- 456 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This is a concise guide to the combined use of classical and molecular methods for the genetic analysis and breeding of fungi. It presents basic concepts and experimental designs, and demonstrates the power of fungal genetics for applied research in biotechnology and phytopathology. Case studies of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida albicans, Aspergillus niger, Neurospora crassa, Podospora anserina, Phytophthora infestans and others are included.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Biology of Fungi

Cees J. Bos

Wageningen Agricultural University, Wageningen, The Netherlands

Wageningen Agricultural University, Wageningen, The Netherlands

1. INTRODUCTION

Why do we study fungal genetics? Many fungi are excellent objects to study genetics, and genetics plays an important role in various fields of fundamental and applied mycology. In this chapter we consider some aspects of the biology of fungi that are essential for understanding genetic features and processes. In addition, various aspects of fungal genetics are reviewed in order to elucidate how they play a role in fundamental biology, biotechnology, plant pathology, and other fields of applied biology.

Fungi are lower eukaryotes, and most of them can be grown on defined media. That was the basis for the work of Beadie and Tatum [1], who made a new approach in the early 1940s to study genetic control of metabolism. Some fungi are obligate biotrophs (obligate parasites), such as the rust fungi and mildews. They can be grown only in conjunction with their host plant, but some stages can be studied in vitro. Genetic studies with these fungi have been done, although they are very laborious. They enable, however, the study of the genetics of such close host-parasite relations. In fact the rusts (Puccinia, Melampsora) provided the first proofs of a gene-for-gene relationship in host-parasite systems [2].

The most characteristic aspect of fungi is that they grow as a thread of cells (hypha) and are propagated by generative and/or vegetative spores. A spore germinates with a germ tube that grows only at the tip. Transverse cell wails (septae) are formed at some distance behind the tip except in Phycomycetes, which are coenocytic. In general, the septae have a pore that allows transport of cytoplasm, mitochondria, and even nuclei.

The top cell of a hypha often has more than one nucleus located at some distance from the tip. Several interesting studies on the growth of hyphal tips have been done, and this subject has an old tradition [3]. Soon after germination, hyphae will form branches, and the result is a network of hyphae (mycelium). Hyphal fusions (anastomoses) can occur at some distance from the tips. In principle they allow exchange of cytoplasm and also nuclei between hyphae of different origin leading to heterokaiyons (Chapter 4). A heterokaryon is a dynamic system of fusing and segregating hyphae. Even in a very well balanced heterokaryon, only a fraction of the hyphal tips is heterokaryotic. On a solid surface fungi grow radially and in a vigorously shaken liquid culture as compact spherical colonies. The compact spheres may consist of an aggregation of different mycelia or may contain ungerminated spores. Most yeasts do not have a predominant mycelial growth, although cells may stick together. Growth proceeds by budding (Saccharomyces) or by fission of cells (Schizosaccharomyces). The cells are mostly uninucleate and haploid, but diploid strains do exist. Some fungi are dimorphic—i.e., they can grow yeastlike as well as with hyphae. The best-known example is the smut fungus Ustilago maydis. One form is haploid and unicellular, divides by budding, and is nonpathogenic. The filamentous form is dikaryotic and pathogenic to maize. The yeast form can be grown on synthetic media and is very suitable for genetic studies [4].

Four main groups of fungi are distinguished on basis of the structures for sexual reproduction:

1. Phycomycetes. The sexual spores arise in a sporangium. They may be uninucleate or multinucleate and provided with flagella (e.g., zoospores of Phytophthora) or be nonmotile (Phycomyces). These fungi are in general coenocytic.

2. Ascomycetes. The sexual spores are formed within an ascus. The simplest form is found in yeasts. Two cells fuse and karyogamy is immediately followed by meiosis, resulting in four spores without cell division. Such a cell with four meiotic products is called an ascus. In many Ascomycetes the tetrad cells undergo an additional mitotic division, resulting in eight ascospores having pairwise the same genotype. The yeasts are called hemiascomycetes. The eu-ascomycetes have specialized fruiting bodies (ascocarps) that may contain hundreds to thousands of asci. The main forms are:

Cleistothecium: closed spherical ascocarp (Aspergillus)

Perithecium: a spherical ascocarp with a pore for the release of the spores (Sordaria, Neurospora)

Apothecium: the ascocarp is open at the upper side (Discomycetes as Helotium, Sclerotinia).

