Studies in Archaeological Conservation

- 268 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Studies in Archaeological Conservation

About this book

Studies in Archaeological Conservation features a range of case studies that explore the techniques and approaches used in current conservation practice around the world and, taken together, provide a picture of present practice in some of the world-leading museums and heritage organisations.

Archaeological excavations produce thousands of corroded and degraded fragments of metal, ceramic, and organic material that are transformed by archaeological conservators into the beautiful and informative objects that fill the cases of museums. The knowledge and expertise required to undertake this transformation is demonstrated within this book in a series of 26 fascinating case studies in archaeological conservation and artefact investigation, undertaken in laboratories around the world. These case studies are contextualised by a detailed introductory chapter, which explores the challenges presented by researching and conserving archaeological artefacts and details how the case studies illustrate the current state of the subject.

Studies in Archaeological Conservation is the first book for over a quarter of a century to show the range and diversity of archaeological conservation, in this case through a series of case studies. As a result, the book will be of great interest to practising conservators, conservation students, and archaeologists around the world.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Introduction

INTRODUCTION

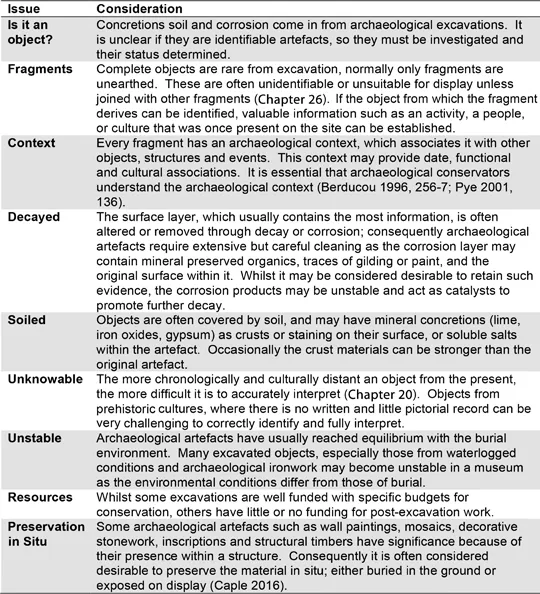

The nature of archaeological artefacts

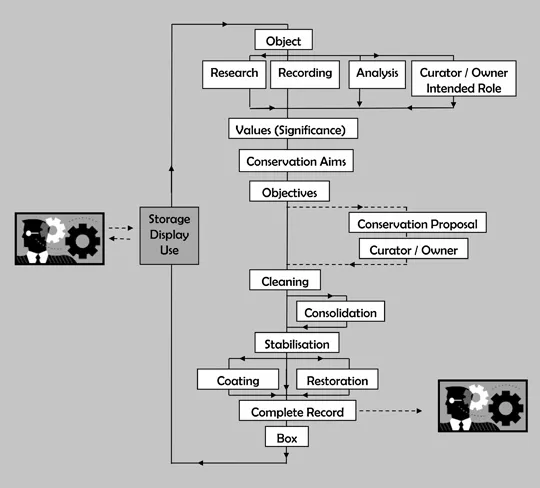

The conservation process

The organisation of archaeological conservation in practice

- Museum collections: Large number of complete objects which primarily have a display and education function. The objects usually already have a known date, culture and function, consequently, conservation work focuses on cleaning, reassembly and restoration of the artefacts for display. In large museums, conservators may work in specialist collection areas and develop considerable skills dealing with specific materials. In smaller museums, a single conservator may work on a range of materials and so requires a more varied range of skills and experiences.

- Large-scale research excavations: These invariably take place on sites of a known date and aim to solve research questions and reveal remains for future display. They unearth objects, which have, through their stratigraphy and associations with other objects and structures, the potential to contribute to our understanding of the past. This information may change the existing perceptions about the date, cultural associations, and use of specific objects. Such high potential archaeological (evidential) value (as well as the fragility and instability of the objects) justifies the costly presence of a conservator on large excavations. Typically, conservators on excavations need the skills to deal with a wide range of materials, especially in on-site conditions. Familiarity with the archaeological process is important.

- Cultural resource management: In countries with commercial archaeology organisations, there are often many small excavations ahead of development; the date, extent, and nature of the site is often initially unknown. The number of artefacts unearthed and their archaeological value, which depend on the stratigraphy, structures, and associations, will often not be known until after the excavation has been completed. In such circumstances, heritage agencies normally build in an assessment phase, where the excavation records, excavated artefacts, historical information, etc. are assessed, and the level of post-excavation resources assigned depends on the assessed value.5 This means that the archaeological conservator normally undertakes a large volume of initial assessment work, e.g. X-radiography, packaging, and storage of a large quantity of freshly excavated material, and only undertakes conservation work on a selected group of o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- PART I Introduction

- PART II Case studies: stone and plaster

- PART III Ceramics and glass

- PART IV Metals

- PART V Organics – wood, textiles, leather

- PART VI Bone, composites and display

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app