A Guide to the Formulation of Plans and Goals in Occupational Therapy

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

A Guide to the Formulation of Plans and Goals in Occupational Therapy

About this book

This practical guide for occupational therapists introduces a tried and tested method for moving from assessment to intervention, by formulating plans and measurable goals using the influential Model of Human occupation (MOHO).

Section 1 introduces the concept of formulation – where it comes from, what it involves, why it is important, and how assessment information can be guided by theoretical frameworks and organised into a flowing narrative. Section 2 provides specific instructions for constructing occupational formulations using the Model of Human Occupation. In addition, a radically new way for creating aspirational goals is introduced - based on a simple acronym - which will enable occupational therapists to measure sustained changes rather than single actions. Section 3 presents 20 example occupational formulations and goals, from a wide range of mental health, physical health and learning disability settings, as well as a prison service, and services for homeless people and asylum seekers.

Designed for practising occupational therapists and occupational students, this is an essential introduction for all those who are looking for an effective way to formulate plans and goals based on the Model of Human Occupation.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part I Understanding the concept of a formulation

1 Where does the idea of formulation come from?

A brief history

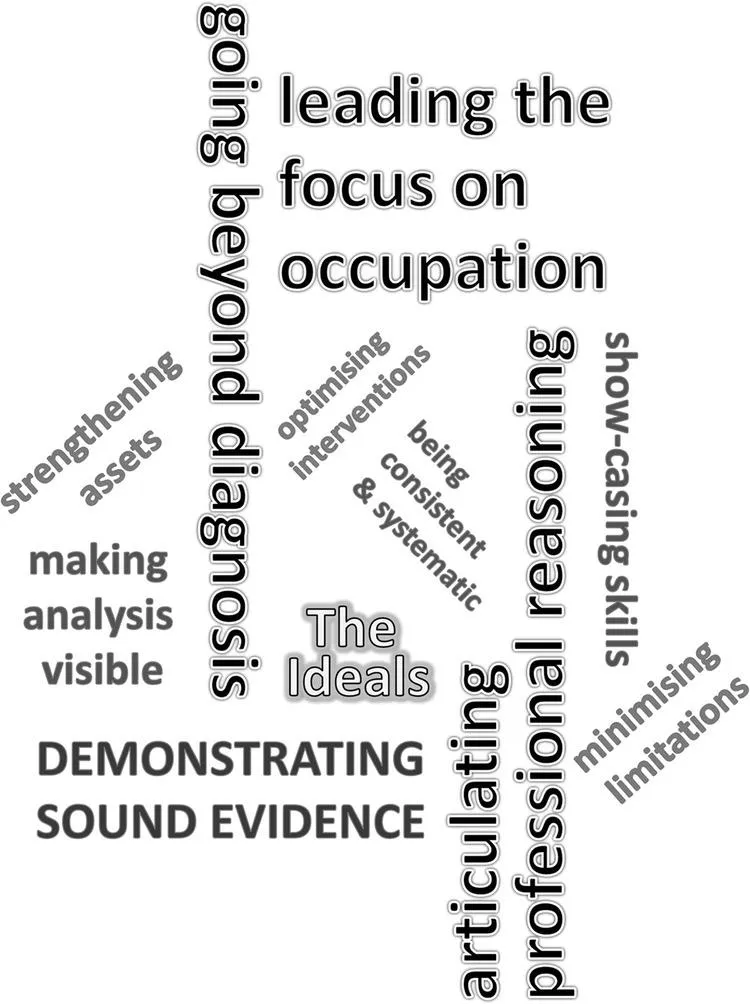

‘in relation to assets and liabilities in social adaptation, activities of daily living adaptation, and disease adaptation … [supporting] the philosophy that occupational performance may be improved by strengthening assets as well as minimizing liabilities’ (Rogers 1982)

‘The challenge for all occupational therapists is to make the invisible reasoning processes visible through the appropriate use of profession-specific language in discourses, assessments, reports, outcome measures, presentations and conversations, so that sound evidence is shown to underpin occupational therapists’ visible practice’ (p747)

References

- Brooks R, Parkinson S (2018) Occupational formulation: a three-part structure. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 81(3), 177–179.

- Carrier A, Levasseur M, Bédard D, Desrosiers J (2010) Community occupational therapists’ clinical reasoning: identifying tacit knowledge. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 57(6), 356–365.

- Connell C (2015) An integrated case formulation approach in forensic practice: the contribution of occupational therapy to risk assessment and formulation. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 26(1), 94–106.

- Cubie SH, Kaplan K (1982) A case analysis method for the Model of Human Occupation. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 36(10), 645–656.

- Eells T (2001) Update on psychotherapy case formulation research. The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 10(4), 277–281.

- Forsyth K (2017) Therapeutic reasoning: planning, implementing, and evaluating the outcomes of therapy. In: RR Taylor ed. Kielhofner’s Model of Human Occupation: Theory and Application. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. 159–172.

- Forsyth K, Mann LS, Kielhofner G (2005a) Scholarship of practice: making occupation-focused, theory-driven, evidence-based practice a reality. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(6), 260–267.

- Jamieson L, Parkinson S (2017) Unlocking potential: case formulation and measurable goals in a prison setting. Occupational Therapy News, 25(3), 36–38.

- Lee E, Toth H (2016) An integrated case formulation in social work. Towards developing a theory of a client. Smith...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Lists of figures

- List of tables

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part I: Understanding the concept of a formulation

- Part II: Constructing occupational formulations and goals

- Part III: Example occupational formulations and goals

- Outline of the range of occupational issues in example occupational formulations

- Index