![]()

1 | Introduction: another world is possible – how do we know?

Global elites, their political henchmen and media sycophants insist that economic growth, international trade, the elimination of subsidies and privatization will alleviate poverty. Activists’ blossoming confidence that another world is possible is well-rooted. Analysis of the effects of structural adjustment and free trade policies reveal that their promises are unfulfilled. Indeed, their impact has been perverse. Apparently, globalization works only for the rich. Even high-profile administrators of neoliberalism have deserted. Their insider revelations1 are hardly news to the non-governmental organizations which had been carefully collecting data for decades.2 Inequality has increased in nearly every country; internationally,3 the conditions of life for the poor and indigenous peoples have steadily deteriorated; and the environment on which we all depend has been irrevocably damaged.

In what ought to be the invitation to its formal suicide, the World Bank admits that its structural adjustment programmes undermine its core economic shibboleth: economic growth. Damning also is the collapse of the obedient ‘developing nations’ of South-East Asia and Latin America, as well as the failure of the command-capitalist South Korean regime (the only country ever to graduate from ‘Third’ to ‘First World’ status). The evidence has accumulated to the point that, for those familiar with it, there is little further to be discussed. The holy trinity of export/trade/growth is exposed as a manipulative fraud and each new invocation of the dead and absurd promises of development – that it will bring peace, heal the environment or end poverty – is more transparent than the previous.4 The economic and political system promoted by globalization is not only morally bankrupt, it is no longer credible as economics.

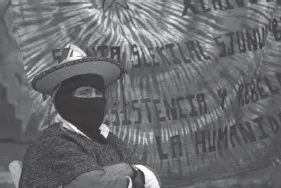

1 Zapatista members celebrate the first anniversary of the founding of their Caracoles, cultural centres of resistance, and the formation of the Councils of Good Governments in the rebel highlands village Oventic in Chiapas, Mexico, 8 August 2004 (photo by Tim Russo).

This book is intended to familiarize interested parties with the anti-globalization movement and to provide direction for further research and exploration of the ‘movement of movements’. Because many exhaustive analyses of the machinations of globalization have already been written (you have probably read several of them) and because this book focuses on the resistance to globalization, this introduction will provide only a rudimentary review of the basis for opposition. Herewith, globalization’s most egregious deceptions.

Globalization’s thirteen biggest lies

1 Globalization is old Globalization’s marketing strategy steals the images of family, multiculturalism, communication, women’s liberation, travel and trade and offers them back to us, glamorized and at a price. All of these things existed before colonialism and contested it at every stage of its development. These images obscure the structure of globalization, its macro-economic policies, and the corporate projects it promotes – all of which damage families, communication and culture. Describing itself as a ‘constitution for a new global economy’, the World Trade Organization (WTO) is designed to subvert existing international human rights and labour law, national sovereignty and parliamentary regulation. The highest international law (and the only enforceable one) is now ‘free trade’, a highly specified set of principles sometimes described as a ‘bill of rights’ for multinational corporations, multinational corporations, to which the laws of signatory countries are now secondary.

2 Globalization is new Globalization pretends to bring a new, ‘rules-based’, fairness and structure to the global trading system, but activists in the Global South call it ‘recolonization’.5 Not only does it force Third World nations to implement policies remarkably similar to those imposed by colonial administrations, it also reverses the gains of postcolonial governance in areas such as land reform, the nationalization of industries and cultural protections. Moreover, the ‘free trade agreements’, so ‘new’ that they have not yet been fully implemented, can already be evaluated by their predecessors of nearly two decades, the Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The results of SAPs have been a steady increase in inequality6 and the ruthless liquidation of economies to service the debt.

3 Globalization may be exploitative or dislocating at the margins, but it’s ‘better than nothing’ for the majority of the poor Today’s poor, and their regions, were self-sufficient for millennia. They were colonized for their mineral, timber, soil, human, animal and climatic wealth. The idea of a poor or hungry Africa or Asia or Latin America is absurd. Northerners who point to a line of people hoping for a job in a sweatshop and praise the Global North for generously providing jobs are peddling ahistoricism and paternalism.

Twenty years ago the people now queueing were independent small-scale producers, farmers, processors, craftspeople or artisans producing for local markets. Visitors depicted these sustainable livelihoods as backward and dirty, and leaders of Global South countries (already pummelled by centuries of their colonists’ ethnocentric definitions of civilization) were seduced by visions of modernity.

