![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introducing Kurdistan

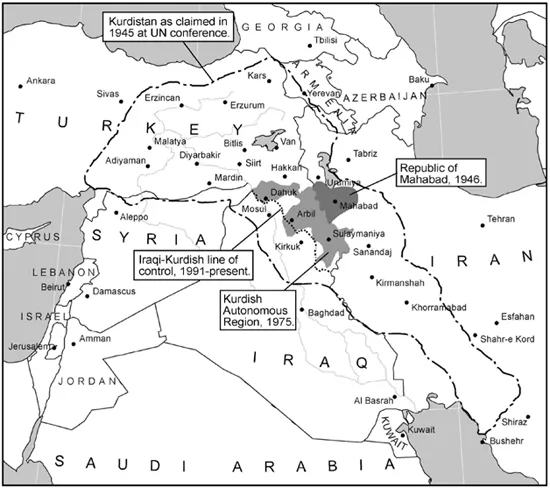

Kurdistan, or the homeland of the Kurds, is a strategic area located in the geographic heart of West Asia. The Kurds are an ancient race that inhabited the contiguous mountain region that falls under the southeastern part of modern Turkey, the north and eastern part of Iraq, the northeastern part of Syria and the northwestern part of Iran for about 3,000 years (or longer, as some historians insist), retaining their own language, customs and culture. These parts were created on two different occasions: first in 1514 when Kurdistan was divided between the Ottoman and Persian empires following the battle of Chaldiran;1 secondly between 1920 and1923 when Britain and France further altered the political contours of Kurdistan by dividing Ottoman Kurdistan among Iraq, Iran, Syria and Turkey (Meho and Maglaughlin 2001: 3). A fierce and independent collection of wild mountain tribes, they had ferociously defended their terrain and somehow managed to survive the succession of conquering armies including Assyrians, Persians and Greeks that marched and countermarched across Anatolia and Mesopotamia over the centuries. Prior to World War I, Kurdish territories were divided between the Persian and the Ottoman Empires. In order to maintain their exploitation in the colonised areas, the colonising powers, especially the British, resorted to the divide-and-rule strategy pitting one ethnic group against the other. This policy heightened ethnic conflict and fragmentation. The world system as an externally activating variable has played a critical role in politicising ethnic differences and the resulting political conflicts. The British imperialism provoked Kurdish nationalist aspirations for an independent Kurdistan but pitted Armenians and Kurds against each other to block its actualisation. Since the goal of imperialism was to appropriate the oil fields of the Kurds in the south, the creation of a centralised neo-fascist and imperial state was the critical solution.

Immediately after World War I, President Woodrow Wilson’s support for the principle of national self-determination for the non-Turkish nationalities living under the Ottoman Empire gave impetus to the Kurds. The Versailles Peace Conference of 1919 provided the first forum where Kurdish national aspirations were acknowledged by the international community; but, this acknowledgement proved to be short-lived. Upon the breakup of the Ottoman Empire, an ancient race composed of tribes, tribal confederations and feudal groups with martial traditions were promised for the first time in their long history an independent state in their own mountainous homeland under the Treaty of Sevres of August 10, 1920 (Eagleton 1963: 11-12; Chaliand 1980: 8-10). However, a vigorous nationalist uprising under the Turkish leader Mustafa Kemal Ataturk forced the Allies to accept a revised agreement—the Treaty of Lausanne 1923—which omitted all references to an autonomous or independent Kurdish state. The Sevres–Lausanne period presented what might be called a tragic incident in the Kurdish struggle and aspirations. Moreover, the Treaty of Sevres and the creation of new boundaries leading to the distribution of the Kurds among several countries—Turkey, Iran and Iraq—further complicated Kurdish plans. As a result, the Kurds became a stateless minority in the region.

Traditionally, Kurdish life was nomadic, revolving around sheep and goat-herding throughout the Mesopotamian plains, the highlands of Turkey and Iran. Although the Kurds lived in Kurdistan for centuries, they never had a state of their own nor had formed an independent political entity. In the modern times, they achieved two short-lived semi-independent entities: the Kingdom of Kurdistan in Iraqi Kurdistan under Sheikh Mahmoud (1922–1924) and the Mahabad Republic under Qazi Mohammed (January–December 1946), which is now Iranian Kurdistan. Throughout their history they have been ruled by outsiders including Armenians, Persians, Byzantines and later the Turks and Arabs.

