- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Peace and Conflict in Africa

About this book

Nowhere in the world is the demand for peace more prominent and challenging than in Africa. From state collapse and anarchy in Somalia to protracted wars and rampant corruption in the Congo; from bloody civil wars and extreme poverty in Sierra Leone to humanitarian crisis and authoritarianism in Sudan, the continent is the focus of growing political and media attention.

This book presents the first comprehensive overview of conflict and peace across the continent. Bringing together a range of leading academics from Africa and beyond, Peace and Conflict in Africa is an ideal introduction to key themes of conflict resolution, peacebuilding, security and development. The book's stress on the importance of indigenous Africa approaches to creating peace makes it an innovative and exciting intervention in the field.

This book presents the first comprehensive overview of conflict and peace across the continent. Bringing together a range of leading academics from Africa and beyond, Peace and Conflict in Africa is an ideal introduction to key themes of conflict resolution, peacebuilding, security and development. The book's stress on the importance of indigenous Africa approaches to creating peace makes it an innovative and exciting intervention in the field.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Peace and Conflict in Africa by David Francis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Peace & Global Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

Peace & Global Development1 | Introduction: understanding the context of peace and conflict in Africa

Africa: context of peace and conflict

For most of the post-colonial history of Africa peace has remained elusive. Peace and development have proved far more difficult and complex to achieve than the Afro-optimists envisaged in the immediate post-independence period, owing to a range of domestic and external factors. Two contrasting iconic images have dominated the public, if not the global, perception of Africa. First, the image of the dangerous and mysterious Africa as represented by perennial violent wars and bloody armed conflicts, perpetual political instability, unrelenting economic crises, famine, disease and poverty – all symbolizing the ‘hopeless continent’ and the African predicament. Second, the wildlife safari and the Hollywood film industry image of Africa. This is represented by the rise of tourism and increase in popularity of the wildlife safari on the continent, and its portrayal by National Geographic magazine pictures and Hollywood movies in terms of extremes, i.e. of a romanticized place where lions, elephants and giraffes roam freely in a state of nature – e.g. The African Queen (1951), Out of Africa (1985) and The Lion King (1994) – but at the same time a dangerous, mysterious and exotic continent – e.g. Dogs of War (1980), Black Hawk Down (2001) and Blood Diamond (2006). These contrasting representations of Africa have not only been instrumental in shaping and reinforcing public perceptions about the continent, but have also legitimized the dominant worldview of a ‘tragic continent’ and a ‘basket case’. It is therefore not surprising that the greater part of the media news coverage of Africa reflects the sensational and stereotypical presentations of the continent. According to Robert Stock, ‘Africa’s success stories have generated little media interest. The Western media’s negative stereotyped reporting of African events have been instrumental in convincing the Western public as well as politicians, that Africa is a hopeless case’ (Stock 2004: 35).1 To some extent, therefore, this dominant presentation of the continent by the international media is possible only because Africa is not only the poorest region of the world but also the ‘least-known continent’ in the twenty-first century (ibid.: 6, 15).

These dominant presentations not only give the impression that Africa is a homogenous continent, but also fundamentally constrain our understanding of the nature, dynamics and complexities of peace and conflict in Africa. There are two common stereotypes used to convey the notion of a homogenous continent. First, ‘Africa as a country’, which depicts and describes the entire continent as a single country.2 C. P. Eze’s recent book Don’t Africa Me (2008) rejects the stereotypical presentation and tendency to homogenize the continent as if it were a single country. Second is the perception of Africa as a single region, not only in terms of continental size but more so in subregional terms, whereby there is no differentiation between what is often described as the ‘five Africas’, i.e. West, southern, East and Central, Horn and Maghreb North. These stereotypes and simplified depictions mask the important fact that Africa is a diverse, heterogeneous and complex continent, and this is reflected in its various peoples, cultures, ecological settings, historical experiences, and political and socio-economic geographies. Hence, one can safely talk about ‘not one but many Africas’ (Chazan et al. 1999: 14). As a dynamic continent, and since the pre-colonial era, Africa has been marked and transformed by certain dominant trends, patterns and influences, including strong, viable and developed pre-colonial empires and indigenous civilizations, slavery, colonialism, imperialism, decolonization and neocolonialism, cold war politics, post-colonial patrimonial states, and contemporary wars and armed conflicts. But a dominant feature of contemporary Africa is the trajectory of simultaneous advancement and reversal at both continental and regional levels. What is more, Africa in the first decade of the twenty-first century is very different from the Africa of the mid-twentieth century. The pattern of continuity and change remains a dominant feature of the continent.