Those appalled by pious arguments that slavery, despite its brutality, did a big favour to Africans (who at least were given the chance to become Christians and learn discipline) may soon find ourselves ashamed to have countenanced sweatshops, let alone congratulated the sweat-traders for ‘providing jobs’. Neoliberal forms of development are never going to solve poverty, protect the environment or bring peace – these are dead promises. Instead, so-called ‘development policies’ primarily benefit global elites, at the cost of traditional, sustainable livelihoods, the local economies they support and the resources on which they depend.

4 Globalization frees the market to satisfy important human needs Human needs such as hunger are not a ‘market demand’ – that is a privilege reserved for those whose needs and desires are backed by buying power. Since hungry people lack exactly that, a market-based food system will easily pass them by.7 Instead of meeting human needs, neoliberalism invokes them as a façade while steadily undermining local provisioning.

Multinational corporations are able to profit from and intervene in local production through agricultural technology schemes which create dependency on expensive inputs. As postcolonial countries are pressured to export more to earn foreign exchange to pay their debts and to open their markets to imports, farmers simultaneously become dependent on volatile world prices while losing access to formerly protected, stable national markets. The same international trade system that promises ‘cheap food’ for the hungry and whose major players advertise their technologies and practices as absolutely essential to the task of ‘feeding the world’, in fact undermines national food production. The companies who make those promises undercut local producers with subsidized imports. As a result, nations lose food security and control over domestic food policy. Simultaneously, the WTO’s SPS (Sanitary and Phyto-Sanitary) agreements undermine local value-added production by imposing sterilization and packaging standards which only multinational food corporations can afford. Meanwhile, artisans and craftspeople are undercut by low-quality mass-produced baubles whose only cultural value is a desperate scrap of Western style.

Aggressive marketing campaigns mobilize colonial ideology to manipulate food preferences and endanger local food cultures. Images of the Global South (particularly Africa) as ‘hungry’ are used to force biotechnology (a technology which has been rejected by farmers and consumers in the North) on Global South countries where farmers and consumers have made it clear they also do not want it.

5 Globalization is about deregulation to ‘free’ the market from burdensome government regulations Interestingly, globalization policies do not follow any classic economic orthodoxy. They force deregulation when environmental protections, labour law or land reform are in the way of business operations. They force regulation to ensure patent payments or to create requirements that are cost-effective only for large-scale producers (handily disposing of competition from small, local competitors). These convoluted rules are designed to commodify life and then enable corporations to control and profit from trading the commodity.

6 Globalization increases consumer choice Citizens of most countries are demanding the right to choose whether or not they will eat biotech foods (genetically modified organisms, GMOs, or living modified organisms, LMOs). Most countries have some kind of label or restrictive scheme and the Biosafety Protocol recognizes countries’ right to regulate their imports. But ‘free trade’ rules are rapidly overriding any legal invocation of the ‘precautionary principle’ which was, until recently, the basis of most law governing the marketing of new technologies.8 Consumers receive the illusion of choice between brands and artificial flavours while choice over the more serious fundamentals, such as conditions of production, health risks and environmental impacts of products, are eliminated. In the end, the global market offers force not choice.

Even the most superficial consumer choices do not make it to the majority of the world, 2.8 billion of whom live on less than two dollars a day, which is the United Nations Development Programme’s definition of absolute poverty and are losing control over the most basic choices as they are forced to migrate far from home and family to sell their love in the nanny market and their bodies in the sex trade.9 Multinational corporations are exercising power not only to shape global, national and local economies, the concentration of wealth, the treatment of labour and political sovereignty, but also more qualitative aspects of life – defining science, shaping culture, standardizing and controlling our desires and definitions of dignity, delimiting public space and having no respect for the sacred.10

7 Globalization is democratic The World Bank and IMF evade mechanisms of international democracy by operating as ‘proxy governments’ of the USA, which controls the crucial proportion of votes.11 WTO ministerials are collapsing not because elites of the Global South are unwilling to exploit their own people, but because these meetings are so undemocratic that they insult these elites and are politically untenable in sovereign postcolonial nations.12 The WTO claims to work by consensus, but what that really means is simply that it will never allow voting, as the G8 (Group of Eight: the most powerful industrialized nations: France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK, the USA, Canada and Russia) would be outnumbered. The ‘consensus process’ – described as ‘bullying’ by Global South participants – is one in which documents are written by a small group dominated by G8 interests and then present...