- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Artificial Intelligence, Cybersecurity and Cyber Defence

About this book

The aim of the book is to analyse and understand the impacts of artificial intelligence in the fields of national security and defense; to identify the political, geopolitical, strategic issues of AI; to analyse its place in conflicts and cyberconflicts, and more generally in the various forms of violence; to explain the appropriation of artificial intelligence by military organizations, but also law enforcement agencies and the police; to discuss the questions that the development of artificial intelligence and its use raise in armies, police, intelligence agencies, at the tactical, operational and strategic levels.

Information

1

On the Origins of Artificial Intelligence

1.1. The birth of artificial intelligence (AI)

1.1.1. The 1950s–1970s in the United States

Alan Turing’s article, published in 1950 [TUR 50], which is one of the founding works in the field of AI, begins with these words: “I propose to consider the question, ‘Can machines think?’”

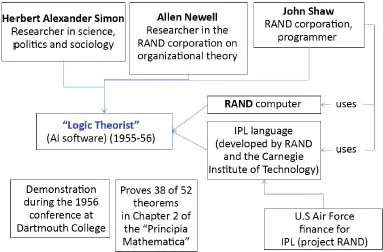

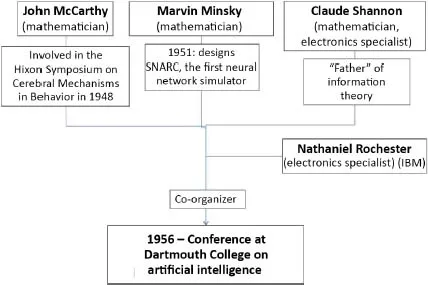

In 1955, “Logic Theorist”, considered to be the first AI program, was developed. This work was the result of cooperation between three researchers: a computer scientist (John Shaw) and two researchers from the humanities and social sciences (Herbert Simon and Allen Newell) [SIM 76]. The application was programmed using IPL language [STE 63], created within the RAND and the Carnegie Institute of Technology1 (a project that received funding from the US Air Force). Here we have the essential elements of AI research: a multidisciplinary approach, bringing together humanities and technology, a university investment and the presence of the military. It is important to note that although the program is described today as the first AI code, these three researchers never use the expression “artificial intelligence” or present their software as falling into this category. The expression “artificial intelligence” appeared in 1956, during a series of seminars organized at Dartmouth College by John McCarthy (Dartmouth College), Claude Shannon (Bell Telephone Laboratories), Marvin Minsky (Harvard University) and Nathaniel Rochester (IBM Corporation). The aim of this scientific event was to bring together a dozen or so researchers with the ambition of giving machines the ability to perform intelligent tasks and to program them to imitate human thought.

Figure 1.1. The first artificial intelligence computer program “Logic Theorist”, its designers, its results

Figure 1.2. The organizers of a “conference” (two-month program) at Dartmouth College on artificial intelligence in 1956

While the 1956 conference was a key moment in AI history, it was itself the result of earlier reflections by key players. McCarthy had attended the 1948 Symposium on Cerebral Mechanisms in Behavior, attended by Claude Shannon, Alan Turing and Karl Lashley, among others. This multidisciplinary symposium (mathematicians, psychologists, etc.) introduced discussions on the comparison between the brain and the computer. The introduction of the term “artificial intelligence” in 1956 was therefore the result of reflections that had matured over several years.

The text of the proposal for the “conference” of 19562, dated August 31, 1955, submitted for financial support from the Rockefeller Foundation for organizing the event, defines the content of the project and the very concept of artificial intelligence:

“The study is to proceed on the basis of the conjecture that every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it. An attempt will be made to find how to make machines use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans, and improve themselves.”

The project was more successful than expected because 10 people did not participate, but 43 (not including the four organizers)3, including Herbert Simon and John Nash. This audience was composed almost entirely of North Americans (United States, Canada), and two British people. In any case, it was entirely Anglophone.

In an article titled “Steps toward artificial intelligence” [MIN 61], Marvin Minsky described, in 1961, these early days of AI research and its main objectives:

“Our visitor4 might remain puzzled if he set out to find, and judge these monsters for himself. For he would find only a few machines (mostly ‘general-purpose’ computers, programmed for the moment to behave according to certain specifications) doing things that might claim any real intellectual status. Some would be proving mathematical theorems of rather undistinguished character. A few machines might be playing certain games, occasionally defeating their designers. Some might be distinguishing between hand-printed letters. Is this enough to justify so much interest, let alone deep concern? I believe that it is; that we are on the threshold of an era that will be strongly influenced, and quite possibly dominated, by intelligent problem-solving machines. But our purpose is not to guess about what the future may bring; it is only to try to describe and explain what seem now to be our first steps toward the construction of ‘artificial intelligence.’”

AI research is structured around new laboratories created in major universities. Stanford University created its AI laboratory in 1963. At MIT, AI was handled within the MAC project (Project on Mathematics and Computation), also created in 1963 with significant funding from ARPA.

From the very first years of its existence, the Stanford AI lab has had a defense perspective in its research. The ARPA, an agency of the US Department of Defense (DoD), subsidized the work through numerous programs. The research topics were therefore influenced by military needs, as in the case of Monte D. Callero’s thesis on “An adaptive command and control system utilizing heuristic learning processes” (1967), which aimed to develop an automated decision tool for the real-time allocation of defense missiles during armed conflicts. The researcher had to model a missile defense environment and build a decision system to improve its performance based on the experiment [EAR 73]. The influence of the defense agency grew over the years. By June 1973, the AI laboratory had 128 staff, two-thirds of whom were supported by ARPA [EAR 73].

This proximity to the defense department did not, however, condition all its work. In the 1971 semi-annual report [RAP 71] on AI research and applications, Stanford University described its prospects as follows:

“This field deals with the development of automatic systems, usually including general-purpose digital computers, that are able to carry out tasks normally considered to require human intelligence. Such systems would be capable of sensing the physical environment, solving problems, conceiving and executing plans, and improving their behavior with experience. Success in this research will lead to machines that could replace men in a variety of dangerous jobs or hostile environments, and therefore would have wide applicability for Government and industrial use.”

Research at MIT in the 1970s, although funded by the military, also remained broad in its scope. Presenting their work to ARPA in 1973, the researchers felt that they had reached a milestone that allowed them to envisage real applications of the theoretical work carried out until then. But these applications cannot be reduced to the field of defense alone:

“The results of a decade of work on Artificial Intelligence have brought us to the threshold of a new pha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Title page

- Copyright

- Introduction

- 1 On the Origins of Artificial Intelligence

- 2 Concepts and Discourses

- 3 Artificial Intelligence and Defense Issues

- Conclusion

- Appendices

- Appendix 1: A Chronology of AI

- Appendix 2: AI in Joint Publications (Department of Defense, United States)

- Appendix 3: AI in the Guidelines and Instructions of the Department of Defense (United States)

- Appendix 4: AI in U.S. Navy Instructions

- Appendix 5: AI in U.S. Marine Corps Documents

- Appendix 6: AI in U.S. Air Force Documents

- References

- Index

- End User License Agreement

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Artificial Intelligence, Cybersecurity and Cyber Defence by Daniel Ventre in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Computer Science General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.