Therefore, to understand the context of Africa and African politics and how this creates the conditions for wars and armed conflicts, insecurities and under-development, and the possibilities for peace and non-violent conflict transformation, we have to start with the ‘dehomogenization’ of African politics, i.e. the appreciation that we are not talking about a single, monolithic, homogenous and static sociocultural, political, economic, behavioural and attitudinal pattern of governance (Charlton 1983: 32–48). Despite the diversity and heterogeneity of the continent and African politics, however, there are also commonalities in terms of the dominance of the state and patterns of domestic politics based on neo-patrimonialism, excessive levels of external dependence, the rural–urban divide and the predominance of a rural population, and what Naomi Chazan et al. described as the ‘Africanisation and localisation of politics’ (1999: 14).

What does this analysis say about the context of contemporary Africa in relation to the problems and challenges of peace and conflict? Africa is a resource-rich continent and one of the most resource-endowed in the world. Of the twenty-one known minerals, the top five in terms of exports are crude oil, other petroleum products, natural gas, diamonds and coal. To illustrate its resource abundance, Africa produces an estimated 10 million barrels of oil per year, and its total share of world crude oil production is about 12 per cent. Nigeria, a leading oil producer, accounts for more than a quarter of Africa’s oil production. In addition, Africa accounts for 18 per cent of the world’s liquefied natural gas. Africa’s abundant mineral and human resources, and the enormous wealth they produce, have not, however, translated into poverty reduction, long-term economic growth, increased livelihood or welfare for the majority of Africans. This paradox of ‘poverty amidst plenty’, and what some analysts describe as the ‘natural resource curse’, is largely due to bad management of natural resources by corrupt ruling and governing elites, state weakness and a range of external factors (African Development Bank 2007: xv–xix).3 With the end of the cold war there has been renewed international interest in Africa’s natural resources because of the threats to global energy resources and competition posed by the new emerging economic powers of China and India. According to the president of the African Development Bank, Donald Kaberuka,

The rekindled interest in Africa’s resources is largely driven by global economic growth, especially in Asia, and the related demand for fossil fuels and minerals. This situation raises questions: how the continent can best leverage its resources for its development given the complexities and trade-offs. Indeed, the market demand for Africa’s natural resources is strong and growing; but Africa needs these resources too for its own development. (ibid.: iii)