Since the end of the First World War, when the great powers imposed their ill-suited solutions to the problems of West Asia, the Kurdish people have constantly suffered from various forms of national oppression in each of the newly constituted states. In some cases this oppression was brutal, as in Kemalist Turkey, while in others it was cunning, like the suppression in Iran. Iraq, on the other hand, has allowed the existence of a Kurdish nationality; it has allowed a limited use of Kurdish language and provided for at least a nominal degree of autonomy to the Kurdish-inhabited areas which also has included a policy of Arabisation involving the mass deportation of Kurds and implantation of Arabs on their lands.

Origins of the Kurds

One of the first mentions of Kurdistan in the historical records appears in cuneiform in the Sumerian and Assyrian inscriptions of 2000 BC, which refer to it as the ‘land of the Karda’ in the Zagros-Taurus Mountains of the northern and northeastern parts of Mesopotamia. The Babylonians called the inhabitants of ‘Karda’ as ‘Gardu’ and ‘Qarda’. In the neighbouring area of Assyria to the south, they were known as ‘Qurti’ or ‘Guti’. When the Greeks entered this territory, they referred to these people as either ‘Kardukh’, ‘Carduchi’ or ‘Gordukh’. The Armenians called the Kurds ‘Gortukh’ or ‘Gortai-kh’ and the Persians knew them as ‘Gord’ or ‘Kord’. In Hebrew and Chaldean languages they were respectively referred to as ‘Qardu’, ‘Kurdaye’ and ‘Qurdaye’ (Izady 1992: 31). The modern form ‘Kurd’ first appeared in the Arabic writings of the ninth century AD with the plural form ‘Akrad’ (Elphinston 1946: 92).

In the sixteenth century, after prolonged wars, Kurdish-inhabited areas were split between the Safavid2 and Ottoman Empires. A major division of Kurdistan occurred in the aftermath of the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514 and was formalised in the 1639 Treaty of Zuhab (Somel 2003: 306). As a result, western Kurdistan became part of the Ottoman Empire while eastern Kurdistan became part of Iran. However, prior to World War I most Kurds lived within the boundaries of the Ottoman Empire in the province of Kurdistan.

Many Kurdish historians, anthropologists and scholars assert that the Medes3 are the ancestors of the Kurds. Scholars are on unsure ground when trying to establish the definite early origins of the Kurds. There are two favoured hypotheses: either the Kurdish people have sprung from the Iranian tribes that had immigrated into the Zagros mountains in the pre-historic times and had established themselves there or from those Iranian tribes migrating west that had imposed themselves on an autochthonous people and have exploited them ever since (Pelletiere 1984: 20-21).

Many Kurds are the descendents of several ancient peoples, mainly Iranian. They include Caucasian strains in the north and some Semitic strains in the south. They are however, bound together by a purely Kurdish influence which probably derives from the original mountain tribes which have inhabited these regions from the earliest times.

Kurdistan’s Physical Geography

Kurdistan lies at the mountainous transition belt of the Fertile Crescent with the Taurus and Zagros mountains forming an arc encircling the Mesopotamian region. The mountain chains of Iraqi Kurdistan run in a northwest to southeast direction along the border territories with Iran and Turkey. The territory of Kurdistan has no recognised international boundaries and even internal administrative boundaries within states are sometimes controversial and commonly ephemeral. This problem was compounded by the normative viewpoints of neighbouring states refusing to acknowledge the existence of a contiguous Kurdish geographical entity or as in the case of Turkey, the denial of the existence of Kurds as a distinct and discrete people and culture. The Kurds have a legitimate and possessive claim to a vast homeland that consists of roughly 2,00,000 square miles—an area equal to France, or slightly smaller than the state of Texas (Manafy 2005: 5).4

Figure 1.1 Kurdish Areas

Source: Dahlman, Carl (2002) “Political Geography of Kurdistan”, Eurasian Geography and Economics, 43(4): 284.

