pre-2008 pace. More precisely, in 2011 America was generating 23.7 per cent less demand for the rest of the world’s net exports than it would have been without the Crash of 2008. (See Figure 9.2 where it is evident that in 2011 the United States was absorbing almost 24 per cent less of the main exporters’ net exports than their underlying trend value.)

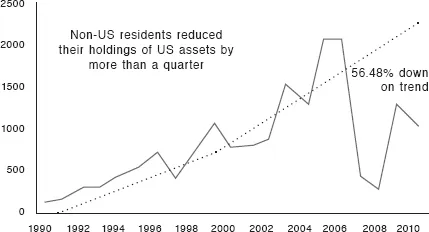

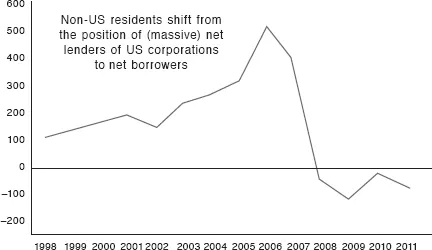

Secondly, and at the same time, America was failing to attract (through Wall Street) the level of capital flows necessary to maintain the pre-2008 pace of investment into its private sector. In particular, by 2011 the United States had lost 56.48 per cent of the assets held by foreigners compared to the (trend) level that would have been had the Crash of 2008 not happened (see Figure 9.3). The main, and indeed crucial, reason for this precipitous decline was that foreign net capital flows ending up as loans to US corporations fell drastically from around $500 billion in 2006 to –$50 billion in 2011 (see Figure 9.4).

In conclusion, a crystal clear picture is emerging: the Crisis did not alter the deficit position of the United States. The federal budget deficit more or less doubled while America’s trade deficit, after an initial fall, stabilised at the same level. However, the US deficits are no longer capable of maintaining the mechanism that keeps the global flows of goods and profits balanced at a planetary level. Whereas until 2008 America was able to draw into the country mountains of net imports of goods, and a similar volume of capital flows (so that the two balanced out), this is no longer happening post-2008. American markets are sucking 24 per cent fewer net imports (thus generating only 66 per cent of the demand that the rest of the world was used to before the Crash) and are attracting into the American private sector 57% less capital than they would have had Wall Street not collapsed in 2008.

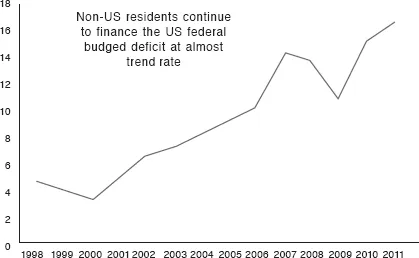

In short, of the mighty Global Minotaur, the only reminder that remains is the still accelerating flow of foreign capital into America’s public debt (see Figure 9.5), evidence that the world is in disarray and money is desperately seeking safe haven in the bosom of the reserve currency in this age of tumult. But as long as the Rest of the World is reducing its injection of capital into America’s corporate sector and real estate, while America is reducing its imports of their net exports, we can be certain that the beast is dead and nothing has taken its place with a capacity to re-start the essential process of surplus recycling. Thus the sad cry: The Global Minotaur is dead! Long live America’s deficits!

The Minotaur’s death in pictures

Figure 9.2 US goods trade deficit with major surplus countries, including the eurozone’s surplus member states, China, Hong Kong, Japan and Korea (US$ bn)

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Figure 9.3 Foreign assets in the US except derivatives (US$ bn)

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Figure 9.4 Corporate bond purchases (net) by non-US residents (US$ bn)

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Figure 9.5 US Treasury bond purchases (net) by non-US residents (US$ tn)

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

America after the Minotaur

Once Wall Street lost its ability to harness America’s twin deficits for the purposes of recycling the rest of the world’s surplus goods and profits, the American economy had to settle at a much reduced level of economic activity. This would not be a bad thing per se if it were not for the fact that the accumulated debts (e.g. unpaid mortgages and many bad loans that one bank had made to another) remain as if nothing had happened.

A lower level of economic activity would have, indeed, been fine as long as employment had picked up quickly and the lower wages were able, in conjunction with lower prices, to preserve a level of consumption consistent with calm but steady recovery. Alas, the success of the banking sector in ensuring that monetary policy was tuned towards their interests, just like in the good old (pre-2008) times, guaranteed that endogenous growth was out of the reach of American society. When taken together with (a) Europe’s suicidal dallying with Herbert Hoover-like austerity4 (at a time when half of the continent is in the clasps of its own Great Depression), and (b) China’s structural failure to stimulate domestic demand, it is no great wonder that the Crisis remains with us.

Chapters 7 and 8 described vividly the rise of bankruptocracy, the way in which bank failures armed the failed bankers with remarkable extractive, predatory political power, a power to extract a larger part of a shrinking national income at rates proportional to their banks’ black holes. We have already seen (see Chapter 7) the manner in which t...