![]()

SECTION 1

THERE IS NO PROBLEM

![]()

MYTH 1

HIGHER DEFENSE SPENDING EQUALS INCREASED SECURITY

‘If you want peace, prepare for war.’

So goes the much-repeated phrase, taken to heart around the globe. Indeed, the world spends a great deal preparing for war: at least $1,676bn in 2015.1 With such high levels of spending, and the innumerable threats that arms purchases are said to protect us from, it would be easy to accept this adage at face value: why on earth else would responsible governments pour such huge sums into military spending?

Unfortunately, the reality is a lot more complicated. While most reasonable people would agree that states should be able to legitimately defend themselves and their citizens, it is unclear that large outlays on defense make a consistently measurable difference in providing security to the countries that buy weapons. Moreover, there is solid evidence showing that, in certain instances, spending money on buying weapons may actually decrease a country’s security. Just one of these is the situation referred to as the classic ‘security dilemma’ of setting arms races in motion: three others are also explored in this chapter. For example, in states where the purchasing government is undemocratic or corrupt, there are incontrovertible examples where a government uses weapons to the detriment of the security of citizens.

HOW MUCH IS SPENT?

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) estimates world military spending in 2015 at $1,676bn.2 As a share of global economic output (gross domestic product, or GDP), this amounts to 2.3% globally.3 This is almost certainly an underestimate, as it excludes some countries such as North Korea where meaningful dollar figures cannot be calculated, and cannot capture the considerable ‘off-budget’ military spending that occurs in many countries, for example by using oil revenues to buy arms without including it in the national budget.

During the Cold War, both NATO and the Warsaw Pact spent vast amounts on their militaries. For over forty years the US and the Soviet Union engaged in an arms race, both conventional and nuclear. Each did so largely out of fear of the other’s intentions, seeking nuclear deterrence and the capability to win a third world war, while at the same time generating increased fears and insecurity in the other. When the Cold War ended, the Western public discovered that NATO had hugely inflated their estimates of the Soviet military capability. The fears were real, but they had been exaggerated.

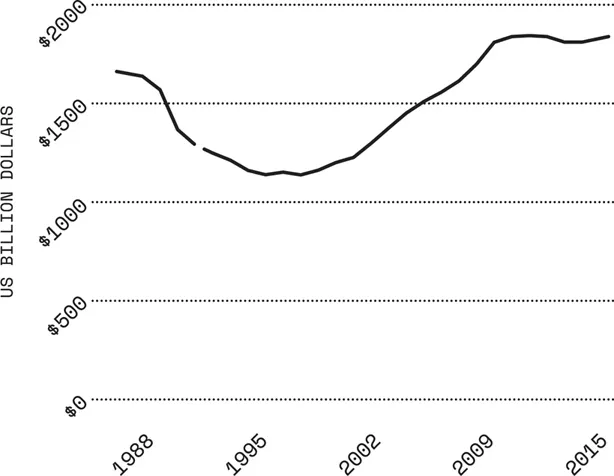

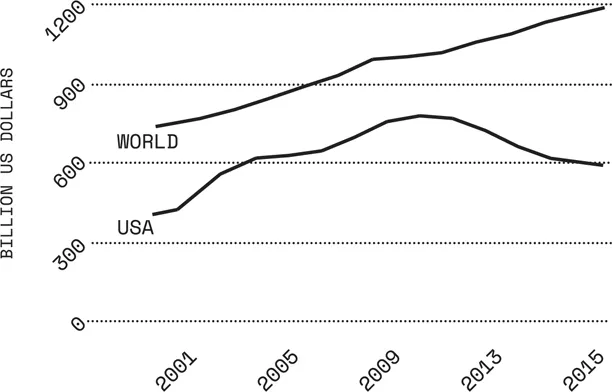

With the end of the Cold War, there was a great deal of hope that countries would divert defense funds into social development: what was known as the ‘peace dividend’.4 Signs were initially good: at the end of the Cold War, military spending fell significantly in real terms (i.e. adjusted for inflation) up to the mid-1990s. But military spending started increasing again after 1998, and much more rapidly after 2001, in the aftermath of 9/11 (see Figure 1.1). Between 2011 and 2014, the global economic crisis and the austerity that was attendant upon it precipitated a fall in global defense expenditure. In 2015, however, global defense expenditure increased from its 2014 level—a sign that defense expenditure is regaining ground lost during the economic crisis. And what was particularly notable prior to 2015’s turnaround was how much the ‘rest of the world’ picks up the slack in defense expenditure: between 2011 and 2014, as defense budgets were reduced in the West, the ‘rest of the world’ was increasing its expenditure year-on-year.

Figure 1.1 World military expenditure, 1988‒2015 (constant 2014 US$bn)

Note: The absence of data for the Soviet Union in 1991 means that no total can be calculated for that year.

Source: SIPRI, Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2015.