Kurdistan is an oasis in a water-starved region. The abundant rainfall, which is common over the Zagros and Taurus mountains, has made Kurdistan one of the few watersheds of West Asia; it is home to the source of two major river systems in the world—the Tigris and Euphrates.

Economy

Kurdistan is known to be very rich in its natural resources. Not only oil and water, but also copper, chromium, iron and sulphur are found in abundance in the Kurdish soil. Kurdistan’s wealth of high-grade pasture lands has long made it suitable for a pastoralist economy, but it is equally suitable in many areas for intensive agriculture. The rich pastures have always ensured that in all historical periods, regardless of how dominant the agriculture sector may have been, there have been nomadic herdsmen exploiting them to their fullest.

Despite the huge economic production of Kurdistan whether from its natural resources or agriculture goods, only a small portion of its benefits is geared towards the local population. Moreover, modern heavy industries in Kurdistan are almost non-existent. After the fall of Saddam Hussein, Iraqi Kurdistan has attracted foreign investment especially in the oil sector (Torchia 2007). It is true that oil is produced in abundance from the Kurdish areas; nevertheless, skilled labourers are entirely non-Kurds. Kurdistan has among the largest oil reserves in West Asia. According to various studies, Kurdistan sits on 43.7 billion barrels (bb) of proven oil and 25.5 bb of potential reserves. In addition, the majority of the estimated 200 trillion cubic feet of gas in Iraq is reported to be in the Kurdistan region.5 However, both in Iran and Iraq, the oil and gas sub-sectors were particularly hard-hit by the war, with much of the infrastructure destroyed. These sub-sectors were and are the primary source of the income from foreign exchange.

A special factor of the Kurdish economy is that it does not constitute one entity but is split among several countries. The individual parts are isolated from one another and each part is dependent on the economy of its ruling state. Nevertheless, the mountainous borders of Kurdistan are practically beyond control, and for this reason, contraband trade is widespread—particularly between the Iranian and Iraqi Kurdistan. The countries controlling Kurdistan are economically linked to the industrialised countries and the different parts of Kurdistan are in turn dependent on their respective central governments—a unique situation which might explain why economic progress is so irregular and disproportionate. Kurdistan constitutes the marginal areas of these countries; therefore, it is also underdeveloped. Looking at vital statistics, it is always what the central government wants the people to know, which is not always the reality. Healthcare, educational facilities and last but not the least, job opportunities are not available to their Kurdish minorities unless they go through the assimilation process. In Turkey, everything is dependent on how well a Kurd is assimilated in the political economy (Leezenberg 2000: 3).

Kurdish Population, Society and Stratification

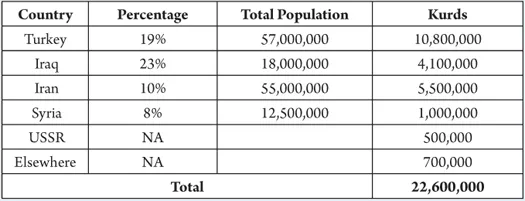

Stephen C. Pelletiere asserted that in Kurdistan, tribalism and nomadic life have been largely replaced by a growing feudalism and a semi-capitalistic development. However, the Aghas, who were encouraged by the British to secure and privatise tribal lands, still command Kurdish loyalty in some parts of Kurdistan and in the remote and primitive regions of Kurdistan tribalism still persists (Pelletiere 1984: 18). Kurdish society is highly stratified, where tribal elites dominate the settled peasants. Conflicts between the tribes and exploitative relations between the dominant and subject strata have long divided Kurdish society. Conflicting interests have always prevented collective action. Furthermore, there are various non-Kurdish minorities living among the Kurds and tied to them by intricate networks of social and economic relations. In terms of numbers, the estimates of Kurdish population vary (see Table 1.2 for population estimates). Kurdish nationalists are tempted to exaggerate the number; governments of the region minimise it. Although there are no official censuses regarding the number of the Kurds, most sources agree that there are more than 30 million Kurds and at least one-third of them live outside Kurdistan because of war, forced resettlements or economic deprivation.

