![]()

Part One

Photographs Transformed into Socio-critical Paintings

![]()

1

Paintings Consolidating Fleeting Press Photos

The flow of news is occurring at an unprecedented speed in today’s accelerated world. News photos, made in split seconds, are constantly replaced by new ones. When these fleeting images become consolidated in slowly created paintings, the ensuing transformation has drastic consequences for the contents of both the painting and the photograph appropriated in the painting. Moreover, the perception of such artworks appears to be quite different from that of either a photograph or a painting.

If news photography tends to be considered as an accurate or truthful means of presenting the world, the paintings discussed in this chapter interrogate how the appropriated photographs represent reality. Moreover, paintings that integrate an adopted image through added-on painterly effects will normally require a larger effort on the part of the beholder. For instance, when a particular painting evokes associations with so-called action paintings as well as action photographs, this may prompt questions about the relationship between these two terms. Another example pertains to the materiality of news photos, which is commonly ignored in favor of their contents, but in paintings the corporality of the picture is much harder to ignore. Compared to the effort involved in our everyday scanning of news photos, a more sustained effort is needed to look at and interpret the decontextualized photographs and often somewhat blurred paintings discussed here. But these mental and visual exertions will also come with the reward of intriguing insights.

In particular since the 1960s, it has been quite a common strategy in modern and contemporary paintings to make explicit usage of photographs as main source. The appropriation of vernacular photography (such as family photography), images from commercials, or iconic photographs has produced different kinds of confrontational effects in the final paintings.1 In this chapter I focus on the appropriation of press photos by painters in their work. Although the fleetingness or informative function of such photos is often tied to social unrest or conflict, there is still much variety in the resulting paintings to be found. One painting in particular drew my attention because it deals in intriguing ways with the issues I intended to address. This painting, entitled Phienox, was created by the German artist Daniel Richter in 2000. In the course of this chapter I will explore how and what the strategy of incorporating press photos contributes to the meanings of this slowly made painting, and, vice versa, how this painting contributes to our understanding of the role of press photos. I will discuss Richter’s painting through comparison with several other, partly interrelated contemporary paintings and by organizing my argument around several key issues.

After introducing the painting by Daniel Richter, I critically consider some of the general consequences of adding the slow immediacy of painting to the fast immediacy of photography. In the next section, I discuss the results of the indirectness of the reproductive and multi-mediating process for paintings like that of Richter, followed by addressing several insights into the consequences of adding the corporality of paint to a photograph. This materiality of a painting contributes to its experience as “presence.” Quite differently, photographs, in their references to the past, often evoke associations with “absence.” In this context, I develop the argument that allusions to the history of painting and the genre of history painting relate to sociocultural memory, while news photos are usually experienced as a kind of presentness. Finally, I deal with the implications of decontextualizing news photos from their captions and journalistic reports for slow paintings. As it will become clear, the interrelated concerns all center on the dependency of the resulting paintings on the appropriated photographs when it comes to the meaning and interpretation of these paintings.

A recurring concept in the various sections is the notion of “simultaneous adaptation,” as defined by Lindiwe Dovey in her essay “Fidelity, Simultaneity and the ‘Remaking’ of Adaptation Studies” (2012). In her general definition, simultaneous adaptation means that two or more very different sources are incorporated in one adaptation, and that spectators are asked to draw parallels and create associations through a process of viewing. These diverse sources usually do not remain intact but are confronted in order to inflect or conflict with each other, thereby alluding to the complexities of our era of globalization.2 I will argue that the concept of “simultaneous adaptation,” as a critical, slowing-down factor in the creation and perception of the selected artworks, proves to be more useful for my discussion than several similar concepts, including “appropriation.”

Case Study of Daniel Richter’s Phienox (2000)