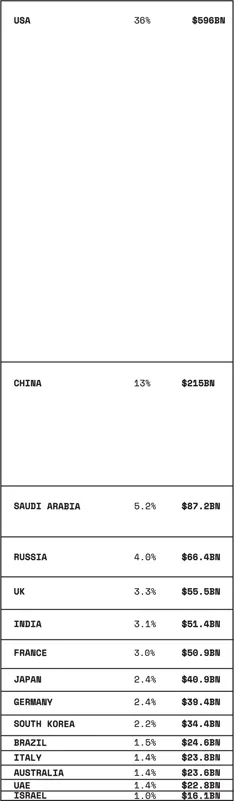

Figure 1.2 15 countries with the highest military expenditure in 2015

Source: Extrapolated from the SIPRI Military Expenditure Database 2016.

Despite recent falls in the West and increases in the rest of the world, Western countries still account for a majority of global military spending. NATO members, including the US, spent a total of $904bn in 2015, 53.9% of total world military spending.5 Other countries that the US classes as ‘major non-NATO allies’, including Japan, Australia and Israel, accounted for another 10% of the total. Eight of the top fifteen military spenders worldwide are either NATO members or major US non-NATO allies. Nonetheless, countries outside the West have become more prominent amongst the major spenders, with China, Saudi Arabia and Russia now the second, third and fourth largest spenders worldwide.6

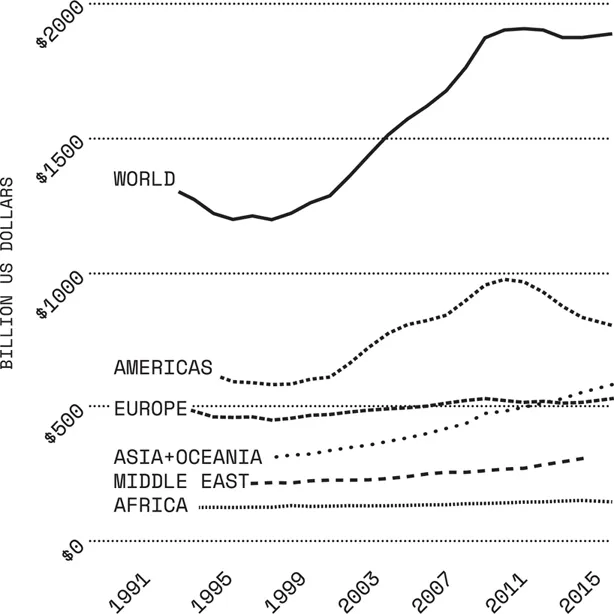

The dominance of the top fifteen spenders should not obscure another important trend: military expenditure is growing rapidly globally, even in some of the poorest regions of the world. Indeed, SIPRI identifies twenty-three countries that have doubled their military spending between 2004 and 2013. Among them are some of the world’s poorest nations. In Africa, for example, military spending rose over 8% in 2013 and 5.9% in 2014—adding up to a 91% increase overall since 2005.7 Admittedly military expenditure fell in Africa in 2015 by 5.3% (the first time in eleven years) to $37bn, but this is still a massive 68% higher than it was in 2006.8 This is matched elsewhere: world military expenditures, despite a slight leveling in 2013, have steadily climbed over the past decade—outpacing economic growth.9 China, the nation with second highest military spending, has increased its defense budgets by double digits almost every year for the past twenty, well outpacing even its impressive GDP growth and sparking defense spending increases in wary regional neighbors South Korea and Vietnam.10 Further, Japan joined the top ten military spenders in 2013 and, in 2015, approved the decision to reverse its post-World War II constitutionally engraved ban on its forces fighting overseas.11 Russia has increased its military spending 92% since 2010 alone.12

Regional increases, possibly indicating arms races (where increasing military expenditure of one country leads another to spend more, thereby encouraging the original country to spend even more, triggering further regional spending and so on), have occurred in the Middle East, where Saudi Arabia vastly expanded its defense budget by 97% between 2006 and 2015; in Africa, where overall expenditures have been growing by 5‒8% annually (until a surprising drop in 2015) with Algeria and Angola leading the way; and in Asia and Oceania, which witnessed a 64% increase between 2006 and 2015 (and a 5.4% increase in 2015 alone), spearheaded by Chinese defense budget increases.13

Figure 1.3 Defense spending by region, 1992–2015 (constant 2014 US$bn)

Source: Extrapolated from the SIPRI Military Expenditure Database 2015.

Despite regional and global increases, the United States remains far and away the world’s largest spender on its. Because it spends so much beyond any other country, it is worth a close look at the purchasing power of this super-sized budget.