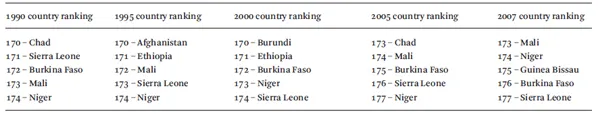

What have been the consequences of bad governance and mismanagement of Africa’s abundant resources? According to World Bank socio-economic and development indicators for sub-Saharan Africa, out of a population of 770.3 million (2006), the life expectancy at birth is 47.2 years. This is not surprising because only 44.4 per cent of all births are attended by skilled health staff.4 In addition, only 54.5 per cent (2000) of the total population have access to improved water sources, while 52.9 per cent (2000) of the urban population have access to improved sanitation facilities. While there has been some modest improvement in the economic growth rate for sub-Saharan Africa at 5.6 per cent (2006) annual GDP, the total military expenditure limits the human security impact of this economic growth rate because it accounts for 1.6 per cent (2005) of total GDP. In addition, though there has been a remarkable increase in foreign direct investment (FDI), with net inflows of US$16.6 billion (2005) and a further US$32.6 billion (2005) in Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) – both buoyed by China’s renewed ‘romance’ with Africa and the 2005 G8 aid commitment – long-term indebtedness is still a serious concern with a total of US$176.7 billion (2005) external debt and a total of 8.8 per cent (2005) of debt service on export of goods, services and income.5 Furthermore, the UNDP Human Development Index (HDI) ranking gives an interesting indication of the level of underdevelopment and insecurities prevalent in Africa. Between 1990 and 2007, Africa’s weak and failing states have dominated the bottom ten rankings of the HDI Low Human Development category. In fact, during the same period, two African countries have constantly been listed in the bottom three and ranked as the ‘worst place to live in the world’: Niger and Sierra Leone (see Table 1). In addition, global environmental problems and, in particular, the negative effect of climate change are set to adversely affect Africa. According to the African Development Bank Report (2007), by 2025 almost 50 per cent of Africans will be living in areas of water scarcity or water stress because of increasing depletion and scarcity of water resources. Though Africa accounts for the lowest greenhouse emissions of any continent, it is likely to bear the most disastrous consequences of climate change because of its ‘overdependence on natural resources and rain-fed agriculture, land degradation and the on-going deforestation process – compounded by widespread poverty and weak capacity for planning, monitoring and adaptation to the changes’ (ibid.: xviii).

TABLE 1.1 Human Development Index 1990–2007: bottom five countries

Sources: UNDP Human Development Reports, 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005 and 2007

In addition, political stability and governance indicators have been rather depressing. According to the Fund for Peace Failed States Index ranking for 2007, eight out of the top ten most unstable countries in the world are in Africa.6 The 2007 Transparency International Corruption Perception Index (CPI) lists seven African countries as part of the twenty countries ranked as highly corrupt, with Somalia ranked the second-most corrupt country in the world.7 Both the CPI and the Failed States Index are problematic, however, for several reasons. In particular, the Failed States Index uses three broad indicators (social, economic and political) to determine the level of instability or judge the ‘most critical cause of state failure’. The broad and specific indicators used to measure instability are difficult to quantify. Since this exercise is not ‘rocket science’, the index gives only an indication of the level of instability or cause of state failure, bearing in mind that these putative indicators are often clouded by political and hegemonic biases. For example, Sudan and the crisis in Darfur cannot be compared with what is globally acknowledged as the ‘chaos and mayhem’ that prevails in Iraq and Afghanistan. Yet these countries are ranked second (Iraq) and eighth (Afghanistan) in the Failed States Index.

Wars and armed conflicts have dominated the presentation and international media coverage of Africa because of the high incidence of political violence, and the frequency and multiplicity of wars and armed conflicts. According to the Uppsala University conflict database, Africa has had more wars and armed conflicts than any other region in the world. Based on the survey of conflicts by region between 1946 and 2006, Africa had the highest number of conflicts (74) in comparison to Asia (68), the Middle East (32), Europe (32) and the Americas (26).8 Based on this survey, the period 1990–2002 witnessed the intensification of wars and armed conflicts in Africa. This is not surprising because this period also witnessed the end of the cold war and its negative impact on the continent led to the emergence of what has been described as ‘post-Cold War wars’ in Africa, driven by the opportunities of neoliberal globalization (Francis 2006a: 80–85; Kaldor 1999; Duffield 2002).