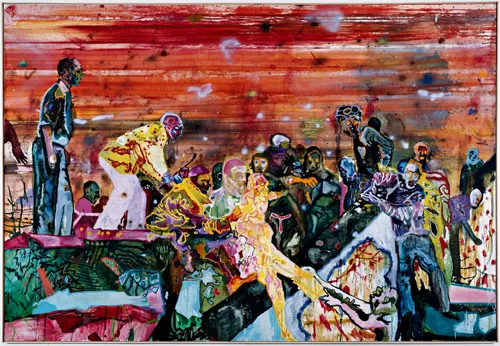

More than a dozen human figures are grouped in the foreground of a large painting before a bright red background, and in the center a yellow-colored body is lifted over a wall. This is the first impression of most spectators when approaching Daniel Richter’s painting Phienox (book cover and Figure 1.1). After that initial moment, however, the painting will only appear to raise more and more questions. A better understanding of what one is looking at will require some profound observation indeed. Although hardly any specific question related to the meanings in the painting will be definitively answered through mere contemplation, the image may invoke many different associations. It is easy to imagine various kinds of events being represented in the painting. The lifted body could be part of a tragedy or a liberation. Because the depicted event calls forth familiar images from newspapers and news websites, it is difficult to conclude to which particular news photo the painting refers. The bright colors of the skins of the figures make it difficult to link the scene to a specific ethnic group or a particular location. Closer inspection of the figures reveals that most heads look like skulls in X-ray photographs. Because so many of these associations are related to the fields of photography and other image recording technologies, as well as the history of painting, I selected Phienox as a case study that preeminently fits the issues discussed in this chapter.

Figure 1.1 Daniel Richter, Phienox, 2000, oil on canvas, 252 × 368 cm. Courtesy Deichtorhallen Hamburg/Sammlung Falckenberg. Photograph: Egbert Haneke © Daniel Richter c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2020.

To learn more about Richter’s sources for this work, it proved useful to consult published interviews with the artist, look up biographical information in catalogs, draw visual comparisons with his other paintings, and study analyses of his paintings by critics and scholars. But, as will become clear, such critical consideration gave rise to additional questions as well.

Daniel Richter was born in Hamburg in 1962. He also grew up there and became part of the left-wing radical punk movement when he was in his twenties. Sympathizing with the urban squatters, he started putting works of graffiti on surfaces in public spaces as part of their social protest. In so doing, urban graffiti artists can be said to have brought painting from the private spaces of studios and museums into the informal, public realm. It is easy to discern Richter’s skill at creating large wall paintings out of brightly colored contours and decorative patterns in Phienox. Most literally, a graffiti piece is applied to the wall at the center of the painting.

Not until he reached the age of thirty-one he decided to apply for admission to the study of visual arts at the Hochschule für bildende Künste in Hamburg. He explained his choice for the medium of painting in 1997 as “Painting is the most lethargic, slowest and most tradition-burdened medium and the hardest to expand. There, the challenge is greatest.”3 After scrutiny from up close, interestingly, the immediate association of Phienox with sketchy sprayed graffiti painting turns into an awareness of the rich diversity of small dynamic brushstrokes. In this respect, David Hughes has called Richter’s decision to focus on painting a political act in the form of a rejection of the ideology of technological progress.4 Considering his background in sociopolitical activism, it is quite surprising that Richter at first chose to make abstract paintings crowded with ornaments. As he explained in an interview with Philipp Kaiser, nonrepresentative painting attracted him as idea of radicalism and freedom.5 In 1998, Ulrike Rüdiger went as far as to link up Richter’s abstract paintings with increasingly violent inclinations in society, defining their images as battlefields of colors, forms, and styles.6

By 1999, Richter started inserting slightly distorted faces into his abstract paintings. Phienox, created one year later, is considered to be his first figurative painting. For his shift from abstract to figurative painting, he provided various reasons. One of them emerged from the need “to get closer to a present that I find unappetising. My need to express myself as a social being was so strong that I wanted to communicate it to others.”7

For this first figurative painting, Richter used news photos. In an interview he remarked that he was aware that when he first exhibited the painting in Berlin in 2000, just after the tenth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, visitors would think that he used news photos of that historical event. The photograph that he actually “appropriated,” however, was a press photo in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung taken after the bombing of the US embassy in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, in 1998.8 In more general terms, Richter said the following about the use of photographs (when discussing another painting): “I realized how little it takes to render a photo readable or unreadable. It basically depends on tiny details and poses, it being important to understand how much more these paintings have to do with an idea than with their appearance.”9 This claim, which actually addresses the immediacy of both photography and painting, will be discussed in more detail in the next section.

Hughes explained Richter’s preference for the medium of painting as a deliberate rejection of the ideology of technological progress, but this hardly implies that the artist was not interested in the increasing role of technology in today’s society. As he said in an interview with Andreas Hoffer and Mela Maresch, “The figures in my paintings arise from a disembodied view and from my interest in infrared heat, CCTV, night vision devices . . .”10 Through the painter K. P. Brehmer, one of his professors at the academy of arts, he learned about thermography (the recording of infrared heat). In thermography, heat-detecting cameras are employed to “photograph” the warmth emitted by bodies exposed to stimuli, resulting, as it were, in a scientific objectification of subjective inner experience. In fact, thermography records information from beneath the surface/skin of an object or human being.11 A quick search on the internet reveals many still and moving images of bodies made by means of thermography. The similarity with in particular the central figure in Phienox is striking: a flat pattern of yellow, orange, and red stains.

The striking bright shiny colors in ...