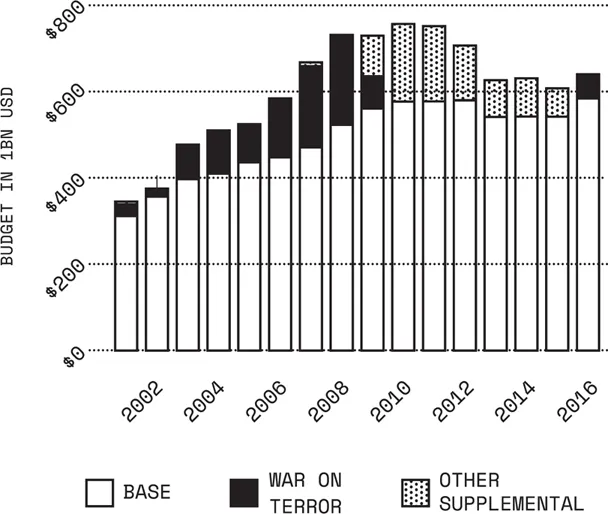

Defense spending consumed 16.3% of the total US federal budget in 2015.14 In absolute terms, its total national defense spending in 2013, even discounting funding for the ongoing war in Afghanistan, remained near what it was in 1985, the previous peak (it should be pointed out that, as the US has become richer in the interim, defense spending as a percentage of GDP has fallen: it was 6.8% at the height of the Reagan reequipping era, 5.7% in 2011 and 4.5% in 201515). In that era, of course, historically high defense spending was deemed necessary as part of an existential struggle with the USSR (although it has subsequently emerged that the USSR’s military capacity was often overstated).16 For the year 2016, the Pentagon enjoys a $534.3bn base budget and the $50.9bn Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) budget (a total of $585.2bn).17 Further, the US is currently on track to fund the most expensive weapons program in human history, the F-35 fighter jet, which will cost roughly $1.4trn to build and operate over its lifetime.18

Figure 1.4 US military spending versus the rest of the world, 2000–2015 (constant 2014 US$bn)

Source: Extrapolated from the SIPRI Military Expenditure Database 2015.

Figure 1.5 DoD budgets, FY 2001–2016

Note: from 2010 onwards the category ‘Global War on Terror’ is no longer used in the accounting of the Comptroller General of Defense. The Global War on Terror is replaced by the account line Overseas Contingency Operations. This has been added to other discretionary supplements, such as spending on Hurricane Sandy relief in 2013, to produce the figure for ‘other supplemental’.

Source: Extrapolated from Office of the Under Secretary for Defense (Comptroller), National Defense Budget Estimates for FY2016, United States Department of Defense, March 2015, Table 2-1, p. 22, accessed May 31, 2016, http://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/fy2016/FY16_Green_Book.pdf.

The Pentagon’s spending is in addition to the $71.6bn intelligence budget for fiscal year 2016, which includes drone warfare conducted in Pakistan and Afghanistan, and massive digital surveillance channeled, for example, through the National Intelligence Program, including the CIA, NSA, National Reconnaissance Office and National Geospatial-Intelligence Program.19 If all these items are added together (the base budget, contingency spending and intelligence) for 2016, the total is $656.8bn: a truly enormous sum.

DOES DEFENSE SPENDING LEAD TO SECURITY?

With so much being spent on defense, it is only natural that we ask whether or not it is being well spent. Unfortunately, there are a number of ways in which spending on defense may actually make us less secure. We will discuss the most common ways here, but there are other, more complicated, impacts that defense spending can have on security around the world, which we will address at the very end of this chapter.

The security dilemma

The first way in which military spending can actually reduce security is through what is known in international relations theory as the ‘security dilemma’,20 or the ‘spiral of insecurity’. The ‘security dilemma’ occurs when a state with no hostile intentions believes that states around it, while not necessarily expressing any outward enmity, could pose a long-term security threat. The state responds by increasing its own sense of security through building up its defense capacities. However, states around it see this increase in defense spending, and come to believe that the original state now has hostile intentions; they, in turn, increase their own defense capacities. This cycle continues as both parties increasingly divert resources towards their own defense, leading to an arms race. This ‘spiral of insecurity’ can, in the worst case scenario, lead to actual conflict. This is not to suggest that conflict follows inexorably from arms races; the data is much too complicated for that.21 And, as we will demonstrate later, arms sales often have nothing to do with perceived or real security threats. But in certain cases arms races undoubtedly play a role, such as in the case of the developments that led to World War I.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Germany’s leaders had come to believe that it was being surrounded by hostile forces including Russia, France and Great Britain. In response, Germany started to build up its military forces, in particular its naval forces, which all other parties began to believe was evidence of Germany’s ill intentions. Great Britain, which had built its military power on its navy, was particularly alarmed. The other three parties, seeing this, also increased their weapons, leading to an enormous arms race. This race created tensions between all the states; so much so that, when a political crisis unfolded upon the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, Austria-Hungary and Russia both mobilized and Germany then invaded its neighbors, provoking one of the deadliest conflicts in human history. The arms race may not have been the cause of World War I (human affairs are always more complicated than that), but it was a substantial contributor to the tensions that led to war.

Is China’s Growing Military Expenditure the Result of the ‘Security Dilemma’?

China’s rapidly rising military expenditure and capabilities are generating considerable fears amongst some of its neighbors, especially Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines; and all countries are all now increasing military spending in response.22 (Vietnam has been doing so for several years, the others more recently.) These...