![]()

1 | LATIN AMERICAN ECONOMIC COOPERATION: CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES OF REGIME COMPLEXITY

Laura Gómez-Mera

The past three decades have witnessed a revival of regional economic cooperation in world politics. Nowhere has this resurgence of regional trade and economic agreements been as dynamic and vigorous as in the Western hemisphere. Since the 1990s, Latin American and Caribbean countries have pursued a multi-tier strategy of trade liberalization, resulting in a complex web of overlapping trade and economic agreements. Moreover, changes in the international economic and domestic political environments in the last decade have led to important transformations in the current landscape of trade relations in the Americas. The ‘open regionalism’ initiatives launched in the early 1990s now coexist with a mosaic of bilateral trade agreements signed with intra- and extra-regional partners. In addition, the last few years have seen the emergence of broader political and economic initiatives that go beyond commercial integration to include cooperation in money, finance, energy and infrastructure.

This chapter addresses two main questions. First, what explains the recent evolution of regional trade and economic cooperation initiatives in the Americas? Why have Latin American countries been so eager to participate in such diverse forms of economic and political collaboration? Secondly, what are the economic and political consequences of the proliferation of overlapping economic agreements in the region? Economists and policy-makers have repeatedly cautioned about the potential economic costs of the emerging ‘spaghetti bowl’ of trade rules and arrangements in the Western hemisphere and beyond (e.g. Bhagwati 2008). Less attention has been paid to the international and domestic political impact of this increasing regime complexity characterizing regional economic relations in the Americas. In what ways has the increasing density of regional agreements affected the strategies and decision-making processes in Latin American countries? More importantly, have institutional proliferation and overlap worked to facilitate or to undermine regional unity and collaboration efforts?

The chapter is organized as follows. The next section briefly describes the evolution of regional economic cooperation attempts in the Americas since the early 1990s. I show that the current landscape of regional economic cooperation in the Western hemisphere is characterized by increasing complexity and overlap of different types of trade and economic agreements. The following section seeks to account for this increasing regime complexity, considering the role of global economic pressures, power asymmetries and domestic political factors. In the fourth section, I focus on the consequences of the overlap of competing and complementary trade and economic commitments in the Americas. In the conclusion, I summarize the main arguments and discuss their implications for the longer-term evolution of South–South cooperation in the Americas.

The changing landscape of regional trade and economic cooperation in the Americas

Regionalism has a long history in the Americas. Indeed, as early as the 1820s, Latin American countries sought to strengthen regional ties through the creation of regional institutions. Building on the Bolivarian ideal of hemispheric unity, the Organization of American States was created in 1948. In the 1950s and 1960s, countries in the region pursued regional economic integration in support of the prevailing development strategy of import substitution (Devlin and Ffrench-Davis 1998). The Latin American Free Trade Association, the Andean Pact and the Caribbean Free Trade Association date from this period. Despite their ambitious objectives, these initiatives had limited results, falling short of the objective of promoting regional interdependence and economic growth.

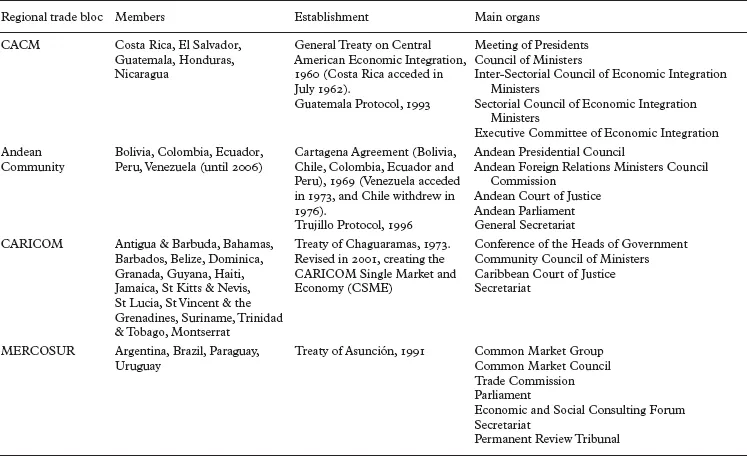

The late 1980s and early 1990s witnessed a resurgence of efforts at regional economic integration triggered by a combination of security, domestic political and economic considerations. In the early and mid-1990s, countries in the region signed a series of preferential or ‘economic complementation’ agreements (ECAs) within the framework of the Latin American Integration Association (ALADI). Four aspiring common markets or economic communities were also created during this period: the Southern Cone Common Market (MERCOSUR), the Andean Community of Nations (ACN), the Central American Common Market (CACM) and the Caribbean Common Market (CARICOM). The creation of a customs union – a free trade area with a common external tariff vis-à-vis imports from third countries – was thus a necessary step in that direction. However, the four Latin American regional groupings established in the 1990s have made limited progress in this direction, and continue to be characterized by important imperfections and perforations in their common external tariffs.1

The revival of regional cooperation in the 1990s was initially welcomed in policy-making and academic circles (IDB 2002). In particular, analysts emphasized the differences between this new wave of ‘open’ regionalism and the inward-oriented regional integration projects of the 1950s and 1960s (Devlin and Estevadeordal 2001). As a report by the Inter-American Development Bank put it, ‘[t]he new regionalism is an integral part of an overall, structural policy shift in Latin America toward more open, market-based economies operating in a democratic setting’ (ibid.: 3). The strategy of regional trade liberalization, pursued in tandem with unilateral and multilateral opening, resulted in an unprecedented expansion in intra-regional trade levels. This initial success seemed to lend credence to the early optimistic assessments of the ‘new regionalism’.

