![]() p class="imagec">

p class="imagec">

1. Energy for households

Energy poverty denies millions of people the basic standard of living that people want, need and have a right to. Without access to energy to cook, heat the home, earn a living and fully benefit from health, education and cultural opportunities, whole communities are trapped in lives of drudgery and subsistence. This chapter examines the impact of energy poverty on poor people and communities. It also highlights the transformational effects made possible when energy becomes available.

From the perspective of poor people, the energy service (sufficient light, warmth, etc.) is more important than the source. Although different supplies and appliances can be used for multiple services (a stove for both cooking and heating rooms in cold climates and at night), this chapter focuses on five service categories that comprise the key dimensions of energy access for households.

•lighting

•cooking and water heating

•space heating

•cooling

•information and communications

This chapter is based on data from diverse national and regional reports and studies, which have been collated from across Africa, Asia and Latin America. Project- or initiative-level data have also been incorporated, especially where national or international numbers are weak. It also draws on the testimonies of people living in energy poverty or who have recently benefited from access, via interviews and focus group discussions. In compiling this information, a marked lack of comprehensive and disaggregated international energy access data was noted. A full roll-out of the Global Tracking Framework (Banerjee et al., 2013), a recent initiative of the World Bank, supported by Practical Action, should help to address some of these gaps in future years.

For each energy service this chapter highlights the current situation for poor people and the implications of this lack of access. It discusses options for improving access and the impact this can have on the lives of poor people. A minimum standard applicable to each service is suggested. This is to some extent, controversial and country specific, however it is an important step in quantifying what universal access to energy entails in reality (one of the aims of the UN’s Sustainable Energy for All Initiative (SE4ALL) by 2030).

Lighting

Lighting is a fundamental human need. People who cannot flick a switch to light their homes lose many productive hours as soon as the sun sets. The estimates are that in 2010, 1.2 billion people (17% of the global population) did not have access to electricity (Banerjee et al., 2013). As a result, people resort to lamps that are polluting, dangerous and provide low-quality light such as candles, kerosene lamps or even simply flaming brands. And yet these lights are usually more expensive than electric lighting.

1.2 billion people (17% of the global population) did not have access to electricity

Lighting without electricity

The main problems faced by poor people trying to light their homes without electricity are the low quality of the light, high costs, and the health dangers from burns and smoke.

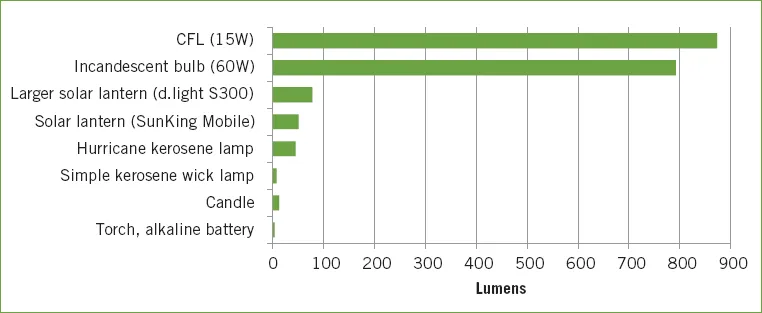

Quality of light. Lights using energy sources other than electricity tend to be far dimmer. A kerosene wick lamp or a candle provides just 11 lumens2 compared with 1,300 lumens from a 100W light bulb. Electric lamps are also much more efficient than kerosene in converting energy into light. A simple wick bottle lamp burns 10 ml of fuel per hour and gives out light equivalent to that from a small electric flashlight (torch) – too dim for reading. Respondents to a national rural lighting survey in Peru reported that candles and kerosene lamps provided barely enough light to walk around the house (Barnes, 2010a). They do not provide enough light for safe work or study. Households with higher incomes tended to use car batteries to power electric lights, but limited their use because of the costs and inconvenience of recharging the batteries.

Cost of lighting. Studies have repeatedly shown that the running cost of lighting from candles or kerosene is far higher than from electricity. They also show that running inefficient bulbs from large batteries is more expensive than lighting from good-quality solar lamps. The cheapest source of light is still using grid electricity with energy efficient light bulbs. A World Bank study in Guatemala (Foster et al., 2000) found that the household purchase price for a unit of light was 0.08 US$ per kWh for mains electricity compared to 5.87 for kerosene and 13.00 for candles, making them 162 times more expensive than mains electricity per unit of light. SolarAid has found that on average solar lights save African families around $70 per year.