But all these global indicators and indexes on Africa have one thing in common: the tendency to portray the continent as perpetually dangerous, undeveloped and ungovernable. In several ways, this reinforces the dominant international media presentation of Africa. In addition, these indicators and indexes fail to capture the contradictory trajectory of reversal and advancement that has come to define the continent at the dawn of the twenty-first century. Contrary to most of the conflict data on Africa, the reality is that deadly violence, wars and armed conflicts are on the decrease. Between 2000 and 2002, there were eighteen active wars and armed conflicts in Africa. As of February 2008, there were only five active wars and armed conflicts ongoing on the continent: Sudan (Darfur region), Kenya (post-election violence between December 2007 and February 2008), Somalia (excluding Somaliland), DR Congo (eastern region) and Chad. This decrease in wars in Africa is also reflected in the Uppsala University conflict database survey. The sharp decline in wars and armed conflicts indicates the level and intensity of African and international engagement in preventive diplomacy, conflict management and peacekeeping.

Based on the rather depressing socio-economic, development and governance indicators, some sections of the international community have been unanimous in the view that Africa will fail to meet any of the targets for the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) by 2015. According to the UN World Summit Declaration (2005): ‘Africa is the only continent not on track to meet any of the goals of the Millennium Declaration by 2015’.9 Given the fact that the MDGs have emerged as a development framework for the global governance institutions, international financial institutions (IFIs) and donor agencies in their development cooperation partnerships with Africa, and in particular low-income countries, the persistent presentation of Africa as being off track in meeting any of the targets raises some concerns. William Easterly argues that the ‘MDGs are poorly and arbitrarily designed to measure progress against poverty and deprivation, and […] their design makes Africa look worse than it really is’ (Easterly 2007: 2). Easterly agrees that Africa’s performance has been poor, but its ‘relative performance looks worse because of the particular way in which the MDGs’ targets are set’. Some scholars have been critical of the MDGs in relation to Africa and even question the efficacy of measuring or quantifying social and economic progress, the politics of target-setting and benchmarks that may be disadvantageous to certain regions. In addition, they argue that the goals themselves are far too ambitious and do not take into consideration the continent’s particular historical circumstances and development trajectory. They also question the link between increased aid and the likely attainment of the MDGs (ibid.: 1–22; Clement and Moss 2005; Charles et al. 2007: 735–51).

Is Africa a lost cause? Far from being a ‘tragic continent’ and a mere ‘basket case’, Africa’s peace and security challenges have emerged as a global concern and as rekindled international interest in the continent, as manifested by the ‘war on terrorism’ and the new predatory capitalist scramble (China and the West) for energy resources (oil and gas) in Africa. This unprecedented international focus on and engagement with Africa really took off in 2005 with former prime minister Tony Blair’s Commission for Africa as part of the UK’s EU and G8 presidency initiative to put the continent at the top of the international agenda. This has been followed by highly commercialized aid initiatives, fund-raising campaigns and high-profile adoption of African children by Hollywood celebrities, to the extent that some media commentators now allude to ‘Brand Africa’.10 To underscore the growing importance of Africa, in February 2007 President George Bush formally announced the establishment of the US Africa Command – AFRICOM – because ‘Africa is growing in military, strategic and economic importance in global affairs’. With a budget of US$75.5 million (1 October 2007–30 September 2008 fiscal year), AFRICOM will be responsible for US security in Africa.11 The renewed international focus on and engagement with Africa have brought to the fore the imperative for peace and conflict resolution on the continent as a prerequisite for democratic consolidation, political stability, social progress, long-term economic growth and sustainable development.

If this is the case, how do we provide a meaningful interpretation of politics and development in contemporary Africa, irrespective of the diversity and heterogeneity of the continent? The dominant interpretations and approaches to the study and understanding of African politics in the 1960s and 1970s have been modernization and dependency theories. These schools of thought have been the subject of many scholarly publications. This introductory chapter will therefore not attempt to recast the usual debates and interpretations.12 Against the background of the failure of both modernization and dependency theories to explain politics and development in post-colonial Africa, a new political economy interpretation emerged in the 1980s to provide an understanding of politics, underdevelopment, economi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- About the editor

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Table and figures

- Acknowledgements

- About the authors

- Abbreviations

- One | Understanding concepts and debates

- Two | Issues in peace and conflict in Africa

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index