TABLE 1.1 The ‘new regionalism’ in the Americas

However, towards the end of the 1990s, the Latin American subregional trade blocs seemed to be running out of steam. Much like their predecessors, the new regional integration agreements confronted serious implementation and compliance problems. Moreover, the deterioration of international economic conditions in the late 1990s severely disrupted trade relations among Latin American countries. Domestic macroeconomic and political instability in several South American countries further depressed trade levels within MERCOSUR and the Andean Community (Rosales 2009). The early 2000s also witnessed gradual but progressive stagnation in the process of hemispheric trade cooperation, including the suspension and eventual termination of Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) negotiations.

The collapse of the FTAA, when combined with the stalemate in multilateral trade negotiations and the growing disillusion with neoliberal reforms throughout Latin America, significantly affected patterns of regional economic cooperation in the Western hemisphere in the 2000s. In fact, these important changes at the international, regional and domestic levels contributed to the emergence of two distinct – but coexisting – new models of trade and economic agreements in the region: (i) the rise and proliferation of bilateral trade agreements with intra- and extra-regional partners; and (ii) the emergence of the broader projects of ‘post-liberal’ regionalism that seek to go beyond trade to include cooperation in monetary, financial, energy and other noncommercial issues (Da Motta Veiga and Rios 2007). These two new strategies of regionalism have evolved side by side with the customs unions and deeper integration agreements created in the 1990s, thus resulting in an increasingly complex mosaic of overlapping institutions.

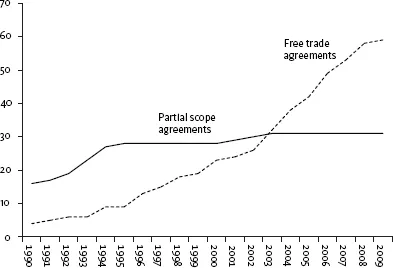

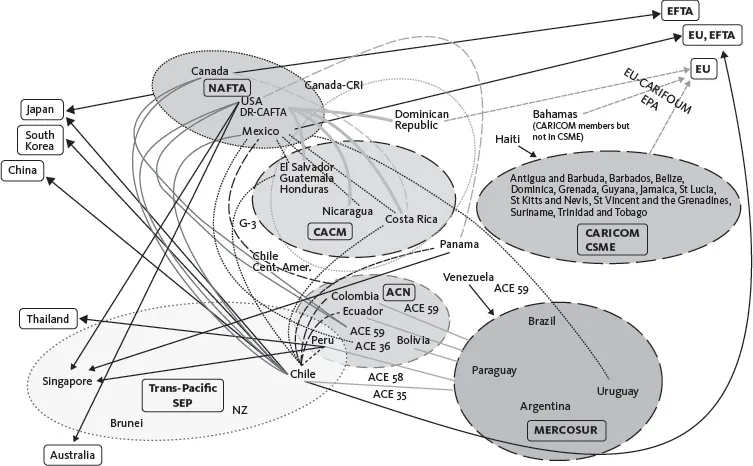

Proliferation of overlapping preferential trade agreements Some Latin American countries – most notably Chile and Mexico – began relying on bilateral trade agreements with intra- and extra-regional partners in the second half of the 1990s. However, as Figure 1.1 illustrates, the number of bilateral preferential trade agreements (PTAs) signed by Latin American countries experienced a dramatic surge after 2003. Frustration with the slow pace and eventual breakdown of the FTAA negotiations in the early 2000s led the USA to negotiate separate agreements with ‘can-do’ countries, which were prepared to undertake regulatory reforms in exchange for preferential access to the US market (Shadlen 2008; Quiliconi and Wise 2009; Phillips 2010). Between 2004 and 2007, the USA concluded agreements with Chile, Central America and the Dominican Republic, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and the Caribbean countries. Also during this period, Latin American countries expanded their web of bilateral links. An agreement between Chile and Central American countries came into effect in 2002. Most notably, after long and protracted negotiations, an ‘economic complementarity agreement’ was signed in 2004 between MERCOSUR and the Andean Community.

1.1 Number of RTAs in effect by year (total) (source: SICE)

Another novel feature of the more recent landscape of trade agreements in the Western hemisphere is that the rise of intra-regional bilateral trade agreements has been complemented by an accelerating trend of South–South ‘transcontinentalism’ (Estevadeordal and Suominen 2009). Mexico and Chile are leaders in this respect, signing free trade agreements with developing and emerging countries all over the world. Since then, Chile has entered agreements with Korea (2004), China (2006), New Zealand, Singapore and Brunei (2006), Japan (2007) and Australia (2008). Mexico, in turn, has concluded negotiations with Israel (2000) and Japan (2004). Peru has also been active on this front, recently establishing regional trade arrangements (RTAs) with Thailand (2005), China (2009) and Singapore (2008). Although some of this activity was definitively North–South in character, South–South arrangements are also increasing. In 2004, MERCOSUR signed a preferential agreement with the Southern African Customs Union (SACU). The South American bloc also has agreements with India (2004) and Israel (2007).

The rapid spread of bilateral deals has undoubtedly increased the complexity of the spaghetti bowl of regional trade agreements in the Western hemisphere (see Figure 2.1). This growing institutional density has been exacerbated by the emergence of a new type of regional integration project, which has broadened the scope and nature of the commitments undertaken by Latin American countries.

1.2 Spaghetti bowl of PTAs in the Western hemisphere (source: Baldwin 2008)

‘Post-liberal’ regionalisms A second model of regional cooperation initiatives that has recently emerged in Latin America further adds to this complex landscape. As some scholars have noted, the emergence of these ‘post-liberal’ projects, such as the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (ALBA) and the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR),...