In some fungi the ascospores are situated linearly in the ascus. Others have unordered asci.

3. Basidiomycetes. In the Basidiomycetes the generative spores are formed on the meiocyte (basidium). The holobasidiomycetes have an undivided basidium. They are the higher fungi known as mushrooms (Agaricus, Cantharellus etc.). The hemibasidiomycetes have a divided basidium. The main groups are the rusts (Uredinales) and the smut fungi (Ustilaginales).

4. Fungi Imperfecti. This group of fungi consists of fungi of which no sexual stage is known. Most of them are grouped in form genera on the basis of their structures for vegetative reproduction and the form of the vegetative spores. Many Fungi Imperfecti are related to Ascomycetes.

2. GENETIC PROCESSES

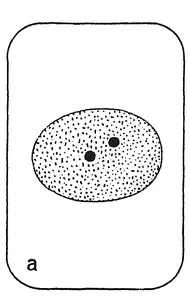

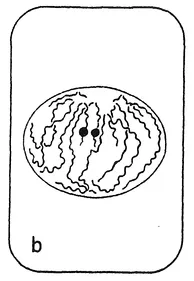

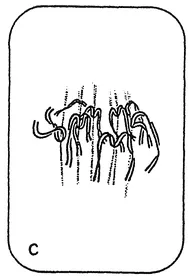

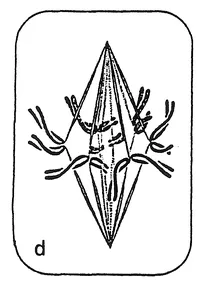

A main point in the life cycle of any organism is the alternation of haploid and diploid "generation." In the diploid phase an organism has two sets of chromosomes (two genomes), and the homologous chromosomes differ when the parents contained different mutations (alleles) on homologous loci. In animals the haploid phase consists only of the gametes, and in higher plants the haploid phase is restricted to few divisions. In lower plants (mosses, ferns) the haploid phase is much longer, and in fact the moss plant is haploid and only the sporangium and the sporangium stalk are diploid. The haploid phase that ultimately produces the gametes is called the gametophyte, and the diploid phase the sporophyte. The phase alternation consists of plasmogamy-karyogarny-meiosis. In both phases the nuclei of the somatic cells divide in a characteristic way (mitosis). In the life cycle only one cell (the meiocyte) has a different nuclear division (meiosis) by which the homologous chromosomes segregate into the daughter cells. Meiosis consists of two divisions (the second resembles a mitotic division) and results in four haploid cells (a tetrad) that can grow out to a gametophyte. The processes are illustrated in Figures 1 and

2. Two different recombination processes occur during meiosis: reassortment of homologous chromosomes, and exchange of genetic materia! between nonsister chromatids of homologous chromosomes (crossing over). The genetic consequences and the use for genetic analysis are discussed in Chapter

3. The organization of the genetic material and the meiotic process are discussed in Chapters 6 and 18.

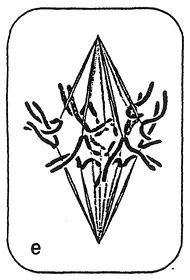

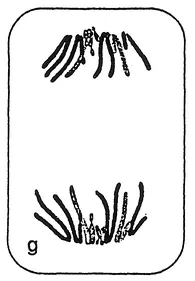

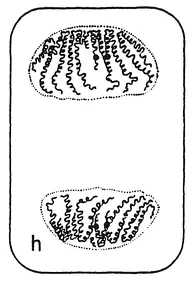

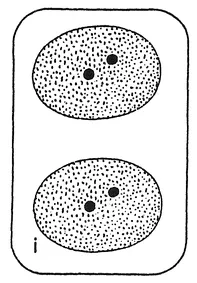

Figure 1 Mitosis in a diploid cell: interphase (a); prophase (b, c); metaphase (d), in which the centromeres are in the equatorial plane due to the forces of the spindle; anaphase (e-g), during which the sister chromatids se...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Contents

- Contributors

- I. GENETIC PRINCIPLES

- II. CASE STUDIES OF GENETIC ANALYSES

- Author Index

- Index of Fungi

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Fungal Genetics by Cees Bos in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.