The hurdle of the initial cost of a solar lamp, and in some cases the lack of availability, have restricted their uptake. However this is beginning to change quite rapidly with recent advances in technology design and quality standards, and the development of dynamic solar lantern markets in several countries.

The dangers of lamps: household air pollution (HAP) and burns. There are few studies on the levels of household air pollution from kerosene lamps. A preliminary laboratory study in Guatemala (Schare and Smith, 1995) indicates an average particle emission of 540 mg/hour for wick lamps and 300 mg/hour for enclosed lamps. Compared to biomass stove emissions (2–20 g/hour), this emission rate is relatively low, but the most polluting lamps emit levels that are similar to those from the cleaner types of biomass stoves. A study by Poppendieck et al. (2010) indicates that pollutants from the cheapest kerosene wick stoves have the smallest particle size, and are thus the most dangerous since they are taken more deeply into the lungs.

Unguarded candles and wick lamps are intrinsically unsafe and lead to injury and deaths, particularly among women and children. In Sri Lanka, 91 of the 221 patients (41%) who were admitted to Batticaloa General Hospital with burns between July 1999 and June 2001 cited lighting as the cause. During 1998 and 1999, 151 of 487 patients (31%) aged 12 years and older who were admitted to the National Hospital in Colombo had accidental burns from kerosene lamps (Peck et al., 2008).

Figure 1.1 Amount of light from different sources

Source: Mills (2003) and product descriptions on Lighting Africa website

Table 1.1 compares some of the technologies that are now available. This is a rapidly developing sector and new products and innovations are coming on stream all the time.

The impact of adequate lighting

Studies suggest that having access to lighting is hugely valued by poor families. A study in Rwanda found that once grid electricity was available, 80% of households switched completely from traditional lighting sources (GTZ and Senternovem, 2009). SolarAid’s impact report found that rural African families were saving around $70 per year with the money commonly spent on better food, education and farming. Children were spending an average of an extra hour studying per night. There were more qualitative impacts, with lighting bringing people together and helping them feel safe and secure after dark (SolarAid, 2013).

Minimum standard for adequate lighting

In its Energizing Development programme (EnDev), GIZ proposes that a minimum acceptable level of light in a household is 300 lumens (comparable to a 30W incandescent bulb). In workplace settings it has been found that this is a threshold below which there is a rapid increase in accidents (Reiche et al., 2010), however 300 lumens is sufficient for reading and other household tasks. This report argues that 300 lumens should be available for a minimum of four hours per night.

Cooking and water heating

Cooking is a daily need, with around 80% of the foods humans consume needing to be cooked, and yet this is a relatively neglected area of intervention. In 2009 a study found that only 2% of energy strategies in the least developed countries addressed cooking (Havet et al., 2009).

Two in every five people rely on wood, charcoal or animal waste to cook their food

Two in every five people (2.8 billion in 2010) rely on wood, charcoal or animal waste to cook their food (Banerjee et al., 2013). Only 27% of those who rely on solid fuels (biomass or coal) are estimated to use improved cookstoves. Access to these stoves is even more limited in least developed countries and sub-Saharan Africa, where only 6% of those who use traditional biomass are taking advantage of such options (Legros et al., 2009).

It is not just cooking that requires a source of heat: sterilizing water and heating water for washing and personal hygiene extend the amount of time for which a stove or fire must be lit. Stoves are also used for home-based productive activities such as cooking animal feed, brewing beer and spirits, and cooking street food (often an important source of household income).

Cooking and water heating does not only take place in the home, but also on the streets (for street foods), in cafes and restaurants, and in institutions such as schools, hospitals and at workplaces.

Table 1.1 Low-cost lighting technologies and their uses

Cooking and water heating without improved stoves or fuels

There are far-reaching implications of the lack of access to improved cooking solutions. Some of the most important relate to women and children’s time and workloads, health and environmental issues.

Women’s time and workload. Women in particular spend many hours in drudgery, gathering fuel, cooking over inefficient stoves and cleaning soot-laden pots, clothes, walls and ceilings. Studies in various countries suggest women (and often children) spend 2–8 hours per day collecting wood (Figure 1.2). There are also wide seasonal variations affecting the availability and choice of fuel types (Box 1.2).

Pneumonia caused by inhalation from cooking fires causes half the deaths of children under five

Health issues. For those with the lowest incomes, who cook and heat water using biomass fuels on rudimentary stoves, smoke is one of the largest causes of ill-health and death. The Global Burden of Disease study 2010 (WHO) estimates that exp...