Pelletiere (1984) approximates the Kurdish population in Turkey, Iran, Iraq, Syria and the former Soviet Union to be between 7 and 7.5 million. A breakdown of this figure illustrates the following: 3 million in Turkey, approximately 2 million in Iran and 2 million in Iraq and a very small number of Kurds in Syria and the former Soviet Union. See the distribution of the Kurdish population:

Table 1.2 Population Estimates for Kurds, 1991*

*Estimates in round numbers

Source: Adopted from McDowall, David (1992), The Kurds: A Nation Denied, London: Minority Right Publications, 2.

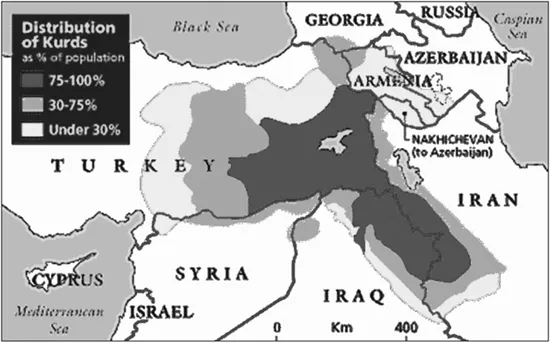

Fig. 1.3 Kurdistan Identified by Population Distribution

Source: http://www.iranreview.org/content/Documents/Kurds-A-Comman-Issue-for-Iran-Turkey.htm

Yavuz and Gunter (2001) approximate the Kurdish population in Turkey as 7 million (making up between 12 to 15 percent of the population), 6 million in Iran (11 percent), 3 million in Iraq (between 20 to 23 percent) and 8,00,000 in Syria (7 percent). There are also large concentrations of Kurds in Germany (over 50,000), Israel (over 1,00,000) and Lebanon (75,000–1,00,000). Australia, Canada, England, Finland, France, Greece, Sweden and the United States each have a Kurdish population of over 10,000 (Meho and Maglaughlin 2001: 3). The Kurds are largely Sunni Muslims divided tribally, geographically, politically, linguistically, religiously and ideologically. However, the accuracy of the Kurdish population estimates is difficult to determine. They are the third largest ethnic group in the region after the Arabs and Persians.

Several factors have contributed to the Kurds’ isolation in the mountainous terrain that formed a geographical and cultural barrier between them and their neighbours. These factors include their ferocity in defending their own territory and their largely self-sufficient economy which reduced their dependence on outsiders. The fact that most Kurdish areas are remote and inaccessible has fostered the independence of even the small villages. The scarcity of arable land and pastoral range lands increases the struggle for water and pasture. The village isolation in their tribe-oriented and class-ridden society has remained very strong despite modern influences. The Kurds lived in a variety of settings as urban dwellers but the vast majority lived in small villages. The numbers of nomads and semi-nomads steadily decreased; although, that way of life still exists. Small working class and middle-class groups have begun to emerge in the cities but in most rural areas the basic form of social and political organisations are still based on descent, clans and ownership of land. In the villages, leaderships are divided between the mir or beg, who leads the tribe (or the agha who leads one of the clans that form a tribe) and the sheikhs or mullahs who are the religious leaders.

There were other major divisions within Kurdish society. A basic distinction was between tribal and non-tribal Kurds. In principle, most Kurds belonged to one or the other of the many tribes, defined by Chaliand as ‘a territorially fixed social and economic unit founded on real or imagined blood ties which give the group its structure.’ But not all were tribal by the twentieth century; many lived in towns or had become tenants or labourers on land in the plains. By 1918, many Kurds had chosen to live in Kurdistan having taken service with the Ottoman government in the army or civil services (Chaliand 1994: 19). For sheer survival, smaller tribes had to ally themselves with larger ones or with each other or enter into federations which in turn dissolved or changed in composition dictated by the fortunes of war and other circumstances. Tribes were subdivided into clans and groups of families; each always being on the defensive— even suspicious of the others. Each man owed complete allegiance to his family and tribe and to the tribal sheikh, who settled disputes in accordance with the Islamic and tribal laws and Kurdish customs.

The cohesion of the Kurdish tribe is based on a mixture of blood ties and territorial allegiances associated with strong religious loyalties. Beyond the tribe, many Kurds, especially those who lived in the rural areas, occasionally showed loyalty to a nation, s...